Polling day , which we’d waited for in a fervour, was odd and quiet. Mist pressed at the windows. I felt convalescent and washed out, and fair enough, for the last ten days I’d been living on a mix of Facebook and Nytol – Facebook because you can be everywhere at once and the ‘official’ media had been solidly and relentlessly Unionist. Even the BBC. Facebook brought me the blogs and pictures, cartoons, arguments, discussion and outrage that kept us all ablaze these last few weeks and months. Bella Caledonia, Wee Ginger Dug, Rev. Stuart Campbell, Alec Finlay, Wheelie Bins for Yes – a cataract of stuff. God knows, in my hours online I wandered down some peculiar byways (the Spectator comments pages). The Better Together ‘Patronising Lady’ advert kept us entertained for ages. (Watch the ‘Valium Mix’. Or the one with subtitles. I love that ‘Eat your cereal’ immediately dropped into the language.)

The most surreal moment, surely, was the arrival in Glasgow of sixty Labour MPs, trucked up from the south to make us see sense. They were chased through the streets by a guy in a rickshaw who was playing the Star Wars theme and hollering through a megaphone: ‘Welcome, imperial masters! Welcome to Scotland, imperial masters! People of Glasgow, here are your imperial masters!’ As one blogger said, that was surely the moment Labour in Scotland died.

In my small town in Fife, where we’ve lived for twenty years, the ‘Yes’ posters in windows outnumbered ‘No’ ten to one, but posters can’t vote. At 78, my dad was one of the oldies who was inclined to vote ‘No’. He knew fine well his children and grandchildren were voting ‘Yes’.

‘But dad,’ I said, ‘do you not think independence is inevitable?’

‘I daresay you’re right.’

‘But you’re still voting “No”?’

‘I am.’

My daughter and I voted early. It was the most simple ballot-paper on earth, but still, I was so nervous I had to check and recheck, making sure the X was going in the right box.

Zinging with anxiety, we drove down to Edinburgh on Thursday evening to watch the results with friends in Marchmont. ‘Yes’ posters again well outnumbered ‘No’. The suburbs had been different: we saw plenty of perjink signs saying ‘No Thanks’, stuck on privet hedges. My friends are Scots born, English born, Italian born. Why do I have to insist on that? Because of the constant bitching that the ‘Yes’ movement was simply ‘anti-English’. No one wanted to be alone that evening. We ate a carry-out curry and waited for the first declarations. A bottle of malt appeared. Clackmannanshire declared. Then Orkney. Then the rest.

I went to bed about 3 a.m., rose again at six, by which time it was over: 55 per cent of the voters had left their quiet houses, voted ‘No’, gone home and shut the door. At seven David Cameron was on the radio. He intoned the words ‘our United Kingdom’ so many times I thought I’d be sick. Whose United Kingdom? Theirs. The Eton Mess and their cronies. Big Business. Neocons. The warmongers. Not ours.

We left Edinburgh at lunchtime. The motorway was, well, it was a motorway. Business as usual. Team UK. Eat your cereal.

Did we cry? Of course. I did anyway. I spent Friday afternoon lying on the settee, happed in a blanket, the cat asleep on my throat. We’d worked and hoped, and boy our hopes had run high. When that opinion poll appeared putting ‘Yes’ ahead, the one that sent Westminster into a flat spin, I actually thought, my god, maybe we can swing this. It felt weirdly exposed to be in the lead. I was almost glad when ‘Yes’ slipped behind again. By then, of course, Scotland was suffering full-scale Unionist psychic battering, Project Fear in hyperdrive. But for a few weeks the bullying, elitist, rapacious United Kingdom establishment had stood exposed. Here. In my country. Scotland. It was absolutely bloody brilliant. It was beautiful and now it’s over and we’ve shed a tear and that’s that.

Except, it’s not.

