I had the daily pleasure of seeing the west wing of the Glasgow School of Art, with its castle-like stonework and triple tall oriels rising dramatically from the steep slope of Scott Street, when, for more than a decade, I taught architectural history at the Mackintosh School of Architecture. I also had the privilege of being able to explore the interior of the School of Art at will. And I became more and more impressed. It was a building that worked, though made of ordinary and traditional materials – stone, timber and iron – on a limited budget; it was the product of a mind at once practical and imaginative. Throughout, as my then boss, Andy MacMillan, put it, Mackintosh ‘demonstrates a creative exploitation of each and every specific requirement, seizing the opportunity to create an architectural “event” through some feat of invention’.

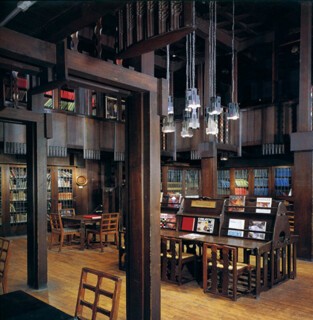

The thought of any part of the GSA being damaged is terrible, but that it was the library that was destroyed really is heartbreaking, for it was Mackintosh’s finest, most personal and most mysterious creation, a complex space, at once dark and well-lit, in which every detail was personal and deliberate. It was the summation of his desire to combine structure and decoration, to create powerful spaces, to make something new out of history and tradition and to explore the potential of symbolic forms. The management of the GSA, which, despite warnings about fire, allowed a student to combine expanding foam with a hot projector in the basement, now cheerfully assure us that most of the building is safe and that the library can be re-created as it is so well documented. Perhaps: but the possibility of examining the original woodwork and of experiencing the tangible result of the designer’s close involvement has gone – along with the precious books that the room contained (plus the paintings and more than a hundred pieces of Mackintosh furniture in store in the room above).

As I learned to admire Mackintosh’s work, I also became increasingly exasperated by the Mackintosh myth: that he was a lone misunderstood genius, Scotland’s answer to Van Gogh, a progressive, forward-looking artist who was not appreciated by his contemporaries in Britain and who died, unsung, in exile. In trying to understand the historical Mackintosh, we have to deal both with the commercialisation of his legacy – the ‘Mockin’tosh’, as Murray Grigor termed it, that fills the shops – and the tendency to see him as a lone figure instead of a man who, like all great artists, did not just borrow but stole, from others and from the past. I used to wonder what all those visitors in the grip of the Cult of Mackintosh, exposing endless reels of film as they gazed at the dark brown sandstone of the Renfrew Street front, really made of the building. Glasgow may be on the pilgrimage route along with Barcelona, Budapest, Nancy, Moscow and Riga, those cities in which strikingly original buildings from the years around 1900 can be found, whether Art Nouveau, Jugendstil or Modernismo, but the GSA building is not wildly unconventional in either mass or detail, as the creations of Gaudí are, or made conspicuously eccentric by the use of strange organic curvilinear forms, as are those of Guimard in Paris or Horta in Brussels. The main front of the School of Art has the scale of, and is built like, a Glasgow tenement; it has a cornice, and there are pediments – traditional elements, even though metamorphosed by an unusual sensibility.

A competition for the design of a new building for the School of Art was held in 1896 and won by the Glasgow firm of Honeyman & Keppie. The drawings were made by a brilliant young assistant, a policeman’s son from Dennistoun who was born Charles R. McIntosh, but he was not at first given any credit for the design. The plan is admirably clear, with tall north-facing studios placed along spinal corridors. The huge windows that light these studios may well have been inspired by those at Montacute in Somerset, the Elizabethan country house which Mackintosh had sketched. As for other details, architectural historians can enjoy themselves spotting the sources, mostly from recent progressive English buildings by Voysey or Norman Shaw (a London Scot), and some Scottish ones, by the Glaswegian J.J. Burnet. One influence behind the vaguely Scottish Baronial east elevation in Dalhousie Street is the little-known James MacLaren, a gifted Scottish architect who died young. Mackintosh loved castles, and the extraordinary harled irregular south elevation that rises from the building line on steeply sloping ground overlooking the rooftops of Sauchiehall Street might be Fyvie in Aberdeenshire, as drawn by Jessie M. King.

