Desert scenes of an army’s destruction fill an entire gallery, from floor to ceiling. The view switches between shots taken from an aircraft – bomb craters, fields of shattered armour and abandoned trenches already softened by erosion and sandstorms – and others taken at the photographer’s feet: sacking, boots, looted goods and shell cases. The photographs in Sophie Ristelhueber’s Fait were taken seven months after the Gulf War. The piece documents the exemplary destruction of the Iraqi army, and the deaths of a quarter of a million conscripted soldiers, in a campaign from which reporters and photographers were largely banned. Yet the alternation between pictures in colour and monochrome, the sheer size of the installation – which could only be displayed in a gallery or museum – and the oscillation in scale (is that the remains of a trench or a line drawn with a finger in the sand?) make it clear that Fait does not simply substitute for the images that censorship prevented coming into existence. The destruction, here, is both vast and personal, and is held in tension with the desire to see the ruination of power.

Fait is showing as part of Conflict, Time, Photography at Tate Modern (until 15 March). One image in particular stands for the concerns of the exhibition as a whole: a tank, blown onto its side, with the turret upended nearby, looks uncannily like an SLR camera body with the lens removed. Such strange affinities between photography and the effects of conflict recur throughout the show, in which photographs are grouped according to how long after the conflict (or event) they were taken. In the first rooms, the interval is moments, and photojournalism makes a brief and slight appearance. But as the interval extends to weeks, months, years and decades, the relation between image and event becomes less and less immediate, and the last rooms dwell on what can no longer be seen.

This organising principle is a clever solution to the difficulty of making a display about war and photography that isn’t the usual historical run-through. A recent show at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts focused on persistent genres in war photography, such as embarkation, encampment, death and mourning. The result was a flattened view that made all wars look alike; it also seemed to want to educate the public in the worldview of the armed forces and to proclaim the glories of American power. The Tate exhibition is mercifully free from celebration of empire. Its tone is rather mournful and its presiding spirits (or spectres) are not military but literary: Duras, Ballard, Virilio and above all Vonnegut. There are quotations from Vonnegut on the wall outside the show’s entrance, a copy of Slaughterhouse 5 is displayed in the first room, and Richard Peter’s photograph of a statue overlooking the firebombed cityscape of Dresden is on the front cover of the catalogue. All these authors explore the effects of conflict on the perception of time and, like photographers, play with the concatenation of temporal frames.

Even so, one of the quotations outside the exhibition picks out the moment in Slaughterhouse 5 when the narrator is told that writing an anti-war book is like writing an anti-glacier book: ‘What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that too.’ Here war is eternal and immutable, and while it should not be glorified, perhaps we are stuck with its trauma, with grieving and, at a greater distance, with melancholy for all that has been lost.

The photojournalism in the first room is the work of a single figure, Don McCullin. His portrait of a Marine fresh from intense fighting for Hue in the Tet Offensive has been elevated by its fame from photojournalism to the realm of high art, and considerable skill has gone into enlarging it from a 35mm negative into a tableau photograph. (One of the strengths of the exhibition is to show a great deal of contrasting art photography – by Luc Delahaye, Agata Madejska, Simon Norfolk, Stephen Shore, Shomei Tomatsu, Jane and Louise Wilson and many others – in skilful juxtaposition.) McCullin reappears later in the show, this time photographing in Berlin in 1961 as the Wall is erected: curious US troops peer over the new barrier. This sequence is labelled ‘16 Years Later’, as though McCullin were photographing, not his actual subject, but the echoes of the Second World War. This would doubtless have come as a surprise to him. One problem posed by the show’s conceit, perhaps not intentionally, is the difficulty of knowing which event should be used to set the clock. Sometimes it is an explosion (as in the remarkable photograph by Luc Delahaye of dust thrown up by an IED attack in Ramadi), sometimes a crime or an execution, and sometimes an entire war. And wars can have uncertain, blurry endings, as Jim Goldberg’s work about those seeking to flee the Congo makes clear. Perhaps this is one reason Hiroshima and Nagasaki are given such prominence in the exhibition: these colossal events can be timed to the second, stopped clocks and watches, and began with a blinding flash.

The other difficulty for the show’s conceit is that most photographs taken in uncontrolled conditions, and particularly in urban spaces, contain numerous time-frames – old buildings and new, weathering, shadows that track the time of day, the frozen movements of people and things. Many potential points of origin are in the frame. Yes, Michael Schmidt’s eloquent and understated city scenes, Berlin nach 45, show the empty spaces left by the destruction of the city in the Second World War. But there is just as much that points to different origins: the erasure of war’s traces and wounds, for instance, in the modern uniformity of concrete blocks and car parks.

At an extreme, depictions of loss and ruination can appear as sublime visions of ever increasing entropy, of which war is just one agent. Yet there are elements in this exhibition which point to a more specific and political view, and to changes in the nature of war and attitudes to it. The wall-sized introductory text in the first room, its typography suggestive of Constructivist propaganda, notes that Vonnegut signed off his texts and essays with the word peace. The word is enlarged and written in red. In the last room, there is a prominent series of landscapes by Chloe Dewe Mathews in which she revisits places where soldiers were executed for desertion or cowardice in the First World War and photographs the scene at the time and day of the shooting, 99 years later. We do not, of course, see what the executioners and their victims saw: sometimes the view is dominated by young trees. But all that is unseen provokes the viewer’s imagination. It is a forceful statement to begin with ‘peace’ and to end with scenes that recall the lethal enforcement of what is often called heroism.

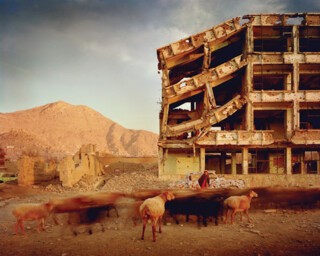

And there is a broader point. In an earlier room, tourists’ photographs of the ruins of France after the First World War are shown opposite similar photographs of ruins in Afghanistan by Simon Norfolk. The French pictures were once seen as an affront to the dignity of the nation and as evidence of German moral deficiency. It is impossible to read Norfolk’s work in anything like the same way: his devastated landscapes are the product of decades of futile warfare; these pictures issue into a world in which war has been in long decline. Yet as we have become more anti-war, we have also become more ‘anti-glacier’. It adds a different complexion to the melancholy of the exhibition that our increasing pacificity is likely to be undermined by environmental devastation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.