A dream, just before waking. It’s a day or two after Kate Bush’s unexpected announcement of her return to the concert stage for a series of shows later this year. In my dream, Bush takes the form of a child’s tiny hardback book: solid, substantial, not too many pages. On the front cover is a menagerie of cartoon animals, all Smartie-tube colours and toothy smiles. (It looks a bit like the sleeve of Kate’s album Never for Ever, from 1980, but not nearly so borderline sinister.1 In the air, a singing ringing chorus: ‘This Easter egg, full of rain!’ Then Kate, talking as or through the book, says: ‘I want so much to attack them, before they …’ Then I woke up, and her conclusion escaped me.

The only other performers I recall dreaming about are Les Dawson (I was having breakfast with the genial comedian and his wife, as if they were my real, lost parents), and the underground rock group Coil, now sadly no more since the deaths of its two founding members, Geoff Rushton and Peter Christopherson, whom I knew, though not especially well. When I interviewed Rushton (a.k.a. John Balance) in 2000, one of the things that came up was his deep, abiding love for Kate Bush. Actually, it was more like he saw her as some form of household deity or guardian spirit: ‘She’s so hidden … she’s definitely one of the aspects of the Goddess.’

Coil were an out gay, flagrantly druggy, openly occult band, who wove quotes from Aleister Crowley and spells from Austin Osman Spare into their work, forging music of scary abandon and sometimes almost unbearable sadness. They were interested in music as an altered state. You might think no one could be further from England’s chart-music rose, Kate Bush; but peer closer into her work and there are intriguing hints of a sub rosa Bush with Luciferian wings, even (pure speculation on my part) Bush on drugs. If anything sounds like music made in the first disarming glow of Ecstasy, an MDMA honeymoon album, it’s Hounds of Love, from 1985. (That’s MDMA as gateway to a sincere spill-your-secrets relationship rap, rather than a gurning, Duracell bunny rave.)2 Kate’s middle period work is wormholed with leftfield references, quasi-alchemical clues, dark emblems half hidden in the leaping, sparkling songs. (Example: the deeply unsettling, off-kilter ‘Big Stripey Lie’ from her LP The Red Shoes.) Even as recently as 2005, on the more subdued Aerial, such traces remain: the huskily whispered love for mystical geometry in ‘π’,3 the oddly downbeat dream of aetherial flight that is ‘How to Be Invisible’.4

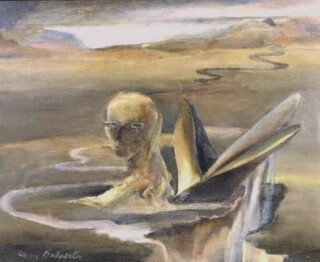

Rushton was very coy about it (as you had to be in those days) but I got the feeling Coil had sampled Bush’s voice and used it, heavily disguised, on their album Astral Disaster (1999). ‘Hidden’, I think, was a good choice of word. There was a long absence between The Red Shoes (1993) and her return in 2005 with Aerial, but the more distant she got, the more public interest and devotion seemed to increase. She was hidden in that she wasn’t one for overdoing things, like publicity, or modishly ‘edgy’ promo images, or explaining her work. And hidden in a way that’s more subtle, difficult to pin down. Her work often recalls (and refers to) a certain lineage of quasi-mystical British art that owes much of its power to never quite spelling things out. My own list would include Powell and Pressburger, Nic Roeg, Paul Nash, Derek Jarman, Anna Kavan, as well as under-celebrated British surrealist painters like Ithell Colquhoun and Emmy Bridgwater. This art revels in the threshold places, the hidden rivers and eerie copses of the British landscape.5 At first it may feel rather chilly, but with time, it provokes an altogether more fearful, feral, intemperate dreaming.

We know all the essential passport application stuff about Bush, and down the years she’s dutifully done the odd unrevealingly bland Q&A, but there’s an immense amount we don’t know. Has she ever taken psychedelic drugs? Has she had therapy? (Reichian, Jungian, marriage?) What music makes her cry? Is she actually a lifelong Rosicrucian? I could make a list fifty items long. Her appeal crosses age, gender, taste; she’s taken on a quite distinct mythic life in our collective dreaming. People who would usually have nothing to do with mainstream rock music (like Rushton) are smitten. She has a huge gay following (queer pagans, radical faeries). Ex-punks and one-time surly troublemakers line up to hymn her praises, when not so long ago she would have been the very model of everything they professed to despise, what with her taste for fuzzy ‘spirituality’ – ley lines, yetis, orgone energy – and tendency towards heavy concept albums. (One side of Aerial has both a Prelude and a Prologue.) Women of all political stripes adore her for the control she has exerted over career and image, for all the easy options she refused; though in fact, she may be the bloke-iest woman in rock. (More of that in a moment.) Rock blokes themselves seem to have an en masse crush on her, though how much this is to do with the real middle-aged mum and canny businesswoman, and how much is down to a long-ago teenager’s tight-leotard dreams, is sometimes hard to judge.