For there is another character evident, one which so many of the visitors come to see: the sensuous, decorative excitement of the Art Nouveau. It is there in the treatment of the metalwork, in the tapering timber columns of the central first floor museum, in the treatment of the little leaded-glass windows in the doors and, above all, in the white-painted woodwork of the board room, ornamented with gentle curves cut in relief. Mackintosh was an artist as well as an architect. With his future wife, Margaret Macdonald, her sister Frances and her future husband, Herbert McNair, he was one of ‘The Four’, responsible for paintings of attenuated female figures with intense faces, and stylised curvilinear decorative swirls. To their critics, their work was the ‘Spook School’. It was for such work, and for their distinctive interior designs and furniture, that Mackintosh, together with Margaret, first became known abroad and invited to exhibit in Vienna, Turin and Budapest.

At first the School of Art could only afford to build the east wing and the central entrance bay. By 1907, when enough money had been raised to complete the building, the architect had matured, having designed several houses and tea rooms for Kate Cranston, and was now a partner in the firm of Honeyman, Keppie & Mackintosh. By this date, the international Art Nouveau had gone off the boil and Mackintosh, exploring a new decorative manner, responded both to the contemporary revival of Classicism and to the more formal, geometrical style developing in Vienna. So, while completing the original scheme for the main façade, he completely redesigned the rest of the west wing with its library. The dramatic west front, with its towering oriels, is an abstracted Tudor composition which, as John Summerson pointed out, may owe something to the central reference library in Bristol designed by a distinguished but less applauded English near contemporary, Charles Holden. But there was no precedent for the extraordinary library space behind those tall metal oriels.

The library was at once very practical and very strange. Made entirely of dark timber, it was dominated by tall square piers rising from floor to ceiling which supported the balcony running around the room on all four sides. The piers were placed far in front so as to be conspicuous. Was the idea of a Forest of Knowledge in Mackintosh’s mind, in which symbolism was so important? Oddest, and most personal of all, were the timber pendants on the balcony front, each with what might be hanging tassels, but with little ovals, like bubbles, in the gaps. Each one was slightly different. Of this mysterious, enchanting room Summerson wrote that

one has the odd feeling that if the whole room were turned upside-down, so that the light fittings grew upwards from the floor, it would be even more true to itself. Here we are in a private world – a world where, as in Beardsley’s drawings, we tread with fascinated horror, unbounded admiration and a sense of being total and probably unwanted strangers.

This room is now ashes, but it is proposed to reconstruct it faithfully. How perverse that the sort of modernists who disapprove of replicas of Georgian interiors, such as the National Trust had done after the Uppark fire, preferring something new, of our own time, should favour the building of an archaeological pastiche, even to the extent of recommending that the new wood is patinated to look old. Such is the reverence now granted to this much misunderstood designer.

It might seem remarkable that Mackintosh ever got away with the west wing: he had the school governors breathing down his neck insisting on economy. It was probably only the support of the director, the painter Francis Newbery (an Englishman), that made it possible. Worse, the architectural climate in Glasgow was changing. Since 1904 the head of the School of Architecture had been a Beaux-Arts trained Frenchman, Eugène Bourdon, who was strongly opposed to the ‘New Art’ and interested in modern American Classical architecture. Bourdon’s students poked fun at the new west wing, mocking Mackintosh’s decorative system of ‘permutations and combinations of simple forms’ in which ‘once the motive is selected an office boy or a trained cat can do the rest …’ Having been a brilliant student himself and treated as a prodigy at an early age, feted abroad and possessing no little personal vanity, Mackintosh must have found it intolerable to have lost touch with the younger generation and to be patronised by student critics. Perhaps it was this, rather than the continuing hostility of older architects like Burnet, which suggested to him that there was little future in Glasgow for his sort of architecture.

After the completion of the School of Art building in 1909, Mackintosh’s career went downhill. Drink and depression increasingly dominated his life. Less and less productive, he left the practice in 1913 and Glasgow and Scotland the following year, ending up in Chelsea. He had one more, limited, opportunity to build when, during the Great War, an engineer and manufacturer of model trains, Wenman Bassett-Lowke, asked him to remodel the interior of his Georgian terraced house in Northampton. After that, Mackintosh and Margaret moved to the South of France where he devoted himself to painting, producing many of his powerful, sophisticated watercolours in which landscapes look like solid architecture. He returned to London to die, horribly, of cancer of the tongue in 1928.

