At the Pompidou Centre in Paris, a two-hour wait will get you ‘priority access’ to the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition. It’s available only to friends of the museum, members of the press, and those who bought tickets in advance and naively thought they’d walk straight in. As the American woman behind me remarked, it’s the kind of queue that would be generated in the US by the opening weekend of Terminator 4. The show is well worth it. But once you’re in Paris, taking in the blockbuster effect and the tidal waves of press devoted to ‘the master’, with his ‘genius’ and his ‘magical moments’, you can’t help thinking about the easy sort of patriotism Cartier-Bresson now elicits: he’s French, he’s familiar, he soaked up a century and worked in a medium that lends itself to fridge magnets. Of course, if we have become blasé about photography’s reach – in the world and into our homes – then Cartier-Bresson, art photographer, photojournalist and co-founder of the Magnum picture agency, is among those we have to thank. But still: ten years after his death, how should his work be understood? The curators have answered that question by claiming to break down the received view: his life, travels and allegiances are conceived as a whole, and the greatest hits – the so-called ‘decisive moments’ – are complemented by other work.

His early imitations of Eugène Atget, and his attempts when in Africa to be more like the great Hungarian Martin Munkácsi, were unpromising. Then came Surrealism – or an attempt at it. A curtain wrapped around a head, a shirt hanging upside down on a washing line like a ghost, animal entrails arranged into abstractions: photography, for those who take a principled stand against the manipulation of images, is just not that surreal. While he hovered around the edges of the group – worshipping André Breton, befriending René Crevel, looking up to Max Ernst – he preferred their talk of revolution to any art they made, and never said a word at their gatherings. His photographs from that time feel as timid as he professed to be in their company. He was under no illusions about some of the early phases of his career. His Ivory Coast pictures came back damp and fogged, he later wrote; and as for the Atget-like shop-fronts, he never got the hang of that large format camera anyway. His prints – as the exhibition confirms – were poor and Pierre Assouline’s 2001 biography is full of gallery people saying so at the time. The photographer later joked that friends referred to him as a ‘foutugraphe’, given the likelihood that he would screw things up.

Although he was given a camera (‘un Brownie-box’) at the age of 14 or 15, he was not an instant convert to the medium. Born in 1908, he didn’t really start taking pictures until he was twenty, and was, even then, largely uninterested in anything technical. He mainly wanted to paint. From the point of view of his family – industrialists, château-owners, and the extremely wealthy manufacturers of Cartier-Bresson sewing thread – that was bad enough. But he turned out to be so lacking in painterly flair that Gertrude Stein, in her un-Delphic way, told him not to give up the day job – he would do well to join the family business. (Some of his early canvases have been included in the show to prove her point.) Though he switched to photography, he always said he was more influenced by painting and cinema – ‘I owe nothing to photography,’ he claimed, looking back – and at various points in his life gave up taking pictures for years at a time.

But when he bought a Leica in 1932 he became a purist in its service. He tended to stick to three fixed lenses (35mm, 50mm and 135mm), and was adamant that cropping of any kind was an admission of defeat. In the same year, equipped in this way, he produced two of his most famous photographs: the cyclist caught gliding down a cobbled hill at the base of some stone steps in Hyères, and the man jumping over a puddle behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, captured in mid-air and reflected perfectly in the water, the pitched roof of the station behind him shrouded in mist.

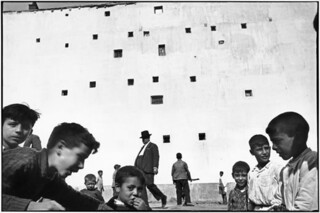

In 1933 he took some exceptional pictures in Spain: bright, human, swift. Many of them were organised against walls. Painted, dotted with tiny windows, pasted with posters or knocked through to make a jagged hole, the walls have a structuring effect on the final shot in much the same way that a backdrop in the theatre does. Over these plain, static grounds Cartier-Bresson presented people vibrantly: a group of boys playing in Madrid, one of them smiling to camera as a round, moustachioed man in a hat and suit rolls by behind them; a smart gentleman with a cane silhouetted against a white circle painted on a fence, as if in the final diminishing frame of a silent movie; a group of children clambering around rubble, one of them almost seeming to burst out of the photograph itself.

