One of Baudelaire’s Petits Poèmes en prose, ‘Le Joujou du pauvre’ (‘The poor child’s plaything’), opens with the remark that very few amusements are free of guilt, but he knows of an ‘innocent entertainment’: a flâneur out for a stroll can fill his pockets with fairings – a rider on a horse with a whistle for a tail, or a clown on a string – and then, when he comes across one of those ‘unknown and poor’ street waifs of 19th-century Paris, give him a toy and watch his eyes widen. At first, Baudelaire writes, the urchin will hesitate to take it, doubting his luck, but then he’ll snatch it and run off, like a stray cat tossed a scrap which then skulks in a corner to eat it.

‘Le Joujou du pauvre’ goes on to expose something intrinsically disquieting about dolls: the deathly antithesis to life and consciousness that they embody. Baudelaire describes how he once saw a boy who was ‘beau et frais’, primped and pampered, wearing a coquettish country outfit, with next to him, lying on the lawn, a doll as beautiful as its owner, varnished, gilded, attired in purple, plumed and sparkling. But the toy doesn’t interest the child. His gaze is intent on something ‘between the thistles and the nettles’ on the other side of the park railings: a pariah urchin (‘un marmot-paria’), filthy and smelly and rickety (Baudelaire, lover of disease and dirt, piles it on), who is holding out his own toy for the other boy to see. He is shaking the cage, baiting its inmate – ‘a live rat!’ The poem ends: ‘And the two children laughed at each other in a brotherly way, and their teeth were equally white.’

A live animal is so much more fascinating than the splendid doll, for reasons that underlie the erotics Marquard Smith explores in his peculiar and highly equivocal study. Yet a doll promises everything the rat in a cage can give and more: she/he/it can be a human friend, a dream lover come to life with whom one may do as one wants – in every form of engagement, from tender care to sadistic self-pleasuring. A doll will not bite, will not let rip with her tongue. Rilke describes this ideal complicity in ‘On the Wax Dolls of Lotte Pritzel’, an impassioned and influential essay about dolls: ‘made into a confidant, an accomplice, like a dog, but not as receptive’, ‘dragged as companions into cots’; the dolls ‘themselves took no active part in these events,’ ‘letting themselves be dreamed’.

Smith calls his subject Pygmalionism, or sometimes ‘agalmatophilia’, from a Greek word for ‘statue’, and his book is less interested in dolls as toys than it is in replica humans – statues and waxworks and automata. He begins with Ovid’s story about Pygmalion, a rampant misogynist who has decided that women are immodest and unkind and has chosen to live alone. A sculptor by trade, he carves an ivory statue that looks just like a real girl, and even seems to return his kisses. He gives her presents, likes dressing her up and buying her jewellery and ribbons and ‘pet birds’ (no doubt caged); he takes her to bed with him on a regular basis. At the festival of Venus, he goes to the celebrations and implores the goddess of love to help him find a wife ‘just like my ivory girl’. His prayer is granted: that night when he lies down once more beside the statue, the ivory softens and warms at his touch: ‘It is a body!’

Ovid’s tone is customarily offhand, exposing the absurdity in Pygmalion’s behaviour, as well as hubris, since the sculptor’s work echoes the gods’ creation of man – and of Pandora, also perfect in every way. With his light-footed scepticism he is also calling on his readers to marvel at the contrary actions of a god like Venus. He doesn’t comment on the outcome of the miracle – did the couple live happily ever after? But the outlook is usually overcast in Ovid, and the next story is about Pygmalion and the living statue’s unhappy grandson, who inspires a furious passion in his own daughter, Myrrha, with catastrophic consequences. She is turned into the myrrh tree, weeping bitter, fragrant tears.

Pygmalion and Myrrha offer only two extreme instances of desire’s vagaries in Ovid’s vast and ironic catalogue of misdirected love (the poet is a kind of Kraft-Ebing avant la lettre). But the statue Pygmalion makes is unhoused in a different way from scores of other subjects of metamorphosis who change their outer form and become trees or plants or animals or stones, yet still retain their spirit, their unique personhood. The statue comes to life in an individual body; it looks like a person, but one whose interior can only be a ‘thing-soul’. This is Rilke’s coinage to get at the baffling character of dolls and toys. He sees how destructive the feelings they elicit are, however loving the playacting; how the dreams they inspire come up against indifference and can lead to damage. Baudelaire describes the frustration of a child at play, who ‘twists and turns the toy, scratches it, shakes it, bangs it against the wall, hurls it on the ground … But where is its soul??’