I was still on the sofa when Phil came in to tell me Alex Salmond had resigned. He wasn’t our ‘leader’, though he’d sure impressed us. I got up and went to the laptop. The Times front page was online: ‘Salmond quits as powers for Scotland are blocked’. The devo-max ‘vow’ was already falling apart, surprise surprise, the ‘vow’ that Cameron, Miliband and Clegg had all signed and presented to the Scottish people on the front page of the Daily Record, where it was mocked up to look like ancient parchment. They didn’t even have the grace to wait till Monday.

On Saturday night, neighbours down the road lit a bonfire. It felt like a wake. It was a wake. We talked about an online community that had immediately emerged, the ‘45’, the 45 per cent of Scots who voted ‘Yes’ for independence, democracy and equality, who believe Scotland is a country not a brand, who believe we could and should re-dream, redesign and retool our nation from bottom up, and who truly kicked the arse of the British establishment. Of course, the figure ‘45’ – the date of the Jacobite Rising – has great resonance in Scotland. Perhaps that’s not an association we ought to make, but that night the reference was lost on no one.

The bonfire blazed and we kept talking, as we have in pubs, clubs, trains, factories, village halls and hairdressers and online for weeks and months. We began to cheer up. Within a week of the result, membership of the SNP more than doubled. Membership of the Green Party trebled. The Scottish Socialists are back. Women for Independence tweeted that they were looking for a bigger conference venue. When a pro-independence party rises from the ashes of Scottish Labour, as it will, and the elders pass and my children’s generation come to their true maturity … Let’s just say I’m keeping my ‘Yes’ badge safe in the button tin.

Kathleen Jamie

Project Fear has had a temporary victory in Scotland but its legacy will not be a return to the status quo ante either in Scotland or elsewhere. The mind of the Scottish nation has stirred to new activity. Every single parliamentary constituency in Glasgow voted ‘Yes’. Henceforth the divide in Scotland will always be between the Unionists and those who want independence, and that will be the main issue in 2015: if Labour is dethroned by the SNP, say farewell to the UK state.

As for the rest of us, we live in a country without an opposition. Westminster is in the grip of an extreme centre that is the coalition plus Labour: yes to austerity, yes to imperial wars, yes to a failing EU, yes to increased security measures, and yes to the status quo. And its leaders: Miliband, a jittery and indecisive leader presiding over a parliamentary party (including his shadow chancellor) that remains solidly Thatcherite; Cameron, a PR confection, insolent to the bulk of his own people while repulsively servile to Washington and often to Beijing. Clegg barely needs a description. His party will suffer in the next election and we might soon be deprived of his presence. All are flanked on the right by Ukip, whose policies each tries to pander to in its own fashion. Euro-immigration is becoming an English obsession, even though it was this country that carried out Washington’s orders to expand the EU so that it lost any chance of social or political coherence.

What of our local institutions? The neutered BBC that during crises at home (Scotland) and wars abroad (Gaza, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan) is little more than a propaganda outfit. The NHS? Crippled by Blair and Brown with their PFIs and privatisations and now well on its own way to privatisation thanks to the last Health Bill. The railway companies? Loathed by the bulk of their ‘customers’ they still receive state subsidies although the idea of renationalising them for the public good is rejected by the extreme centre.

Politically, we need a party to the left of this centre. The constitutional mess can only be sorted out by a constitutional convention that gives us a written constitution which sweeps away all the cobwebs (the antiquated and unrepresentative voting system, the unelected second chamber, the monarchy etc) and guarantees the right to self-determination of nations within the UK. This will not happen unless there is a grand remonstrance from below. Here the Scottish campaign for independence offers a good model.

Tariq Ali

After the 1979 referendum, which mustered too few ‘Yes’ votes to win a Scottish Assembly, there was a lot of heartbreak. Many people, contemplating self-government, had begun to think that Scotland could be a place worth staying in, or returning to. This time it’s different. The ‘settled for a generation’ rhetoric began to dissolve within hours of what was a solid ‘No’ vote to independence. At first ‘Yes’ supporters shed disbelieving tears. But then the last minute promise of ‘more powers’, the ‘vow’ by the three Unionist parties, started to unravel as David Cameron locked it in with ‘English votes for English laws’.