It is not true that Mackintosh was then completely forgotten. Illustrations of the west wing of the GSA appeared in 1924 in Modern English Architecture by Charles Marriott, art critic of the Times, who thought that ‘it is hardly too much to say that the whole modernist movement in European architecture derives from him; and the Glasgow School of Art, as an early and successful attempt to get architecture out of building, making decorative features out of structural forms, goes far to explain the reason why.’ In 1933, reviewing the Mackintosh memorial exhibition in Glasgow, P. Morton Shand, critic, oenophile and the grandfather of the Duchess of Cornwall, wrote in the Architectural Review that ‘he has been called “the father of modern architecture”.’ In 1936, in the first edition of his Pioneers of the Modern Movement, Nikolaus Pevsner wrote that in Glasgow ‘there worked one of the most imaginative and brilliant of all young European architects, and at the same time one of the originators of the Art Nouveau’, adding that Mackintosh’s later work showed him ‘as the one real forerunner of Le Corbusier’. And the following year, in an essay in the catalogue published by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Henry-Russell Hitchcock also included pictures of the GSA and claimed that ‘no work of British architecture could more appropriately serve as an introduction to an exhibition of Modern Architecture in England.’

The tendency to see Mackintosh primarily as a pioneer of modernism culminated in the publication in 1952 of a biography by the English architect Thomas Howarth, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement. But to interpret his work in this light required a certain manipulation of the evidence. Shand, and others, deplored the feminine, decorative influence of Margaret’s ‘rather thin Aubrey Beardsley mannerism of the arty-crafty type’ on Mackintosh’s purely architectural development. Yet, shortly before he died, the man himself wrote from France asking his wife, to whom he was devoted, to ‘remember that in all my architectural efforts you have been half if not three-quarters in them,’ and once said that ‘Margaret has genius, I have only talent.’ As Alan Crawford concluded in his sane and succinct 1995 study: ‘Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald came together not only as man and woman, but also as artists. From this point on, the story of Mackintosh’s life, and of his work, cannot be told as if he were a single person.’

A more balanced interpretation of Mackintosh came with the publication in 1968 of a study by the Canadian-born architect Robert Macleod, who concluded that he was ‘a last and remote efflorescence of a vital British tradition which reached back to Pugin … With his pursuit of the “modern”, his love of the old, and his obsessive individuality, he was one of the last and one of the greatest of the Victorians.’ This remains a truth that neither modern architects, nor the authorities in Glasgow, wish to hear.

The year 1968 was, among other things, the centenary of Mackintosh’s birth: an ambitious exhibition was duly arranged by the Scottish Arts Council. It was hosted at the Edinburgh Festival and in London, at the Victoria & Albert Museum; a reduced version travelled to several European cities. But it never got to Glasgow. The city’s attitude to its famous son is puzzling. Despite the rise in Mackintosh’s reputation, Glasgow contrived to plan urban motorways which threatened both his Martyrs’ and Scotland Street Schools. In 1950, the Corporation had been encouraged to buy the lease of the Ingram Street Tea Rooms with its varied set of interiors designed for Kate Cranston which, had it survived, would now be a lucrative asset to the city. But in 1971 it dismantled the interiors, with much of Mackintosh’s work being subsequently damaged or lost. Earlier, Glasgow University had demolished the Mackintoshes’ home in Hillhead, although the ethereal white interiors were saved by Andrew Maclaren Young, organiser of the 1968 exhibition and a hero in this sad story. They were eventually reconstructed in a concrete annex to the new Hunterian Museum building.

When Murray Grigor, who made a film about Mackintosh in 1968 and soon after co-founded the Friends of Toshie in emulation of the Amigos de Gaudí in Barcelona, asked people in George Square who they thought the man was, ‘the answers went from the inventor of raincoats to toffees, but few knew the architect.’ The local attitude to Mackintosh had long been one of ignorance or active hostility. Maclaren Young thought the latter was a form of ‘queer-bashing’. The much reproduced photograph by Annan – ‘loose collar and a tie gathered in a big, mock-careless bow, like W.B. Yeats’ – says it all. He also had airs, and it cannot have helped when he and his half-English middle-class wife moved to that introverted, artistic house in the West End.

