I first went to Camberwell New Cemetery about six years ago, looking for the grave of a young man called Melvin Bryan, a petty criminal who died after being stabbed at a drug-house in Edmonton. Walking down the pathways and over the crisp, frozen leaves, I’d noticed how many of the people buried there had died young – you can often pick them out by the soft toys resting against the gravestones. Last winter I came back to the same place. It was even colder this time, and the pathways were glittering as I made my way down to the church. I hadn’t taken in before that Charlie Richardson, leader of the Richardson Gang, was buried here, as well as George Cornell, the gangster shot by the Kray Twins in The Blind Beggar pub. But it was the graves and sentry toys of the unknown children that had lodged in my mind. The trees were bare, filtering light on the tombstones and pointing down at the stories gathered there. When I say ‘stories’, I don’t only mean the ones clinging to the gravestones, but the stories you come with, the tales you tell yourself and that don’t yet have a particular meaning. For some reason not yet clear to me, I noted down the names of Paul Ives, Graham Paine (‘who lost his life by drowning’), Clifford John Dunn, Ronald Alexander Pinn and John Hill, all of whom were born in the 1960s, as I was, and died early.

The practice of using dead children’s identities began in the Metropolitan Police Force in the 1960s. Until very recently, it was thought, in-house, to be a legitimate part of an undercover officer’s tradecraft. It involved taking a child’s name from a gravestone or a register and building what the police called a ‘legend’ around it. When I first heard about it, I wondered if the officers involved in this activity were not in fact covert novelists, giving their ‘characters’ a hinterland that suited the purpose of their present investigations, as well as a false passport and a new face. The Met officers, without informing the families of the children, and using their original birth certificates, built a profile for themselves that would pass for an actual person. And as such – as actual people – these policemen infiltrated left-wing groups posing as activists. In 2013 several officers who had worked for the Met’s Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), including a Sergeant John Dines, admitted using the identities of dead children to conceal their own identity. Dines took the name of John Barker, who died of leukaemia in 1968, at the age of eight. In several of the cases, officers kept their fake identities for more than ten years and exploited them in sexual situations. To strengthen their ‘backstory’, they would visit the places of their ‘childhood’, walking around the houses they had lived in before they died, all the better to implant the legend of their second life.

Mick Creedon, chief constable of Derbyshire, reporting last year as part of Operation Herne, stated that 106 covert identities had been ‘identified as having been used by the SDS between 1968 and 2008’, and confirmed that many of those identities had been ‘fictitious’. For reasons of ‘operational security’, the chief constable would not confirm or deny the names of specific dead children or specific police officers. There was no moral questioning. The report was forced into existence by bad press, and, though it made apologies, we were left with no real sense of what exactly had been done. The situation said a lot about the power of the police and the power of the media to move the police to apology. Yet the story went deeper than that. What was it to live a second life? What was it to use a person’s identity – and did anyone own it in the first place? Is it the spirit of the present age, that in the miasma of social media everyone’s ‘truth’ is exploitable, especially by themselves? Is the line between the real and the fictional fixed, and could I cross the line of my own inquiry and do the police in different voices? Could I take a dead young man’s name and see how far I could go in animating a fake life for him? How wrong would it be to go on such a journey and do what these men had done? I chose to get at the conundrum by pursuing Ronald Pinn into the fantastical dimensions of a future life he didn’t live. If the task ahead turned on an outrageous defilement of a person’s identity, then that, too, would be part of the story I was trying to tell. But the costs were real. An immersion in wrongdoing and illegality would be necessary to tell it from the absolute centre.

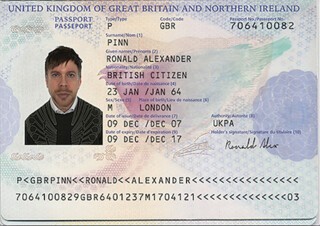

Ronald Alexander Pinn

‘Ronnie’

DIED 9.8.1984

Aged 20 years.

My happy handsome son,

I pray for the day when we meet again,

All my love, Mum.

I had no idea as I left East Dulwich that evening how far beyond the police’s bad behaviour the story would go; that it would be about the ghostliness of the internet and the way we live with it. But I remember putting on my car headlamps and watching the yellow light pick out the graves, and I stayed there for a while thinking about the fictions I had grown up with.

The real Ronald Pinn was born on 23 January 1964. His mother’s name was Glenys Lilian Evans and she came from the area around the Old Kent Road. His father grew up in the same part of London and was working as a builder when Ronnie was born. In that year, they lived at 183 St James’s Road in Bermondsey. British Pathé footage shot on the Old Kent Road during the 1970s shows children on the streets, and early in my search, I used to scan the little groups playing by building sites or standing at bus stops, the children under the advertising hoardings or walking past the shops, to see if any of them resembled a blond-haired boy in a photo on a family tree, a boy that a family research website told me was Ronnie Pinn.