Whatever happened to Pygmalion and his unnamed creation after her startling change, the long tail of responses in Western culture have made her a figure of male desire fulfilled to perfection, the archetype of the living doll created by and for her maker to meet his every wish. Smith tracks Pygmalion and Galatea (as she is later called) into the murkier reaches of the sex trade and the fantasy companionate marriages of men with a ‘Dutch wife’, so called after the habits of lonely sailors in the Dutch navy. On the way, he looks at a whole eerie tribe of unhoused bodies: sacred statues rendered with startling naturalism, their wounds and tears lovingly reproduced; waxwork effigies and forensic teaching models in wax; the shop mannequins in surrealist aesthetics; the fetishised and monstrous apparitions of Duchamp and Bellmer. Specialist firms today supply figures in new materials that create the feel as well as the appearance of skin and hair, and offer every kind of intercourse, regulated as to orifice, temperature and constriction. At Bubble Baba, the white water rafting challenge that takes place in St Petersburg every year, the contestants use life-size sex dolls as lilos. (Pussy Riot, where are you?) However sad and horrifying the practices involved, they partake of the general troubling, creepy character of dolls.

The subtitle of The Erotic Doll is ‘A Modern Fetish’, with the emphasis on ‘modern’. Smith tries to stake out new territory; he’s aware that both Gaby Wood’s Living Dolls (2002) and Kenneth Gross’s The Dream of the Moving Statue (1992, reissued 2006) have explored this material with learning and verve, and tries hard to distinguish his approach. He insists that the dolls he has chosen to explore are not surrogates for someone or something absent or unobtainable, but are the thing itself: his band of lovers are having relationships with the dolls for their own sake, not using them as stand-ins. By this token, the ‘modern fetish’, as opposed to the old, superannuated version, is enough in itself, as a made thing, as artificial life in an age of intensified animism and blurred boundaries. In effect, it inverts the Pygmalion story.

Smith is eager to apply ‘Thing Theory’ to the animate and animated object in modernity, but he doesn’t quote some current thinkers who could have helped him to think things through: Sherry Turkle, for example, has written very shrewdly about the changed relations of people to things, to laptops, mobile phones and iPads – let alone virtual reality headsets. Computerisation has altered the character of inert matter: consciousness is smeared all over the waves and wires that connect us to one another and to ourselves.

This book is platypus-like, unclassifiable. The production is anachronistically unaustere: the coated paper smooth and fleshly, as if the designer had taken a cue from the book’s subjects, the design self-conscious (lower case, infra-thin, machinic sans serif font), and the publication enriched by an abundance of colour illustrations beyond the realm of the possible for most writers today. These sumptuous plates present many contemporary artists’ bizarre play with replicas and distortions: Allen Jones’s notorious S&M furniture from the 1960s, the Chapman brothers’ child gang bangs, Cindy Sherman’s lacerating self-portraits as victim of rape and murder, and other simulations, less naturalistic and doll-like, such as Louise Bourgeois’s lopped, scarred and sutured dummies posed in enigmatic scenes of family trauma. Smith aims to create a visual essay on the model of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas or John Berger’s celebrated montages in Ways of Seeing, but his album doesn’t yield meaning through thoughtful juxtaposition or surprising diachronic analogy; just bunching the pictures together, without a full discussion, leaches them of meaning, ignores the women artists’ critical and ironic fury, and reduces them to shocking pictures – sensationalism.

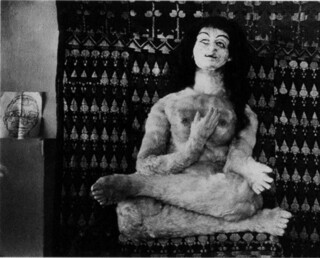

The arguments are hard to extract: I sometimes felt as if I were a long way down in a lightless mine hoping for a glint of the promised metal. Towards the start, Smith provides a flagrant case of i-doll-atry, where Oskar Kokoschka commissions a life-size replica of Alma Mahler. She had left him, and in 1918 he issued a professional dollmaker, Hermione Moos, with minute instructions couched in the language of forensic surgery, down to the last tuft: ‘Please make it possible,’ he wrote, ‘for the touch to enjoy these parts where fat or muscles suddenly give way to sinews, and where the bone penetrates to the surface, like the shin-bone.’ He wanted especially to re-enact his passion through touch: ‘Often hands and fingertips see more than eyes.’ The result was weird, very weird, since Moos decided to make her doll furry all over like one of the sweet satyr women from a medieval tapestry, though much heftier. She looked, someone remarked, like an old polar bear.