Most of Mackintosh’s buildings survived, but it was outside opinion that was largely responsible for saving them and reviving interest in his work. The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was founded in 1973 and soon had an international membership. At the same time Cassina, in Italy, began to manufacture reproductions of Mackintosh’s strange, tall, elegant furniture. By the 1980s, his status as a great architect and designer seemed secure and its unfortunate concomitant, the Mockin’tosh industry, was flourishing, giving rise to the impression that poor Toshie was a designer of tea-towels, mugs and greeting cards based on, to quote Grigor again, ‘misunderstood typography along with wilting roses, four-squares, or whatever happened to take their fancy in Mackintosh’s diverse decorative output’. It was around this time that a semi-mythical character entered the wider public consciousness: ‘Rennie Mackintosh’ – an appellation he never used or was known by.

Tourist tat can be taken or left, but other well-meant tributes to Mackintosh were surely misconceived. Visitors to Glasgow today are directed to the House of an Art-Lover in Bellahouston Park as if it were an authentic work by Mackintosh. It is not. This curious case of necrophilia, on which work began in 1989, is the necessarily fudged realisation of the exquisite drawings which Mackintosh and his wife entered for a competition announced in Darmstadt in 1900. They were given a special prize; the winner was an Englishman, M.H. Baillie Scott. It is hard to believe that Mackintosh would ever have built this Fin-de-Siècle dream without a lot of revision. As it is, without the master’s guidance, the pseudo-Mackintosh details have a kitsch quality which bodes ill for any reconstruction of the Glasgow School of Art’s west wing.

Amid all the misunderstandings and appropriations, Mackintosh’s masterpiece on the top of Garnethill stood out as tough and authentic, a working building in which his rare command of light and spatial effects was enlivened by his delight in detail and decoration. But even this triumph had to suffer insults. The latest was only completed this year: the Reid Building, named after the last director of the School of Art. This replaced the unsympathetic Brutalist tower, named after Newbery, which the Mackintosh successor firm, Keppie Henderson, designed in the late 1960s, along with another, lower, bush-hammered concrete block, equally inappropriately named after Bourdon, slung over Renfrew Street to impede the view of the west wing.

The Reid Building, of reinforced concrete clad in pale green glass, massively fireproof and, at £50 million, massively expensive, was designed by the New York architect Steven Holl, who wishes ‘to realise space with strong phenomenal properties while elevating architecture to a level of thought’. Like all architects, he professes immense respect for Mackintosh and claims that his building creates ‘a symbiotic relation with Mackintosh in which each structure heightens the integral qualities of the other’. In fact, as vociferous critics from outside Glasgow soon noted, it overawes Toshie’s carefully crafted masterpiece on the opposite side of Renfrew Street while failing to provide a congenial environment externally or internally. Until the fire, it was the final insult.

Culpably arrogant as it is, the new Reid Building has a wider, disturbing significance in view of the forthcoming referendum on Scotland’s independence, a context in which the mythical Mackintosh is celebrated as a Celtic hero whose School of Art is a symbol of Scottish talent and creativity; also a context in which governments in Westminster and Edinburgh are happy to offer unlimited sums to restore his ‘priceless gem’ (a generosity not extended to the threatened works of Glasgow’s other great 19th-century architect of international stature, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson). The real Mackintosh flourished when Glasgow flourished as the Second City of the Empire, with a civic culture that was as British as much as it was Scottish. To build its new home, an economical ‘plain building’, the School of Art commissioned a good local firm, and the assistant entrusted with the design eventually emerged as a distinct local talent. Just over a century later, the School of Art, in search of a new ‘icon’, held another competition but this time it was determined to select an international superstar architect. Any local genius who’d recently emerged from the Mackintosh School of Architecture was denied the opportunity to show what he or she could do. All this suggests to me that Glasgow, far from gaining confidence in recent decades, has lost it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.