That photo was the only evidence of Ronald Pinn’s existence in the public domain: a blurred and fuzzy image of a person whom hardly anyone still remembered. As far as the internet was concerned, Ronald Pinn had never existed, and neither had any of his family. There were no reports, nothing from any newspapers, no certificates, no records and no social media footprint to measure. Just this single, blurred photo. I began to wonder if paperwork or old-fashioned memory might have preserved what the internet disdained, but everyday material that hasn’t been digitised and has no fame value is increasingly hard to find. I wrote to all the people in all the school classes that might have been attended by Ronnie Pinn. I wrote to all the Pinns in London. And only slowly did one or two emerge from the non-digital ether, the old-fashioned air, to tell me what they remembered of him. His family had lived in Avondale Square, just off the Old Kent Road, and I went to see the tired old flats down there. I could see him playing on the grassy mound in the hot summer of 1976 when he was 12. I could see him shouting up to his mother standing on the balcony and parking his Chopper by the trees under the flats. And often I realised it wasn’t Ronnie I was seeing: I was seeing myself, a boy of similar age who somehow knew those places well, and hung about in the unrecorded life.

Ronnie went to Sir John Cass’s Foundation Primary School, a Church of England school not far from the Tower of London, but nobody remembers him there. I saw some photographs of boys on an outing to Stonehenge; it was the right period, but Ronnie wasn’t pictured. Pupils remembered other people and they remembered the school’s routines, like walking in twos to St Bodolph’s in Aldgate to take part in church services. Ronnie’s mother hadn’t liked the look of the primary school near where they were living, so he made the journey each day to Sir John Cass’s, and he was happy there if not commemorated in any way. Former pupils at Bacon’s Secondary School in Bermondsey still talk about the famous people who went there, but nobody noticed that, after primary school, Ronnie Pinn was there too, until 1980. In my hunt for the real Ronnie, I thought several times that I saw him in grainy photos posted by ex-pupils on Friends Reunited. Was he not the boy in the white shirt at the edge of a photograph taken in front of the school in 1980, with kids tumbling over each other and somebody spraying from a shook-up can?

He tended to do well in class but on a report card for July 1978 you can see things were changing. His attendance was dropping and he had four detentions. He got an A in Maths and Drama, but did less well in English and got a D in French (‘Ronald made very little progress this year’). He got an A in Metalwork, but the teacher couldn’t think of his name and wrote ‘Robert’ while telling him to keep up the good work. His form teacher, Mr Norman, said that ‘Ronnie’s attitude and standard of work is slipping. I hope that he takes note of what has been said to him recently. He is always pleasant and happy.’ Ronnie seemed like a person ready for the world outside and he left school as soon as he was allowed to. Someone remembered him on a trip to Wales. ‘Ronnie said he was in the dorm when a little boy came and sat on the end of his bed in the middle of the night, a boy dressed in old-fashioned clothes. Then he disappeared.’ The person who told me this then sighed. ‘I think Ronnie was born to die. I mean, we all are, but him especially.’

Ronnie met a girl, Nicola Searle, whose family worked the market stalls just outside London, and he started working with them. That was his life for a time, a certain amount of ducking and diving in the stallholders’ world. Eventually he bought a Golf soft-top car and he idolised it. He wasn’t ambitious. He went on nights out and he bought some suits and took the occasional line of cocaine. It was the early 1980s and boys like Ronnie were popping up in the City and making new selves for themselves. But Ronnie seemed happy to stick with the same small group of friends in South London. Some time in 1983, his girlfriend broke with him and took up with a guy they both knew called Coxy. Ronnie couldn’t understand it – the guy turned out to be no good – but he found another girl, Sharon, ‘a girl with legs up to here’, he said, and people insist he would have married her. The break-up was awkward because he was still living in a flat he’d leased from Nicola’s family, high up in a block in Cotton Gardens, halfway down Kennington Lane.

It was a Thursday, the day he died. He had a habit of ringing his mother every day but she hadn’t heard from him that week. She went looking for him, and, after asking around, found his car in a side street off the Tower Bridge Road. She couldn’t understand why he would leave his car there and she went in search of him. At a pub near Avondale Square she met a friend of Ronnie’s called David. He said he’d been with Ronnie the day before and that Ronnie was in bed the last time he saw him. (The coroner would later describe this man as an ‘unsavoury witness’ without detailing why.) Mrs Pinn, in company with another boy from the bar, went to the block of flats where Ronnie lived. She was nervous going up there because it just wasn’t Ronnie to let days go by without ringing her to say hello, and her panic increased when they discovered his flat was locked from the inside. The caretaker and the young friend went to find another way in while Mrs Pinn sat in a neighbour’s flat. When I first learned of the basic circumstances of Ronnie Pinn’s death, I didn’t know if his mother was alive. I was still looking through electoral rolls and writing letters to people who weren’t her. She never believed Ronnie was a heroin addict. Was the heroin dose that killed him part of a life she didn’t know about?

