Valérie Trierweiler ’s book about her life as a grande Hollandaise and France’s first lady, and then – abruptly – neither of those, is more hair-raising than the extracts in Paris Match suggested when they appeared on the eve of publication at the beginning of September. Her pain levels are out of control; rage, jealousy, self-pity, self-flattery and malice are the indices, on every page. This isn’t a book so much as a casualty struggling to rise to its feet but disabled by the fury of its author. François Hollande is the target: he was elusive in his personal life; he embarked on an affair with the actor Julie Gayet and denied it until he could no longer do so; he announced the break-up with Trierweiler in a peremptory and hurtful way, as she was hustled offstage; he was – and remains – involved in an obscure political dance with his ex-partner Ségolène Royal, also a party notable, who ran for the presidency in 2007. (Royal has just been appointed minister for the environment.)

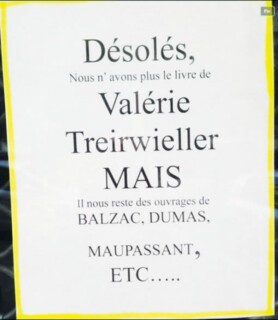

Trierweiler wants to bury her little ex alive in the ruins of his botched Socialist administration, preferably with her ex’s ex. The book is grim; it’s scarcely a triumph of journalism (she’s a kind of journalist) or feminism (she’s a kind of feminist), even if it manages to undermine Hollande. The trouble is that it does her no favours in the process: if you insist on dishing out your revenge straight from the oven you’re likely to get burned. Still, it’s worked wonders for the kind of indiscretion the French aren’t meant to like, and the figures are there to prove it. In France Fifty Shades of Grey sold 100,000 copies in five days. Trierweiler, who doesn’t do grey, sold 145,000 in four; a first run of 200,000 was followed by another of 100,000 and then another of 270,000. On a standard royalties contract she’s probably earned between 1.2 and 1.4 million euros. Over-excited journalists have put it at three or four million.

The most damaging story to do the rounds comes towards the end of the book, which is a first-person ramble set in a post-break-up present with flashbacks all over the place. Flashback to an unspecified Christmas, and Valérie Trierweiler takes Hollande down to eat with her family. The Massonneau clan are people of modest means, as she never ceases to remind us, and while Hollande is affable enough in their company, he can’t help telling her once they’re outside that they’re ‘quand même pas jojo’ – not a pretty sight. This is the sort of remark from a left-leaning head of state presiding over an austerity programme in a country with unemployment at 10 per cent that is sure to get people’s blood up, and Trierweiler makes the most she can of it, going on in a mawkish way to apologise to her parents – in the book! – for having brought it up and rounding on Hollande for preferring the company of Enarques and witty mondains like himself to her own wonderful family. It’s here that she drags in another of Hollande’s class jokes: ‘In reality the president doesn’t like the poor. A man of the left, he refers to them in private as “les sans-dents”, very proud of his witticism.’ (It’s a joke about the word sans: les sans abri, people sleeping rough; les sans papiers, undocumented migrants; sans domicile fixe, homeless; sans droit ni titre, squatters. Etc.)

These remarks are pas jojo in print, but why should a socialist with a subversive streak of irony – about himself and others – be obliged to affect a saccharine piety about disadvantaged people when he’s in private? Then again with Trierweiler there was no such place as private and he should have known better. As first lady she was quick to insist that private and public should remain discrete, but the affair with Gayet set her straight (it was also the reason she only lasted two years at the Elysée). She’d spent far more of her adult life in political journalism and now she has a killer story in which the private and public are caught in flagrante delicto so often and in such bizarre positions that you can’t tell them apart after a few pages. He’s squandered our relationship plus his five-year term. He’s in denial about our relationship plus his ratings are disastrous. He broke his promises to the steelworkers plus he’s lying to me about the Gayet woman. He’s in cahoots with Royal – I’ll see her hang from a specimen tree at the back of the Ministry of Ecology – plus he can’t get his own nomination for 2017 in order (some truth here). In this blurring of categories – a dry-ice effect presented as the fog of war – Trierweiler moves back and forth in pursuit of her enemy.

Another strategy: she repeats remarks Hollande has made to his colleagues and comrades, to complicate his working life and spread a little poison round the party. They’re remarks of the sort that would normally emerge in a biography after a person’s death or retirement from office, and we get the point. It’s not just Ségolène Royal – that’s an upside-down hanging, by the way, like Clara Petacci’s – but Laurent Fabius, currently the foreign minister, and Martine Aubry, daughter of Jacques Delors (Hollande’s mentor) and a runner for the PS nomination in 2011. Aubry is still a powerful figure in the party – currently mayor of Lille – which is surely why Trierweiler remembers her little man describing his rival in the primaries as ‘mad and unstable’. And in the brief days of presidential pillow talk – sharp memory – he confessed to her that he felt sorry for Fabius. Why? she asked. Because he failed: he never became president. None of this makes Hollande’s day-to-day business any easier.

Trierweiler has fought dirty and won her way into the history of the Fifth Republic. The success of her book explodes a rickety French exceptionalism on kiss and tell. The debris can’t be reassembled after this. Eighty, ninety years from now, modules in history may well invoke Hollande’s failure to talk Brussels into a compromise on austerity in 2012. If they’re smart they’ll record his forced march to a supply-side recovery that failed because, unable to raise the deficit, he was obliged to lift money from the family budget to boost the private sector: result nil-nil. They may note the fiscal scandals in his cabinet and the intervention in Mali. But leaving out the Trierweiler affair would be like leaving Wallis Simpson out of a module on the House of Windsor.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.