A year later he went to Mexico, where he hung out with Langston Hughes. It was a time of cultural prosperity, but Cartier-Bresson embraced the slums with the gusto of an aristocratic foreigner, capturing picturesque prostitutes and taking endless shots of dusty people unable to get up off the pavement. I may be alone in disliking this series. At any rate, Cartier-Bresson’s various visits to Mexico were considered fruitful enough to merit a discrete volume (Mexican Notebooks, 1995). But compared to the work of Mexican photographers – Manuel and Lola Álvarez Bravo, for instance, or the adopted Mexican Tina Modotti – there is a sort of ethno-prurience about them. Men and women asleep, on the street, in rags; children crying, in a crowd, in rags; dark-skinned boys frolicking naked on the cracked earth; girls with plaits selling fruit. The compositions are cluttered, the grey tones undifferentiated; the photographs exist only to show these curious people in their uncivilised habitat. As Assouline put it (perhaps intending only to describe Cartier-Bresson’s love of the country), ‘Having once been an African hunter, he would now become a Mexican photographer.’

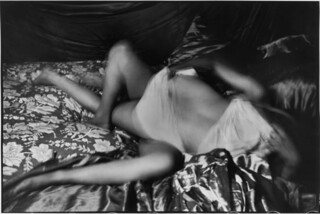

One photograph stands out. It’s so alive it barely belongs in the company of the others – or indeed in the company of any of Cartier-Bresson’s work, though it’s among his best known. Dubbed ‘The Spider of Love’ by his friend André Pieyre de Mandiargues, it shows a couple in a heated embrace on a bed; or rather, three legs, an arm, a hand, a lower back and some indeterminate muslin-weight clothing in the process of being peeled off. The triumph of the photograph is that it’s both explicit and mysterious, intimate yet almost abstract: how, you wonder, are its subjects entwined? Which way up are they? Are they men or women or one of each? The edges of the limbs are blurry from the action, and a little dream-like as a result. The image shows heat and movement above anything else – although you can’t see these people’s faces, you can almost feel their skin. Assouline explains that Cartier-Bresson was at a house party in Mexico City, turning down tequila because he was ill. He wandered around the house out of boredom, and pushed open a door to find that ‘two lesbians were making love.’ The friend he was with picked up a lamp so he could photograph the scene. ‘I was very lucky,’ Cartier-Bresson later said. It’s unfair to allow the method to detract from the result, but the story gives us an early clue: the voyeuristic circumstances are in keeping with what would be a cool, and lifelong, observational stance.

When he returned to France, Cartier-Bresson tried to work in the cinema, but both Buñuel and Pabst turned him down. Jean Renoir, however, took him under his wing and Cartier-Bresson assisted him until events in Spain forced him to take up his Leica again in 1936. He didn’t cover the Spanish Civil War but he joined the Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers in Paris, and felt photographers had to be more engaged. Some time around then, a woman in the street asked him whether he was a journalist. He didn’t know what to say – he’d been so inconsistent, and so ambivalent, about photography. Eventually, he replied: ‘I’m just a maniac.’

When did Cartier-Bresson work out what he wanted the camera to do? Was it a political tool that could show reality on behalf of the Popular Front; or an art form that sidled up to Surrealism and proved reality was never quite what it seemed? It would have been hard for anyone, given the political and artistic prerogatives of the period, to reconcile the two. But in 1936 it seemed to others that what he had been doing as he recorded the small gestures of humanity in the street was preferable to the schematised wit of a studio. That year Louis Aragon, who headed up the revolutionary association Cartier-Bresson had joined, and got him a staff job on the new left-wing paper Ce Soir, contrasted his images with those of Man Ray. Aragon was one of the founders of Surrealism, and had collaborated with Man Ray; but the sort of playfulness that imposed a violin’s f-holes on a woman’s Ingres-like back could only really flourish, in Aragon’s view, in times of prosperity. Cartier-Bresson’s work, so hopeful of surrealist status but so helplessly rooted in realism, became a kind of call to arms. ‘This art,’ Aragon said, ‘is the art of the period of wars and revolutions in which we are living at the moment, when its rhythm is quickening’.

Other moments can be seen as turning points in that new, journalistic direction, though Cartier-Bresson claimed to have been influenced by Surrealism all his life. There was the time, in 1940, when he buried his camera in a farmyard in the Vosges, cut up his negatives and kept only his favourites, sending them in a biscuit tin to his father for safekeeping. There were the three years he spent in the Black Forest as a prisoner of war, and the attempts he made to escape. (The third was successful.) There was the aftermath of occupation, and the Liberation he recorded as a sequence of razed buildings, wrecked lives and ghostly rooms. In 1947, two things happened: the Museum of Modern Art in New York put on a solo exhibition of his work, and he founded Magnum with three others: Robert Capa, David Seymour (known as ‘Chim’) and George Rodger. When he saw his friend’s show in New York, Capa advised Cartier-Bresson to be cautious. ‘You will be labelled the little surrealist photographer,’ he wrote: ‘you will be lost, and will become precious and mannered. Continue on your way, but with the label of photojournalist, and keep the rest deep in your heart.’ In retrospect this, too, has the dramatic force of a turning point.

Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, who curated the MoMA show, began their research on the understanding that the show would be posthumous: they’d heard that Cartier-Bresson had died in the prison camp, or possibly that he’d been shot while trying to escape. In any case he couldn’t be traced, and although he did eventually surface and help them when the exhibition opened, much was made of the suggestion that he’d put in an appearance at his own funeral. The joke was telling and the show was more of a retrospective than anyone could have guessed, marking the end of Cartier-Bresson’s work in that artful vein. From then on, he was firmly of the world – bringing news, bearing witness. He’d taken Capa’s words to heart.

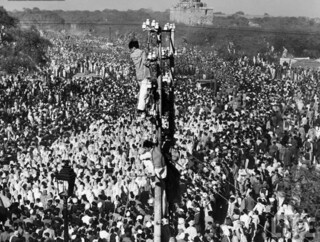

Cartier-Bresson was a tireless traveller. It’s not clear that he was any more courageous than that, but perhaps he didn’t need to be; he visited places that mattered. He documented Gandhi’s funeral, and the last days of Chiang Kai-shek. He went to Moscow after Stalin died, and then to Cuba, where he met Castro, and described him as having ‘the neck of a minotaur, the conviction of a messiah’. In Cuba he shyly took photos of beautiful women from behind. In Russia, India and China he liked the look of crowds. He never seemed to get very close. For a man whose photojournalism began in the 1930s, propelled by ideas of political engagement, he was markedly uninvolved. This is the part of his life that is considered trailblazing, but he may have made a greater contribution as a godfather than as a journalist. What he did for fellow reporters in founding Magnum is arguably more significant than any images he shot himself. He always looked up to Capa in matters of photojournalism, although – perhaps because – Capa was much less sensible, and younger than him. If Capa hadn’t been killed by a landmine in Indochina, the Cartier-Bresson aesthetic might not have become so dominant.

What exactly is a ‘decisive moment’? For the epigraph to his first book, Images à la sauvette (1952), Cartier-Bresson borrowed the phrase from the memoirs of the 17th-century Cardinal de Retz (‘There is nothing in the world without its decisive moment’). When the book was translated into English, it was called The Decisive Moment. The two titles could hardly have been more different, the French suggesting the gleeful, furtive takings of a man on the run and the English version implying a haughty academic precision. But the idea – if it is an idea – made him a legend: critics rarely fail to mention it; journalists always asked him about it. On one of those occasions, he just gave up. Referring the interviewer to the cardinal, he said: ‘It’s got nothing to do with me!’

Cartier-Bresson did try to elaborate, explaining how he set up his shot, then lay in wait for something interesting to cross into the frame. He criticised photographers who used cameras with motors, like machine guns, mindlessly targeting their subjects and never choosing anything exact. But when other people use ‘the decisive moment’ in their appreciation of his work, they tend to mean that he chose the ‘right’ moments, and this, I think, is the worst of his legacy. In the introductory essay to Images à la sauvette, he wrote that ‘instinctively fix[ing] a geometric pattern’ was key. Near the end of his life, he said he had sought to record ‘the emotion of the subject … that is, a geometry awakened by what’s offered’, as if emotion and geometry were the same thing. He was not a constructivist and was by now no longer a surrealist manqué; he was a realist. Nonetheless, for many years what he chose to record of reality was pattern: the texture of a wall, the twist of a staircase, the reflection in a puddle. He spoke often about his pursuit of the ‘golden section’ and implied that the best pictures could be judged with a ruler, or at least diagrammatically. The reason his photographs often feel numbly impersonal now is not just that they are familiar. It’s that they’re so coolly composed, so infernally correct that there’s nothing raw about them, and you find yourself thinking: would it not be more interesting if his moments were a little less decisive?

One way to trace the history of photography in the 20th century would be to look at the forking paths of two well-heeled Frenchmen who worked through most of it. There was Cartier-Bresson, who lived until 2004 and was dubbed ‘the eye of the century’, and there was Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986), whose work was compiled by Richard Avedon in his monograph, Diary of a Century. Cartier-Bresson travelled and recorded what he saw among strangers; Lartigue documented, exclusively and constantly, his own immediate circle. One was the father of photojournalism, a man who fought for reporters to retain rights over their material and so professionalised the medium; the other was the founder of the snapshot, an amateur par excellence whose habits foreshadowed the iPhone. Cartier-Bresson’s descendants, in this family tree, would be virtually every photojournalist since: Susan Meiselas, Steve McCurry, Gilles Peress, to name a few. Lartigue’s relatives would include not only photographers like Sally Mann, who portray their own children, but those like Nan Goldin who have rendered an immediate circle as if it were a family, or even photographers who have drawn on that idiom to make the foreign feel familial (Lucas Foglia in the American South; Jordi Ruiz Cirera in Mennonite Bolivia).