Inside the flat, Ronnie’s trousers were folded over a chair by the bed. An alarm call had been set on the phone right next to him. And his passport was there, showing stamps from a visit to Santiago de Compostela and a trip to America he’d made with an uncle when he was young. Everything was in its place in the flat. Ronnie lay dead, aged twenty, with nothing around him and few records attached to his name. He was gone. He had died not three miles from where he grew up, and, in the three decades to come, his name crossed only once onto the internet, attached to that photograph of a boy on a distant family tree. I went to meet a man at King’s Cross Station who had gone to school with one of Ronnie’s uncles. He showed me a picture and I could see the family resemblance, but the man couldn’t remember Ronnie. And hardly anyone he went to school with could recall him either. In 2014, none of them knew that the remains of Ronald Pinn had lain in a cemetery in Camberwell for three decades. They all had children of their own and houses on which the mortgage was almost paid. They had reunions to attend and they would reminisce on ancestry websites about housing estates now swept away, about buses that no longer ran and music they’d forever associate with other lost boys.

My first step in trying to create a fake identity based on Ronald Pinn’s was to apply for the real Ronnie’s death and birth certificates. This is why the police and others use real young people who died: like the rest of us they have certificates that can form the basis of a credible story, but in their case there isn’t a continuing life, or much life at all, to get in the way of the made-up story. I didn’t know Ronnie’s mother’s maiden name at the time but I fudged that and easily got the certificates from the General Register Office. As in every case, the certificates begin a process of legitimisation: if you have a birth certificate you can get other documents, and in this way a fake identity’s ‘legend’ is grounded. The real Ronnie’s family background wasn’t hard to establish from the certificates: his father died in 1997; his paternal grandfather, Alfred E. Pinn of Southwark, was born in 1908; his great-grandfather, a trader called Zenos Thomas Victor Pinn, died in Lambeth Hospital during the Second World War. On the one hand, people are obsessed with ancestry and stories of origin, and records that used to take weeks to search are now visible in a matter of minutes, for a fee. On the other hand, Facebook and other social media platforms encourage the opposite: the invented life. Writing this story, I moved continually from one way of knowing a person to another, from the real to the fictive, and it seemed a pretty contemporary way of understanding a life.

The day after I went to see the house the real Ronnie grew up in, the 1930s block in Avondale Square with grass at the front and children playing outside, I invented a real email address for my fake Ronnie. Fictional characters have a habit of gathering material to themselves, and so it was with my invented Ronnie. I began to establish a background for him, a legend that touched on my own, while at the same time leaving the original Ronnie behind and forging new connections to a plausible self. I decided his family’s address at the time of his birth would be 167 Caledonian Road, because the address seemed right in class terms for the man I was inventing and also because I have a feeling for King’s Cross. I placed him at Blessed Sacrament Catholic Primary School in Boadicea Street, which, after visiting it, I gathered would have been a new school when ‘Ronnie’ attended. Like a spy, I wanted my character to have a legend that was so copper-bottomed, so strong and sure, like Oliver Twist’s, say, or Humbert Humbert’s, or mine, that it wouldn’t just fool the public but very nearly fool its author. I looked at old photographs from this school, and from the secondary school I placed him at, St Aloysius College in Highgate, and inserted him in group photographs from the 1970s, after St Aloysius became a comprehensive. I matched his dates to real people who would have been at the school during those years, and saw that his first friends could have been Paul Ward, Brian Foster and Terry Klepka.

Many of our modern crimes are crimes of the imagination. We think of the unspeakable and exchange information on it. We commit a ‘thought-crime’ – giving the illicit or the abominable an audience. Some of us pretend to have relationships we don’t actually have just for the sense of freedom it gives us, and some want porn for that reason too. Building the fake Ronnie became something more than creating a character in a novel: it became personal, like living another life, as an actor might, trying not only to imitate the experience of a possible person but to test the meaning and limits of empathy. I decided my Ronnie, unlike the real one, would have gone to university and I placed him at Edinburgh from 1982 to 1986. I applied for a fake degree certificate in his name – there are several websites offering this service, all of them pretending the certificates are for ‘novelty value only’, but they look as real as the originals, have identical seals, holograms and watermarks, and can sell for thousands of pounds. They are clearly meant for people who want to pretend they have a degree that they don’t have. Edinburgh seemed right: I knew how to think as Ronnie in the Edinburgh of those years.

I realised my Ronnie would need a face. He would need it more for identity cards than for his online life, though even there it seems wrong after a while not to have a face to represent the self you are projecting to the world. I could have lifted an age-appropriate face – the chances of detection would have been slight. But I was uneasy about that: I suspected my Ronnie might travel into some dark areas, and I wanted it to be me who was to blame, or at least responsible, so the face of a real person, alive or dead, was out. Through a friend in the film business, I contacted a special effects guy and over tea in Portland Place I swore him to secrecy. The conversation about how my man would look turned into something like a casting session. ‘I think he should look like me, but not too much,’ I told him, and we agreed he’d make several portraits of a face that blended mine with those of two other men who agreed to sit for portraits. Ronnie’s face would then be a blend of the three. My special effects helper asked me if I’d heard of Weavrs.