Many ‘No’ voters wanted what a plurality of Scots have wanted for nearly forty years: to govern themselves as other small nations do but, if possible, within the United Kingdom. They were cheated too. Devo-max, whose minimum version means full fiscal autonomy, would have suited them. But Cameron kept it off the ballot paper, and the ‘more powers’ supposedly on offer are nothing like as strong.

The sense of onrush, of irresistible change, has survived the ‘No’ vote. For a party in defeat to double its membership in five days – that sort of thing just doesn’t happen in Britain. Maybe the SNP will oust Labour from Scotland in the 2015 general election and seize the balance of power at Westminster – as the Irish Parliamentary Party did a century ago. Or maybe the next collision will come with the EU referendum. No English region save London now wants to stay in Europe. But 59 per cent of Scots do, up from 40 per cent only two years ago. What if the Scottish Parliament refused to take part in the referendum, or defied its verdict? Nothing’s impossible in Scotland now – except a return to the status quo.

Neal Ascherson

The ‘No’s have it, and nothing will change. It was reported on 24 September that ‘Downing Street had been inching towards joining the military effort against Isis, but the prime minister had acted cautiously because he knew that British involvement could have played into the hands of the Scottish first minister, Alex Salmond, during the independence referendum.’ That Salmond! He must have held things up for a fortnight.

I remember a politician in the 1970s (it was a time when ‘the balance of payments’, as opposed to ‘the deficit’, kept Westminster in irons) saying that the only hope for Britain was if it could stop pumping up its imaginary standing and influence in the world, and try – it would take generations – to give its people the standard of living and measure of equality achieved by the Netherlands. That project is again on hold.

One thing the Scots will not now have the chance of deciding on is their safety. A friend reminded me that in 2000 the Ministry of Defence, assessing the dangers of a major accident at the Trident base at Faslane (25 miles from Glasgow and about forty from half the population of Scotland) concluded that the ‘societal contamination’ that would result meant that ‘the risks are close to the tolerability criterion level’. But these are old-fashioned issues. Onwards to Raqqa and Mosul!

T.J. Clark

For ‘Yes’ voters 19 September was a very dreich day. A 6 per cent swing would have made all the difference; but it didn’t happen. Older voters tended to be the most staunchly Unionist: time may not be on the Union’s side. As yet, despite the Westminster party leaders’ widely publicised referendum ‘vow’, it’s not clear what will emerge. We may get a flavour of devo-max, the option Daveheart was determined to keep off the ballot paper, but which the Tories have edged towards; or we may get devo-min, which the Labour Party seems to prefer. Scotland voted to remain a stateless nation. England is feeling increasingly awkward about being one too.

Whatever happens in the longer term, for now there should be an English Parliament. Far too much time in the British Parliament is spent on English affairs. The British Parliament should deal with pan-British issues; national parliaments in the four nations should deal with devolved business. If England won’t pay to have its own parliament, and goes for the cheap option of having ‘England-only’ days at Westminster, Westminster will seem all the more Anglocentric. If devo-max proves illusory; if Ed Miliband (loved by many Scottish voters about as much as Gordon Brown is loved in England) proves unelectable; or if there is a vote for UK withdrawal from Europe, support for Scottish independence could surge.

Robert Crawford

The Scottish Referendum of 2014 is a watershed in the history of Britain. The Union of 1707 as we have known it is no more, even if some kind of union between England and Scotland continues. Scots have been ‘promised’ more powers for the Holyrood Parliament, though discontent on delivery times has already surfaced, while other concessions, yet to be finally determined, are also promised for England. The prime minister is fighting on two fronts. The historical precedents for such a campaign are hardly inspiring. Never since the Jacobite army reached as far south as Derby during the ’45 Rising has the British establishment been so reduced to such an extraordinary and risible state of panic.