Smith tells us a great deal about the doll’s subsequent fate, though confusion reigns over the gory and/or pathetic details. Somehow it ends up trashed in the back garden, just as in one of Cindy Sherman’s mises-en-scène, or like one of those soft toys dustmen impale on the squalid prow of their grinding garbage trucks. Smith is determined to bring this life-size dummy Alma to the stand in defence of his conviction that ‘Kokoschka does not substitute a fetish for reality; the overvalued fetish is the thing the attachment to which structures what man’s desire is. As such the doll is a thing, a thing that things, shapes and transforms man’s understanding of his erotic attachment to such form or forms, the itinerary of his own desire and, ultimately, himself.’ But this doesn’t convince: surely this shameful, sad and ludicrous hairy doll was ‘letting [itself] be dreamed’ into the lost beloved that was Alma Mahler; it was acting as a transitional object, in that most useful phrase of Winnicott’s about play as a means to separate from someone and learn to live with oneself. (The person with whom Kokoschka seems truly to be having a relationship is the dollmaker; he writes letter after letter to Moos, with drawings and details of an intimate, arousing sort. She was a willing and imaginative co-fetishist in Kokoschka’s scheme, but we don’t hear her words or learn more about her.)

‘I do not like Surrealism, never have, never will,’ Smith announces. ‘It is the disease whose cure it purports to be.’ Smith is the director of research in the School of Humanities at the Royal College of Art and the founder and editor of a high-end theoretical showcase, the Journal of Visual Culture; no doubt he battles on a daily basis with wide-eyed fans of Surrealism among his students and colleagues, and so wants to make his statement once and for all. But disavowing your principal subjects has a stifling effect on the reader, and the many pages that follow about Surrealist exhibitions, fetishism and Marcel Duchamp’s overpraised and over-expounded peepshow Etant donnés give the lie to his bold rejection of the movement.

Somewhere along the slow descent into the mine a different book was left behind. Smith admits confusion about i-doll-atry – is it a perversion at all? he asks. Polymorphous perversity is a defining human feature; is it perhaps even a right? He doesn’t broach the meanings of child’s play or the continuity between adult fixation on dolls and their child selves (no mention of child psychologists, such as Marion Milner or Winnicott himself, and just one dismissive allusion to Melanie Klein). Yet he goes on to ask himself why, if nobody is harmed by fetishistic play, he feels that the makers of these sex dolls are right to refrain from making figures of children. His book skirts the whole question of child dolls and statues, even though the erotic uncanny hangs around them so sharply. The little boys and girls made out of plaster in the 1950s by Morton Bartlett, a Chicago loner who died in 1992, are mentioned in passing; these life-size replicas are among the most alarming and truly strange sculptures I’ve ever seen, in their exact fidelity to dress, anatomy, expression and gesture (they were shown, discreetly, in the Hayward Gallery’s exhibition last year of outsider art, The Alternative Guide to the Universe). Bartlett called his creations ‘sweethearts’ but the boys look like him at the age of eight when both his parents died.

Bartlett photographed his effigies, using strongly atmospheric lighting to render shadow falling on a sleeping child’s face or the tears springing from a little girl’s eyes. In 1963 he published the images in Yankee Magazine, and they must have looked less creepy in that context: he seems, at least, to have raised no alarm. After this, he never went back to his ‘hobby’. He had, however, understood something about the modern uncanny: its relationship to photography and cinema. In the post-Freudian universe, E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Olympia, the object of desire in his story ‘The Sandman’, has enjoyed a potent afterlife in the cinema, replacing Pygmalion’s Galatea as the dominant type of uncanny automaton, a vacant, eerily smiling, walking, talking, living, singing doll.