‘What’s that?’

‘It’s where you’re going,’ he said. According to their website, Weavrs are ‘personality-based social-web robots’ that ‘publicly blog about how they feel, where they go and what they experience’. An article by Olivia Solon in Wired magazine questioned the guys behind it. ‘The team … won’t reveal exactly how the Weavrs algorithm works – referring to it as their black box,’ Solon wrote, ‘but say they create personalities from social data that then “blog themselves into existence”.’ It’s taken for granted in these circles that digital robots are becoming a tool of big business; in China, for instance, Weavrs are used to collect data on young people and their preferences. In the old days researchers would speak to individuals, but nowadays the invented person, the digividual, is more reliable when it comes to showing what people want.

The unstable factor is ‘people’. My Ronnie Pinn had integrity at his source, a real person who lived and breathed and was called Ronnie Pinn, but he himelf had none, which didn’t stop him from beginning to live a life much larger than reality. The photograph of ‘Ronnie’ showed a man in his forties with his author’s eyes and a younger man’s haircut. He was a composite yet he seemed quite ordinary – everyone, after all, is a composite – and nothing about him suggested he wasn’t walking in the world like us. My Ronnie was soon set up on Facebook, with his photo uploaded and his background details included, his ‘education’, his football team (West Ham), and the fact that he now worked as a driver for a firm called Executive Cars. It was at this point that Ronnie’s ‘character’ began to veer off on its own, as characters do when you’re creating them in fiction. Ronnie, it turned out, was quite right wing, he was gay, he was a historian who’d turned his back on academia and wanted England out of Europe. On Facebook, he expressed his character in his choice of people and institutions to follow. He liked fast food, so, for a while, he had a logo of Wendy’s Burgers on his page. He had Wembley Stadium as the background on his home page. Every day I added new elements to him and found new avenues. He liked Star Trek, The Wire and Queer as Folk. He joined Twitter and started following certain monarchists, capitalists, fast food outlets and old school connections, as well as politicians like Nigel Farage. People automatically started following Ronnie Pinn, either because of his interests or because he followed them. But to increase his footprint I kept adding more possibilities, including a host of fake Facebook friends. They were like ghosts and I came to think of them as figments, the invented, the others, who shored up the legend of a fake person by being plausibly real while being totally fake. In less than an hour one morning the invented friends of Ronnie Pinn came into being. They had names like William Eliot, Jane Deleon and Stephen Watley, and who’s to say they weren’t ‘real’. After a while, an alarm bell went off somewhere, and Facebook sent a warning. ‘Please verify your identity,’ it said. ‘Facebook does not allow accounts that: Pretend to be someone else; Use a fake name; Don’t represent a real person.’ But the fakery of the fake Ronnie’s fake friends didn’t trouble them for long. It was just another robot sending the warning, moved to do so after a number of keystrokes set off the alarm. But the fakery continued to go deeper and Ronnie Pinn grew in reality and the warnings disappeared. Facebook has 864 million daily users, of whom at least 67 million are believed by the company to be fake. There are more social media ghosts, more people being second people, or living an invented life as doppelgängers, than there are citizens of the UK.

In many ways my Ronnie was a typical 21st-century citizen. Not least in his falseness. Valuable fake identities are being constructed and deployed in every area of life, and often they are simulacra of their maker’s own identity. It emerged last year, in a book called Murdoch’s World by David Folkenflik, that public relations staffers at Fox News Channel were serially creating dummy accounts to plant ‘Fox-friendly’ reactions to critical blog postings. One ex-staffer spoke of more than a hundred false accounts set up for this purpose, and said they’d covered their tracks by the use of different computers and untraceable broadband connections. Far from being the creations of stoned computer nerds, fake online identities had long since become a standard feature of big business espionage, police investigations, government surveillance, marketing and public relations. Democracy itself – with its basic notion of one individual and one vote – is far from being an innocent notion in the age of ‘astroturfing’, when whole movements of opinion can be manufactured in an instant, drummed up by the keyboard-savvy, who harvest ‘names’ from social media to support their cause or denounce someone else’s. Edward Snowden opened a door on state-sponsored snooping on private lives, but also, more subtly, he revealed the many ways private life has given itself over to the dark arts of fabrication. A dirty tricks document produced by a secret unit at GCHQ called JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group) was called ‘The Art of Deception: Training for a New Generation of Online Covert Operations’. JTRIG described itself as ‘using online techniques to make something happen in the real or the cyber world’. Making ‘something happen’ very often means invading someone’s Facebook account and changing the photographs, or mobilising the social network to ridicule them. A ‘fake flag operation’ for example involves posting material on the internet under a false identity with the aim of damaging a reputation. The damage comes under one of two headings: ‘Dissimulation – Hide the Real’ and ‘Simulation – Show the False’. In other words, exploit the porousness of the border between the real and the imagined, as if some Borgesian nightmare had taken over, feasting on a general uncertainty about who exists and who doesn’t. The world, according to GCHQ (and not only GCHQ), is now a zone of conjuring. ‘We want to build Cyber Magicians,’ the secret report tells its secret readers.