On the face of it, the man who roamed the world and defended the masses would seem to be the more admirable of the two, but I wonder whether the photographer who showed a world from within, and depicted the collapse of his own life (the departing lovers and the doomed ménages à trois) wasn’t braver.

Cartier-Bresson said his Leica could be ‘like a passionate kiss. But also like a gunshot or a psychoanalyst’s couch.’ He also claimed that the purpose of the portraitist was to get between the subject’s ‘shirt and his skin’. And he advised photographers to behave as though they were themselves ‘light-sensitive plates’. Where are the Cartier-Bresson photographs that show any of this?

Cartier-Bresson was famously impatient and, according to Assouline, could be imperious. He spent a good deal of time sculpting his own canon from the total Cartier-Bresson oeuvre, leaving curators with an artist-as-dictator. First, there was a sort of portfolio he put together in order to show his work to Jean Renoir (he remembered this volume with great affection). Next came the brutal selection of negatives to be kept in the wartime biscuit tin. Then, in the early 1970s, when he had given up taking photos professionally and gone back to drawing, he selected 395 images that he believed constituted the core of his work, and had new prints made: complete sets were sent to select museums, including the V&A. The Pompidou curators are now free of this – Cartier-Bresson is no longer alive and his widow, the photographer Martine Franck, died two years ago – but for the most part they have been guided by the legacy of his taste.

There is a different Cartier-Bresson hiding in this exhibition. A lightbox in a corner of a far room contains a slideshow of colour transparencies from the 1950s; they are a revelation of balance and intensity, yet treated as mere curiosities in the accompanying book, bunched together in their mounts, as if Cartier-Bresson’s handwriting on them were more interesting than the pictures themselves. It’s true that he never liked his own colour shots: he took them for money, because that was what magazines had begun to want. It’s also true that colour film speeds were slow in those days (not ideal for a photographer who liked to catch things on the move) and the tones exaggerated (hopeless for a man wedded to varieties of grey). Yet regardless of what he thought – and what Cartier-Bresson purists still think – he clearly had a feeling for colour. A man leaning on a boat on a beach in Portugal, the curves of its wooden frame reflecting those of his body, shows him producing soft, complementary shades. Diagonal shots of streets in Paris and London find him embracing saturated reds. New York is all yellow and black.

It’s very hard for photographers who look habitually for contrast and shape, with black and white reproductions in mind, to see colour in this way. Brassaï’s colour pictures, published a couple of years ago, were nothing like as good. Capa’s colour shots are strikingly different from Cartier-Bresson’s: in many cases you can feel Capa aiming for the most monochrome views, or at least not warming to what the film could do. Cartier-Bresson’s colour images show that in some respects, behind all the graphic rigour, he always had the eye of a painter.

The period of the Second World War – similarly restricted at Pompidou to one small room – has a kind of subliminal charge, a faint signal that something more than picture-taking was going on. It’s not what Cartier-Bresson would have called a decisive moment; if anything, it reveals him to be a little unmoored, investigating scenes around corners, keeping himself to himself. His haunting interiors, in an empty apartment on the avenue Foch just vacated by the Gestapo, are like film stills or photographs of crime scenes. The pages of an album put together from that period poignantly convey the ruined landscape of Oradour-sur-Glane, and ordinary life on the street during the liberation of Paris. There is nothing grandiose about these pictures, which puts Cartier-Bresson in the much more affecting position of resident, rather than reporter. His portrait of a woman sobbing in the remains of a building, and his misty image of a man found dead at dawn next to a bridge, are both powerful and difficult. The sequence in which a woman at Dessau recognises the person who has denounced her and fights back, is memorably vicious. In all these, Cartier-Bresson was an escaped POW dealing with events around him in the only way he could, as an implicated spectator.

In 1946 he produced a ‘scrapbook’, from which he selected images for the MoMA show: Martine Franck described it as ‘the most precious thing in the world to him’.* Here, there was room to include out-takes, and variations on each frame. His admirers often say he never shot the same thing twice, citing his contact sheets as evidence of his efficient choice of composition. But Cartier-Bresson was at his best when he returned to the same subject again and again, stacking up pictures of a young boy laughing, or portraying Bonnard or Giacometti in their studios as if days had passed while he trained his eye on them. These pictures in particular – portraits of artists and writers that a publisher asked him to take while he was, effectively, in hiding and on the run – are wonderfully quiet, almost conspiratorial. They record the sequential gaze of a storyteller, not the grand vision for a gallery. They suggest, as the album pages and wartime photographs do, that there was most life in him when he was between styles, in danger, and not decisive at all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.