It seems to me that there are only two possibilities which can restore stable amity between the signatories of the Treaty of Union. With anger increasing in many parts of England about the ‘goodies’ promised to Scotland, only full-scale federalism can assuage the aspirations and anxieties of the four nations. The governing capital of such a federal state should probably be sited in Carlisle. At least five new parliaments in England would have to be established with historic names such as Mercia, Wessex etc. Westminster has neither the appetite nor the intellectual capacity to deliver on any of that and so the much more likely possibility is another referendum in the next few years, which will probably result in a landslide ‘Yes’ victory, thus ending the Union for ever.

Tom Devine

It wasn’t about nationalism, but about more responsive and accountable government. It wasn’t about whether we’d be richer or poorer, but whether we could be fairer. Scotland isn’t a region: it was a small, distinctive nation before the Union of 1707 and continued to be so. It’s a paradox of our political system that nuanced opinions are compressed into polarities: leftwing or right, progressive or conservative, ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Most of us felt conflicted. I voted ‘Yes’ because after twenty years in full-time education, and fifteen delivering healthcare, I couldn’t think of many practical reasons to celebrate the Union or support its direction of travel. Perhaps it would have been different had I been a banker or scientist instead of a doctor, but my experience suggests that people living in Scotland have been better served by decisions made closer to home.

I could think of plenty of emotional reasons to vote ‘No’, not least that having enjoyed two hundred and fifty years of imperial opportunities, it would be ungracious of Scotland to leave just because the empire had run its course. But the wish to be gracious didn’t count for much against the worry that a tradition of social justice was under threat, and that, despite centuries of Scottish internationalism, we might soon find ourselves cast out of the EU.

Two slogans condensed the arguments: the Greens’ ‘Seize the Opportunity’ versus Labour’s ‘It’s Not Worth the Risk’. The risk-averse won, and their anxieties should be respected. Many on both sides were dismayed by the immediate shift in the agenda as soon as ‘No’ was secured. But the most optimistic of us were delighted by the tremendous energy of the campaign, and the unprecedented levels of political engagement. Visions of a fairer Scotland and UK have been created; if those are implemented, all of us will have won.

Gavin Francis

On the evening of Friday, 19 September, hundreds of loyalists congregated in George Square in Glasgow. Some bought Union flags from hawkers; most had brought their own. Women dressed in red, white and blue sang ‘you can stuff your independence up your arse.’ Expensive cars disgorged burly men from Ayrshire and Fife. A Rangers banner was attached to the metal railings in front of the cenotaph. Sections of the crowd chanted ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘No Surrender’. Some gave Hitler salutes. Eleven people were arrested.

Britain First had asked its supporters to meet in George Square at 6 p.m. The group was founded in 2011 by a former BNP staffer called Jim Dowson, who is from Cumbernauld but now based outside Belfast. Also among the crowd were members of a Rangers supporters’ outfit called the Vanguard Bears. Last year, they met the Progressive Unionist Party – the political wing of the Ulster Volunteer Force – in order to discuss their joint opposition to Scottish independence. The Vanguard Bears regularly publish personal information, often gleaned from social media, about Celtic fans and Irish republican sympathisers in Scotland.

The past few years have been tough for Scottish Loyalism. Rangers went into financial meltdown and is still making its way back up through the Scottish football leagues. Orangeism, once a force in Scottish politics, is now largely confined to working-class men in the old mining towns that ring Glasgow and Edinburgh. The Orange Order – the most pro-Union organisation in Scotland – was effectively barred from joining Better Together. Loyalism still played a role in the referendum, however. The weekend before the vote, more than ten thousand members of the Orange Order gathered in Edinburgh for their largest march in Scotland in living memory. The parade was peaceful but the mood on the edges was belligerent. ‘We’re taking back our city,’ a young man told me on the train to Edinburgh that morning. The march – widely reported as a ‘pro-Union’ rally – emboldened Scotland’s Loyalists to try to ‘take back’ Glasgow the day after the referendum.