Stories of people pretending to be other people, of people feeling impelled to confect, imitate or perform themselves, describe a change not just in the technological basis of our lives but in the narrative strategies now available to us. You could say that every ambitious person needs a legend to deepen their own. Last year Manti Te’o, an exceptional Hawaiian linebacker, a Mormon who played for Notre Dame, found his when he told the sad story of having to succeed for his team after his 22-year-old girlfriend, Lennay Kekua, died of leukaemia. Despite his grief, the footballer stormed up the field, making 12 tackles in one game, before appearing on news programmes to talk about his heartbreak and to quote from the letters Lennay had written him during her terrible illness. Problem was: the girlfriend never existed. She was a complete invention – the photographs on social media sites were of a girl he’d never met. He’d missed Lennay’s funeral, Te’o said, because she insisted that he not miss the game. There are hundreds of stories like this, where ‘sock-puppet’ accounts on Facebook and elsewhere have allowed a ‘person’ – sometimes a whole ‘family’ – to put together a life that’s much bigger than the real one. The Dirr family from Ohio solicited sympathy and dollars for years after losing loved ones to cancer – a small village of more than seventy invented profiles shored up the lie. It was all the work of a 22-year-old medical student, Emily Dirr, who’d been inventing her world since she was 11. Her life was a reality show that she produced, cast, directed, starred in, and broadcast to the world under a pile of aliases that felt entirely real and moving to a large group of devoted followers.

By the middle of last summer, Ronnie Pinn had a Gmail account and an aol account, as well as accounts on Craigslist and Reddit. It took the best part of a week to install and run the software necessary to get the bitcoins he needed to confirm his existence. I bought them with a credit card – hundreds of pounds’ worth – on computers that couldn’t be traced back to me. In each case they had to be ‘mixed’, or laundered, before Ronnie could buy things. Around every corner on the web is a scam, and the Ronnie I invented had to negotiate with some of the dodgiest parts of the World Wide Web. He now had currency; next he got a fake address. I used an empty flat in Islington, where I would go to collect his mail, the emptiness of the hall seeming all the emptier for the pile of mail on the floor, addressed to someone who didn’t exist but was more demanding than many who did.

It wasn’t long before I saw Ronnie’s face on a driving licence. It took a few weeks to secure a passport. The seller was on the dark net website Evolution; having gathered all ‘Ronnie’s’ information, he produced scans on which the photographs were missing. Then he disappeared. This is common enough: the sellers no less often than those seeking to buy their wares are crooks. Another seller produced the documents quite quickly and with everything in place anyone could have been fooled. Not perhaps the e-passport gates at Heathrow, but a British passport is a gateway ID to many other forms of ID, as well as to a world of legitimacy. Slowly and digitally, ‘Ronnie’ began to be a man who had everything, a face, an address, a passport, discount cards. He began to have conversations with real people on Reddit, or people who might have been real, and his Twitter and Facebook life showed him to be a creature of enthusiasm and prejudice. Nowadays, everyone can be Frankenstein and his monster, both the hare-brained dreamer and his gothic offspring, and the enabling technology seems to encourage the idea. Ronnie, in the world, was a figment, but on discussion boards he was no less believable than anybody else. ‘Friend’ has become a verb, leaving the old world of ‘befriend’ to hint at warm handshakes and eyes that actually met. People ‘friend’ people on Facebook and they get ‘friended’, but many of them will never meet. Elsewhere on the net the connections may lead to a cold presence, a person who is legitimate but non-existent. Ronnie’s social interaction online could be involved and energetic and characterful, but it seemed that everyone he met had a self to hide and nothing to show for themselves beyond their quips and departures. At one point, Ronnie’s Twitter account got hacked and he was invaded by hundreds of robotic right-wing followers. His ‘information’ had opened him up to being exploited by spam-bots, by other machines, and by web detritus that clings to entities like Ronnie as a matter of digital course. None of these everyday spooks came in from the cold, and Ronnie moved, as if by osmosis, into the more criminal parts of the internet, where the clandestine earns its keep.