The photographed doll is a copy of a copy and as such it can ratchet up the effect of uncanny lifelikeness: the contented husbands of ‘Dutch wives’ stage tableaux of their domestic bliss for the camera, in a Facebook realm of the unreal real. In contrast to this, Giorgio Agamben points out in ‘The Eternal Return and the Paradox of Passion’ that the word ‘likeness’ has the same root as the German word for ‘corpse’ (Leiche), and suggests that this arises through a classical concept of the eternal image: in the afterlife our phantom selves resemble us unerringly and completely. The camera can also capture this ghostly emptiness and plunge the viewer into ‘the uncanny valley’, so-called by animators to describe the mortician effect that too much verisimilitude produces. Accordingly, a doll so real she could be alive tends also to look dead.

Back in the 1970s, the art historian and curator Jasia Reichardt put together a brilliant anthology of automata, androids, cyborgs and other dream-machine women (and men) in her book Robots: Fact, Fiction and Prediction. New Eves and dream wives assembled from machine parts or other inert matter (the Bride of Frankenstein, the armoured idol Maria from Metropolis) come to life persuasively on the screen, as cinema is itself a machine with light and shadow as its animating tools. Reichardt has fun with her subject in ways Smith, snarled up in the nasty implications of so much of his material, doesn’t attempt. She introduces a splendid erotic doll into her pantheon: the ‘femfatalatron’. Devised by a great inventor to rescue Prince Pantagoon from horrible Pangs of Love, ‘the femfatalatron is an erotifying device, stochastic, elastic and orgiastic, and with plenty of feedback; whoever was placed inside the apparatus instantaneously experienced all the charms, lures, wiles, winks and witchery of all the fairer sex in the universe at once. The femfatalatron operated on a power of forty megamors … while the system’s libidinous lubricity, measured of course in kilocupids, produced up to six units for every remote-control caress.’ But this ultimate sex doll machine fails to cure the prince, who ‘emerges from it pale, faint and with the name of his beloved on his lips’. The femfatalatron was originally imagined by Stanislaw Lem in a story from The Cyberiad, published in 1967 in Krakow – in times when, as in Baudelaire’s, entertainments could seem innocent.

Pygmalionist attempts to re-create the dream of a perfect partner have intensified with the coming of digital and cybernetic technologies and their extraordinary powers of reproduction and animation; animators keep refining their techniques in order to conceal their use. The author of The Erotic Doll must be cursing his bad luck that he finished his book before the current show at the Hayward Gallery, The Human Factor (until 7 September). Selected by Ralph Rugoff with his usual delight in contemporary artists’ waywardness, the figures here take the questions Smith is exploring to another level of enigma and intensity, to reveal that infusing a body with enargeia, the quality of vivid lifelikeness which was a Greek ideal, can result in extreme degrees of estrangement. As at Madame Tussaud’s, The Human Factor unfolds an unsettling spectacle of still life, ranging from body casts of poignant physical delicacy (Ugo Rondinone’s young dancers resting) to disfigured bomb victims, as in Thomas Hirschhorn’s Resistance Subjecter (2011), which displays shop window mannequins in a glass box; their blasted insides sprout spars of crystals, mineral wounds which speak bitterly against the soft porn of their erotic doll-like state.

In another room Paul McCarthy has directed Hollywood special effects technicians in his hometown of Los Angeles to create a nature morte of truly unsettling naturalism: That Girl (T.G. Awake) places three effigies of a model casually sitting on a plinth with her legs parted as if in a studio pose. The skill of the simulation is consummate; no dip into the uncanny valley occurs, partly, I think, because the artist has made T.G.’s vulva the fulcrum of her pose and the irresistible focus of our gaze. McCarthy has a long record of messing with sacred and profane themes and transgressive child’s play with food and dirt. Here he’s rendered the female form divine, not symbolised by the Virgin Mary or the yoni of a goddess, but embodied in an ordinary young woman. Beside her statues, T.G. appears on a monitor, filmed rocking to and fro on her plinth, throwing her head back and uttering wordless, low-volume howls – as if struggling back into language, that sign of the human.

I had a doll that used to cry ‘Mamma’ when you turned her over and the effect was very powerful and wonderful, until her voice box, located in her tummy, fell out. Her inner workings were visible and comprehensible, yet to me she was as uncanny as Olympia; now, by contrast, the technological uncanny defeats understanding. I could swear I saw That Girl blink as the light caught her liquid, lash-fringed eyes, and I felt for the guard who has to stay there in the room, making sure nobody tries to see if she’s warm.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.