The independence debate was celebrated for energising disenfranchised working-class communities, but, less conspicuously, it also galvanised Scottish Loyalists, another alienated cohort. Political leaders were encouraging Scots to fly the Union flag and have pride in Britain’s imperial past. As Scotland went to the polls, an image of Britannia circulated online, depicting Alex Salmond’s severed head skewered on her trident. Scotland’s much heralded democratic renewal cuts both ways: in the view of many Loyalists, the referendum result is a vindication of their deeply sectarian worldview.

Peter Geoghegan

The relief was visceral. At home in Glasgow on referendum night, I had the jitters and went to bed early; but coming to at 4 a.m. I experienced a calm I hadn’t felt for several weeks. I sensed that the nationalists had lost. Total silence: the sound of the quiet Unionist majority celebrating. Apart from a few Loyalist bigots, whom the ‘No’ camp denounced, there was no triumphalism. That came a couple of days later in an interview on Sky News when Salmond declared victory: ‘The destination is pretty certain, we are now only debating the timescale and the method.’ His argument rested on polling data that showed a majority of Scots below the age of 55 voting for independence. The ‘No’ side, it transpired, had compiled its majority from the wrong voters. According to Salmond, the elderly had betrayed Young Scotland. Mischievously, he also noted that referendums were not the only route to independence; there were other avenues to explore. Nationalists took to Twitter to set out the scenarios. Might a majority of SNP MPs in Scottish seats in the general election of 2015, or in the Scottish Parliament elections in 2016, be enough for a unilateral declaration of independence? Meanwhile UK politicians – trusting in the democratic bona fides of their nationalist opponents – headed for the thickets of constitutional reform. Here swift delivery of further devolved powers to Scotland is essential. Other issues – the West Lothian question and my own hobbyhorse, a senate or Bundesrat to replace the Lords – can wait. In the interim it’s essential that the SNP acknowledges – without the sly equivocation of its soon to be former leader – the sovereign will of the Scottish people. Otherwise, with the ‘No’ vote split among the contending UK parties in a general election, we face the possibility of the SNP claiming a mandate to overturn a clear-cut referendum result. Relief is tinged with despair. Fair play, civility and respect for the democratic process – the fabric of British political stability – are as much in need of repair as our constitution.

Colin Kidd

Cameron used the victory of ‘No’ to resurrect the West Lothian question at a speed not surprising in such a partisan opportunist. Ed Miliband is right to resist his rushed attempts to exploit promises hurriedly made to Scotland to justify legislation which would allow only ‘English’ MPs to vote on ‘English’ measures. A proposal of that sort is wrong for two reasons. First, it is wrong in principle to introduce such important constitutional changes in a matter of weeks. No better, in fact, than Salmond’s attempts to rush Scotland into independence without any idea how independence might work. Second, such legislation would fundamentally destabilise British government. It could create a situation where a government which possessed the confidence of the House of Commons was unable to pass the bulk of its legislation. That is what the Tories want, on the assumption that they would normally make up a majority of English MPs, but it is a hopeless way to run a country. English votes for English legislation could work politically only if Scotland did indeed leave the Union. As a matter of political logic the Tories should have favoured a ‘Yes’ vote. You cannot want Scotland to remain within the Union and have English votes for English legislation. The political system is too inflexible to allow it.

Scotland’s continued membership of the Union is compatible with English votes for English legislation only if the House of Commons is elected by some form of proportional representation. That would at least diminish the chances of an ‘English’ veto, whereby the government of the day is rendered helpless by the over-representation of the Conservative Party in the South of England.