It wasn’t a million years ago that Marshall McLuhan was able to imagine the media as the benign source of a new togetherness: a place where ‘psychic communal integration’ might occur. But our experience of the internet is tangled with our sense of what its abusers are making of it. The technology is now a surveillance machine, a lying tool, a handheld marketing device, a corporate pinboard, a global platform for ideologues and zealots, as well as a handy life-enhancer. If Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the rest bring people together, they also complicate our notion of what a person is, and it’s very different from former notions of reality and privacy. After several months, Ronnie had begun to press himself into some officially sanctioned world of paperwork, and, though the paperwork was false, his online demeanour suggested a reality as big as anyone’s. The Ronald Pinn I created from the distant memory of a young man in a graveyard became, in imitation of the bent police officers who inspired his creation, an illegal alien in a world of bespoke reality. The police officers, under their new identities, had affairs and fathered children before disappearing home to their real lives and the world that squared with who they were. Ronnie Pinn had only one direction to go in, down and down into a world of seeming freedom, the dark web, where one can be anybody one wants to be, and at a happy advantage if ‘invented’. The dark web is a place where rules can’t be dictated by any external authority, a place that laughs at authority and authenticity. Normal search engines can’t reach it and access can’t easily be traced to anyone’s computer. Ronnie found his natural domain in that world of few-questions-asked, though I was ready, by then, to answer any question about Ronnie that anyone might care to ask.

There was nothing obvious in the life of Ronnie that would have led directly to me or my own habits of invention, though I’d voiced him and played him. Once he had the means, the credentials, the bitcoins and the passwords, he was, in a sense, free, like a character in fiction who must express himself not merely according to his author’s wishes but according to some inner mechanisms embedded in his past and in his nature. ‘It begins with a character, usually,’ William Faulkner said, ‘and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.’ And I can only say that the Ronald Pinn I made up tended towards certain enterprises of his own volition and I let him. The websites on the dark web have a tendency to morph as quickly as the people manning them, but the illicit marketplaces – Silk Road, Agora, Evolution – opened up to him, and he was soon having conversations with secretive experts about drugs and false documents and guns.

An individual called Ronald Pinn, using his own pass-codes, paying with the bitcoins purchased in his name, bought white heroin and had it sent to his London address. It arrived in a small vacuum pack between two white cards in a jiffy bag, and cost about £30. He bought Afghan weed and it came the same way; he bought Pakistani cannabis. Addressed to Ronald Pinn, it all came to the empty flat and I had it checked for authenticity. At one point several packs of the powerful painkiller Tramadol came through, as well as other drugs, all ordered by and delivered to the only person ever associated with their purchase, Ronald Pinn. As the weeks went by, his exploits became more baroque and seemed like a stretch for his character. He began buying counterfeit money, which came at 50 per cent of the face value: for £200 you could buy £400 in fake money, and it passed all the basic tests. As an international space populated with anarchists and libertarians, non-conformists and government-haters, the dark web quite naturally gives itself to wide definitions of freedom. It points to the self-serving nature of power elites, decries corruption in governments and legal systems, satirises the ‘phoney’ war on drugs, and laughs at all officialdom and all attempts to curtail the freedom of individuals. It likes drugs, has no respect for official banks and has a fondness for guns.

Ronnie went in that direction. There were areas I wouldn’t allow him to go into – porn, for instance – but the Ronnie who existed last summer was alive both to drugs and to the idea of weaponry. It’s one of the contradictions of the dark web, that its love of throwing off constraints doesn’t always sit well with its live-and-let-live philosophy. There are people in those illicit marketplaces who sell ‘suicide tablets’ and bomb-making kits. ‘Crowd-sourced hitmen’ were on offer beside assault weapons, bullets and grenades. One of the odd things I discovered during my time with cyber-purists – and Ronnie found it too – was how right-wing they are at the heart of their revolutionary programmes. The internet is libertarian in spirit, as well as cultish, paranoid, rabble-rousing and demagogic, given to emptying other people’s trash cans while hiding their own, devoted not to persuasion but to trolling, obsessed with making a religion of democracy while broadly mistrusting people. Far down in the dark web, there exists an anti-authoritarian madness, a love of disorder as long as one’s own possessions aren’t threatened. The peaceniks come holding grenades. The Manson Family would feel at home.

When Ronnie Pinn went to see this world he found it welcoming and vile. He saw Uzis and assault rifles, bomb-making kits, grenades, machetes and pistols. As a man with cyber-currency, he was welcome in every room and was never checked. He was anybody as well as nobody. He could have been a teenager, a warrior, a terrorist or a psychopath. So long as he had currency he was okay. The only two sites where the website operators checked him out were Black Market Reloaded and Executive Outcomes, both suppliers of weaponry. You could get past them, but they did try to do check-ups. Other sites on the dark web asked no questions at all. Three hundred and fifteen grams of brand new gun with a nine millimetre silencer? An AK47 Black Laminate, ‘with a chrome-lined central barrel, adjustable rear sight and two 30-round magazines’? A Remington M24 sniper rifle? A series of Israeli-made semi-automatic pistols, costing less than the retail price of $2400? On the drugs discussion boards everyone seemed to be having the time of their life, but a sinister silence existed among the shootists. When a gun is purchased it arrives in many parts through the post, ready to be put together and used for who knows what purpose.