The argument in favour of English votes for English legislation rests on the assumption that England is socially and economically homogeneous. But it is highly diverse and its different parts have different needs. If Scottish MPs should not be able to vote on English issues why should Surrey MPs vote on legislation which would harm, say, Durham and Northumberland? One reason parliamentary legislation is not more harmful to the North of England under Conservative governments is that Scottish MPs can vote on English matters. If there is to be constitutional reform it has to be carefully considered and not just a Tory ramp. In the absence of a reform of voting procedures, the present constitutional structure of the United Kingdom is probably the one that works best.

Ross McKibbin

The early Scottish referendum results didn’t look good for the would-be dividers of the kingdom. My pro-independence Orcadian friend, down in London for a wine fair, went to bed before 3 a.m., disconsolate, not long after a furious thunderstorm lit up the deserted streets and made drums of the cars. I stayed awake long enough for the moment around four when my hometown of Dundee went heavily for ‘Yes’, swiftly followed by another ‘Yes’ in West Dunbartonshire. Suddenly the two camps were neck and neck.

It didn’t last. Almost at once ‘No’ results came in from the two traditionally SNP areas close to Dundee, Perth and Angus. If the districts that had reliably delivered votes for the Nationalists for so long didn’t want independence, what chance was there it was going to happen? Just before five, Glasgow delivered its underwhelming ‘Yes’, and I turned in. I got up a few hours later to find my friend sitting on the sofa, staring biliously at the TV, with an expression as if he’d been forced to swallow an entire bin-end of corked Syrah.

‘How’s it looking?’ I said.

‘They’re talking about new powers for London!’ he spat.

It was true. In the space of a few hours, a passionately fought campaign for and against Scottish independence from England, an unprecedented democratic mobilisation of an entire people, had mutated into a burgeoning campaign for English independence from Scotland. When David Cameron ambled out of Number Ten, it was not, as had seemed possible a few days earlier, to resign, having ignominiously ‘lost’ Scotland, but to announce the launch, effectively, of an English devolution campaign – to challenge the prevailing anomaly whereby MPs elected to Westminster from Scottish constituencies get to vote on certain issues that affect only England, like health, education and transport, but their English counterparts don’t get to vote on corresponding issues in Scotland.

It could all come to nothing. It could end up with a terrible mess. Or it could end up with the complete federalisation of Britain: the creation of an England-only parliament to match its counterparts in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, dealing with everything from taxation to the English NHS, and a British parliament dealing with defence, foreign affairs and trade. This England-only parliament could even be several parliaments – London, Anglia-Essex, Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria, for instance.

This is heady stuff, and would seem unlikely to attract Cameron, were it not that he can destabilise his political opponents just by talking about it. Pursuit of English devolution distracts the Lib Dems, setting them off towards federalism like ferrets after a rabbit. The idea of excluding Scottish and Welsh MPs from decisions on the English NHS, English schools and English housing has put Labour – extraordinarily negative about its own future as an English party – on the back foot.

Most attractively for Cameron, it would enable him to woo Ukip supporters by presenting himself as the champion of England against a remote, vaguely socialistic authority imposing alien rules and values: Scotland or, to be more precise, Britain-unduly-influenced-by-Scotland. How bizarre and absurd, and how tragic for Scotland, that having voted for continued belonging to the United Kingdom, this small country might find itself cast by the Conservative leadership as a convenient surrogate for Brussels.

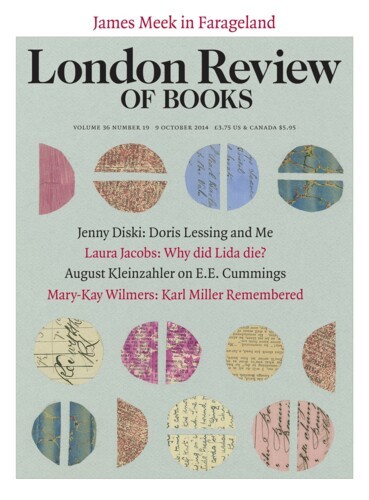

James Meek

Now the discussion turns to what England wants, which was bound to happen, whether the result had been ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The focus on Scotland, not just in the last few weeks but (with occasional attention paid to Wales) the last few decades, has left the English question on the back burner for too long. The impetus to address it is now clear, especially for the Conservative Party, which feels it has a lot to gain from playing England off against Scotland. But although the moment looks propitious, it will be very difficult to get the timing right. The problem is a basic one of asymmetry. It’s not just that England is so much bigger than Scotland, which means any attempt to give England an equivalent say in its own affairs risks unbalancing the United Kingdom in favour of one outsize member. It’s also that England lacks the institutions onto which power can be devolved.