While Ronnie was becoming known in those circles, having chats, spending money, discovering what he and others could be and do, I was reaching back to see what more I could find out about the real Ronald Pinn. I stood one afternoon as an entire block of flats was being torn down on the Old Kent Road. I studied old photographs of Avondale Square and read through online chats where people remembered their childhood friends. I went to the former location of men’s clothing shops, now pound shops; someone said the real Ronnie’s family might have run businesses there. Nobody asked me why I was curious about this young man who died thirty years ago, as if it was normal to ask after people, as if that is just one of the things we do with our lives, asking after the dead. The cliché about reporting is that ‘ordinary’ people don’t want to have their lives invaded. But they do. More than anything they want to talk about who lived and who died and what changed. But who owns the narrative of a person’s life? Do you own your own story? Do you own your children’s? Or are these stories just part of what life manifested over the course of time, with no curator, no owner, no keeper who has the rights and holds the key? You have responsibilities and rights before the law, but do you own what you did and who you are, and is privacy a vain wish or an established right? Is there no copyright on one’s experience and only the ability of others to remember or forget? I kept wondering about Ronnie’s mother, whether she was alive somewhere. It seemed reasonable to expect that the story of Ronnie’s real life would be something she felt she owned, or had to protect, and that the story of his second life would not only surprise her but feel like an invasion.

By the time I walked up the streets to his old schools, peered into the halls where he ate his school dinners and read his old report cards, the Ronnie Pinn that came after him, and used his birth certificate, was present and available to the mass consciousness of the World Wide Web and the dark web in ways that would have made the real Ronnie’s mind boggle thirty years ago. It took three or four clicks to find the fake Ronnie and all his comments and many of the places he’d been. Before leaving my office to see the building where Ronald Pinn died in 1984, when I was 16, I looked into the possibility of buying the fake Ronnie a second passport, a Turkish one, and an ‘identity pack’ (a bundle of fake ID cards and utility bills tailored to the buyer’s chosen name and address, as well as their face). It was a busy morning. Using several bits of his fake ID, he got signed up for a gambling website. At his ‘address’ in Islington I found that he now had a tax code and was getting letters from the Inland Revenue. Was it only a matter of time before Ronnie was able to open a bank account, make investments, write his memoirs, and book a seat on a flight he would never arrive for?

With his fake self and his fake friends, Ronnie became like an ideal government ‘sleeper’, a supposedly real person who could infiltrate political groups and shady markets. He started as a way of testing the net’s propensity to radicalise self-invention, but, by the end, I was controlling an entity with just enough of a basis in reality to reconfigure it. Ronnie Pinn’s only handicap lay in his failure physically to materialise, but, nowadays, that needn’t be a problem: everything he wanted to do, he could try to do, except find a partner, but even that, though tricky, was not impossible. I simply didn’t go there for fear of fooling the innocent and learning nothing. He could chat people up online but when it came to meeting them, well, Ronnie was nothing, wasn’t he? His existence was powerful in the dark and busy world of self-invention, but like Peter Pan, he was a stranger to adulthood, and a grotesque outcrop of the imagination like Mr Hyde; he lived for a season inside the mind of the person writing this story.

The ‘people’ now moderating the dark web don’t care about the old codes of citizenship and they don’t recognise the laws of society. They don’t believe that governments or currencies or historical narratives are automatically legitimate, or even that the personalities who appear to run the world are who they say they are. The average hacker believes most executives to be functionaries of a machine they can’t understand. To the moderators of Silk Road or Agora, the world is an inchoate mass of desires and deceits, and everything that exists can be bought or sold, including selfhood, because to them freedom means stealing power back from the state, or God, or Apple, or Freud. To them, life is a drama in which power rubs out one’s name; they are anonymous, ghosts in the machine, infiltrating and weakening the structures of the state and partying as they do so, causing havoc, encrypting who they are. When the FBI attacks Silk Road and attempts to shut it down, as it did most recently two months ago, on 5 November, the resilience it shows is impressive. ‘Our enemies may seize our servers,’ the moderators of Silk Road wrote on their relaunched website, ‘impound our coins, and arrest our friends, but they cannot stop you: our people. You write history with every coin transacted here … History will prove that we are not criminals, we are revolutionaries … Silk Road is not here to scam, we are here to end economic oppression. Silk Road is not here to promote violence, we are here to end the unjust war on drugs … Silk Road is not a marketplace. Silk Road is a global revolt.’ ‘When you’re in a tsunami you can’t push back the water,’ the City of London Police Commissioner Adrian Leppard said recently, when talking about piracy and the failure to hold it back. ‘You have to start thinking very differently about how we protect society … Enforcement will only ever be a limited capability in this space.’

Ronnie Pinn, the invented one, was a single digit in ‘this space’. He achieved all the legitimacy I could glean for him in the time I had. But always I was drawn back to the ‘real’ Ronnie and what it meant to be out of the world for thirty years and then revived in a different guise. Eventually, I got a message from a woman I’d written to called Kathleen Pinn. In the first instance she said she thought Ronnie’s mother might still be alive, and, when I asked her to elaborate, she wrote again. ‘My family have never met up since my mother’s death in 1979,’ she said. ‘Glenys was living in Bermondsey then, that’s all I can tell you, I do not have her address.’ Eventually I found a number for her in a 1977 telephone directory, but the phone line was dead and the building was gone.

Eradicating the fake Ronnie was difficult. He had 68 followers on Twitter and I don’t suppose many of them noticed he’d gone; some of them were as fake as he was. But rubbing out a Twitter account leaves a shadow on the net. It used to be that real people could go missing and nobody would really notice, and nothing would be left behind. Life used to be good at that. But nowadays the fake identities are hard to abolish, and something of the fake Ronnie is indelible, his ‘legend’ part of the general ether. He has ‘metadata’, the stuff that governments collect, the chaff of being. And he will go on existing in that universe though he never existed on earth.

Ronnie’s last tweet was a single word, ‘Goodbye’, on 12 December 2014; then I deactivated his account. ‘We will retain your user data for 30 days,’ Twitter told me, but ‘we have no control over content indexed by search engines like Google.’ His unreality was now embedded in the system; it would never have to explain itself. On Facebook, there was a final ‘friend’ request from someone called Peter Lux: I have no idea who Mr Lux is, or why he wanted to friend Ronnie Pinn, or if he is even real or just another figment shoring up his legend. Facebook doesn’t make it easy to deactivate an account: it wants you to stay. ‘Laura will miss you,’ the message said, choosing one of Ronnie’s ‘friends’ at random. And then: ‘Your 23 friends will no longer be able to keep in touch with you,’ before warning me that ‘messages you sent may still be available on friends’ accounts.’ When it let me leave, it demanded that I tick a box saying why I was leaving and I chose one that seemed right: ‘I have a privacy concern.’ Reddit was also sorry to see Ronnie Pinn go and his conversations, about freedom, about guns, about drugs would never necessarily be wiped and would remain up there like a dead star.

Ronnie’s online gambling account, which was set up using false documents, couldn’t be closed down. Craigslist promised his account would self-delete after a few months of inactivity. The bitcoins laundering service, a secret service alert to the very last, had no record of Ronnie buying anything and his ‘presence’ disappeared as soon as I deleted his email accounts and ripped up the passwords. ‘We’re sorry to see you leave!’ Gmail said, but the we that was sorry was never identified, and traces of who Ronnie was and what he did through various email accounts are now hidden in servers around the world. My invention had become so present in the official world of things that as well as a tax code he had a national insurance number, though I had never tried to register Ronnie as a taxpayer or as someone drawing a salary. Banks were soliciting his custom, and, though he wasn’t on the electoral roll, it seemed only a matter of time. The flat in Islington had nothing to do with Ronnie and no one who lived in the building had ever heard of him, though it felt strange when I went to the hall for the last time and picked up his letters.

I’d almost given up when I found Ronnie’s mother. Her name was on a register I had in my possession all along and it seemed to prove she was still alive. There was no phone number and the house was to the north-east of London, almost in Essex. I held onto the details for a few weeks more, putting a card on my desk with the address written on it. Every morning I looked at it and wondered if solid reality wouldn’t yet prove something more. Then, one morning at the end of November while it was still dark outside, I got up and got dressed, put my recorder and a notebook in my bag and walked out into the rain. The Tube was crowded at Bank, everyone keeping themselves to themselves, the Indian lady in sandals and socks, the young man with earphones and jagged hair lost in beats not his own; the lady across from me with the Aztec necklace, the man in the North Face jacket, the schoolchild looking out anxiously for her stop. All the while I was thinking about Mrs Pinn. Would she be out of bed now, making tea and wondering what the day would hold? Would she be pulling back the curtains, coming down the stairs, not knowing that today was the day a stranger would come to speak to her about her son? I thought about her as the train stretched away beyond Central London and the commuters left group by group until, past Barkingside, there was only me. The morning’s newspapers were blowing down the carriage, and it grew light over the fields.

I walked for a mile or so to find the house. I wasn’t sure it would be the right one, or that the Mrs Pinn I’d find there was the person I was looking for. There was a strong chance she wouldn’t want to speak to me and would hate the whole thing. I knew all that, and the street-lamps blinked off as I walked under a flyover and past a bank of skinny trees. An elderly man stood behind a hedge at the end of Mrs Pinn’s street. The path was neat as I walked up to the house and the garden was simple. There was a dog barking inside and I stood for a moment. An elderly, good-looking woman came to the kitchen window and we each stood staring for a second. She was wearing a leopard-pattern dressing-gown and holding the dog’s tiny yellow ball. She opened the kitchen window expecting a salesman and was surprised when I said her name. I said I wanted to speak to her about Ronnie and I would explain everything. Her eyes widened and she seemed astonished for a second as she said the word ‘Ronnie’. I noticed she squeezed the yellow ball before nodding and coming to the door. ‘It will be nice to talk to you,’ she said, letting me into the hall. ‘You must be about his age.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Oh, Ronnie,’ she said. ‘There was nobody like him.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.