The reason it’s easy to talk about greater powers for Scotland (or Wales or Northern Ireland) is that they have parliaments or assemblies ready to receive them. England doesn’t. In this sense the timing is all wrong. For devolution to work, first you need to go through the process of establishing the appropriate structures, then you can decide what to do with them. Cameron seems to think it can be the other way round: simply establish the appetite for constitutional transformation and the structures will fall into place. It’s almost Leninist. Who needs a bourgeois revolution when the chance opens up for a communist one? Leninism has its attractions at moments of political upheaval. But it takes a ruthless political will to implement. I doubt whether Cameron has that.

What is the appropriate scale for English devolution? Is it the nation, which would need its own parliament and would then be in a position to bully the parliaments of the other bits of the UK? Is it the regions, which might entail the creation of soulless, bureaucratic entities (such as a North-Eastern assembly, although this was overwhelmingly rejected by the people of the North-East in a referendum in 2004) or more soulful, quixotic ones (a parliament for Cornwall)? Or is it the cities? Looming behind these questions are the enormous imbalances within England itself, where London and the South-East continue to hoover up an excessive proportion of national wealth and resources. And behind that configuration is the dominant position of the City of London, which distorts the economy of the whole UK.

Cameron doesn’t just face a threat from disgruntled Scots who see him turning an unambiguous pledge into a bargaining chip with his own party. He also risks being outflanked on the other side by the pro-City, anti-EU Boris Johnson, who could probably unbalance the UK constitution all on his own. There is an election looming. It is an almighty mess. The leaders of all the main Westminster parties are paying the price for having put off for far too long the tricky business of readjusting Britain’s over-centralised, outmoded constitution. They have been waiting for a big enough prompt to get them going. Now that the prompt has come they don’t know what to do next. There are lots of things a democracy can muddle its way through but constitutional reform is probably not one of them.

David Runciman

My dad, who lives in Selkirk, is 85 and voted ‘No’. His reasons, he says, were emotional. He likes being part of Britain, and didn’t want the Union to split apart. And he doesn’t like Alex Salmond, whom he considers ‘greasy’ and ‘ a tricky individual’. My dad, in short, is one of the ‘declining constituency of elderly voters’ that Irvine Welsh, among others, has identified as the ‘No’ vote’s main and inevitably shrinking asset. I think about that, being 85 and frightened about your country’s break-up, when I can’t sleep at night.

I didn’t have a vote because I live in London, but if I had, it would have been what Richard Gunn on Bella Caledonia called a ‘Yes, But’: a cross in the ‘Yes’ box, but with ‘caution and reserve and doubtfulness … present from the very start’. One of those many reservations would have concerned all those wishy-washy metaphors about bad marriages and arrested development and identity crisis etc. Politics, I think more and more as I get older, is best approached as a necessarily dull and painstaking discipline, with as little dabbling as possible in dreams and psyches. So I’m now quite looking forward to the years ahead of wrangling and negotiations and to seeing what can be done to make them as open and just as they can be, in process and result.

I went to bed as usual on the night of the referendum, and woke up when the thunder started, with a smell of burning ozone, around three. That’ll be the splitting starting, I thought. Better check that Dad’s all right. Then it was 6.20 and Salmond was conceding and all the strange excitement of the previous months was gone. I didn’t bother phoning my dad, or anybody else, that day at all.

Jenny Turner

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.