Kate is perceived to be more ‘one of us’ than other pop/rock figures, one of the extended family. There’s a feeling that she’s ‘stayed the same’, that success ‘hasn’t spoiled her’. She’s someone you might have known at sixth-form college, or at your Saturday job (the artier kind, obviously: knick-knack stall at the local market); but definitely a scream down the pub, with her packet of Silk Cut and pint of proper scrumpy. At the same time, people are drawn to her peacock’s-tail otherness, the slightly recherché taste for odd bods like Ouspensky, Gurdjieff and Wilhelm Reich. She has the soul of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, but the robust mien of Mrs Thatcher at a 1980s cabinet meeting. Obviously, no one maintains a position somewhere near the top of the music biz for three and a half decades by being entirely nice and floppy and whichever-way-the-wind-blows. From the off, she was the beneficiary of her parents’ middle-class smarts. A precociously dreamy, sky-eyed teen daughter, she was wisely shepherded. Family and management were merged, became one and the same: Kate Inc., a well-tended cottage industry. Her decision, after 1979’s one exhausting and ill-fated outing, not to tour again, removed yet another plank from the algae-hued drawbridge over the moat. (Consider a few tropes from Aerial: fond dreams of invisibility; pained bafflement at Elvis’s trashy reclusion; the self-imposed exile of Charles Foster Kane; and Joan of Arc, ‘beautiful in her armour …’) Ever since, she has lived a life in many ways more like a writer’s than a modern pop star’s: pop’s own J.K. Rowling. (With her Roman Catholic background and taste for bittersweet mysticism, other names suggest themselves here too: Muriel Spark, Penelope Fitzgerald, Angela Carter, Fay Weldon.) She slowly assumed the status of national treasure, despite or maybe precisely because of the cannily maintained, resonantly low profile. There are forms of politesse and prevarication that can slot very well into a wider tactical scheme. Pragmatic business smarts and keeping the wider world at one remove: why shouldn’t they go hand in hand? Other rock stars may be called out for losing touch with real life; when Bush betrays the same distance it’s thought admirable, soulful, apt. Whatever the soil that sustains this particular English Rose, we obviously consider it healthy.

She gets away with (indeed, gets praised for) things which, presented by other members of the rock aristocracy, would be strafed with scorn. All her albums from The Sensual World to Fifty Words for Snow got far kinder reviews than the patchy material really merited. (I had to consult the track listing of The Sensual World when I realised the quietly awesome title song was literally the only thing I could remember.) It’s hard to dispel a suspicion that were she one more Rock Bloke (a Peter Gabriel, Roger Waters or Brian Pern), critics would be far less kind to her mistakes. Imagine a reclusive Rock Bloke foisting on his impatient public the following: long waits for concept albums full of ‘great mates’ from the 1970s; songs about Bigfoot and snowmen and Stephen Fry reciting daffy gibberish; unadventurous marking-time remixes of old material. Someone, in sum, who displayed every symptom of having let zero new music into his manor house for twenty or thirty years. I’m not convinced our huffy Rock Bloke would get the same across-the-board critical hosannas as Bush. There’s a song on Aerial about her son Bertie: ‘Lovely lovely lovely lovely Bertie! The most wilful, the most beautiful, the most truly fantastic smile I’ve ever seen!’6 Would Sting, say, be as gently indulged, should he trill something similar? Granted, we may look more kindly on a mother’s paean to her first child; but there is a line between a song about maternal psychology and just plain yuck, and Bush comes perilously close to country dancing all over it. (The song is smarter than it might at first seem, and involves balancing her shameless gush against a rigid classical line – an interesting idea that suggests both selfless love and disciplined nurture. But in the end that’s what it remains: an interesting idea.)

Family is important to her; not just in the way it is to most people, but as a protective screen that has kept her relatively compos mentis in an insanely topsy-turvy, id stroking industry. Her first long-term partner, bassist Del Palmer, still works with her in the studio, as does her husband, guitarist Dan McIntosh, alongside her two brothers Paddy and John. Consult the small print of Hounds of Love and you’ll find that even the slightly risqué photos of Bush were taken by brother John. And on Aerial and Snow her son Bertie emerges as both subject and vocalist. She’s fanned a duplicate family out around herself in art as in life. Which seems like an eminently sane thing to do; even if a small, quiet voice in my head wonders if it’s maybe not too nice and comfy and convenient. The very thing that has presumably sustained her, kept her sane, may also be the thing that’s softened her edges. Being always surrounded by family and mates in the studio may be a great recipe for solid longevity, but you do sometimes wonder what might result from a collision with a more wilful, uninvested, unpredictable producer who could prise her out of her comfort zone. (Controversial opinion: the best Kate Bush track of recent years is in fact ‘When I Grow Up’ by Fever Ray.)

I used to dream of a Bush-Coil hook-up: Bush reflected in a darker mirror; mercurial, androgynous, on fire. It wasn’t actually that much of a stretch: if you compare middle-period works such as her Hounds of Love and their Love’s Secret Domain, the sonic palette isn’t so dissimilar.7 There are the strange chthonic voices on Bush’s ‘Waking the Witch’. Her quoting of ‘It’s in the trees, it’s coming!’ from Night of the Demon, a film all about a Crowley-esque mage, recalls the sampled voice (Charles Laughton reading from Night of the Hunter) on Coil’s own ‘Who’ll Tell’. The edge of the labyrinth. Demons on the living-room carpet. Innocence come to grief.

If you go back to Hounds of Love, the first thing you notice is that in those days she took far more risks with her voice: there was far more higher register and far more lower register, far more affectation (in a good way), far more play. It often sounds like she is obeying the pulse of a very personal ceremony, with its time signatures and textures all over the place. These days she relies more on default settings: there are too many songs with just Kate and her rainy-day piano. ‘We become panoramic,’ she sings, but the music never does, quite; it’s mostly ‘qualidy rock’ that’s a smidge too smooth, predictable, homogeneous. All her guest artistes are men of a certain age, from either Saturdays-gone-by light entertainment telly, or 1970s rock. If you can gauge someone’s taste for artistic risk by consulting their visitor’s book, then – well, let’s take a look: Lenny Henry, Rolf Harris, Dave Gilmour, Nigel Kennedy, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Lol Creme, Gary Brooker, Andy Fairweather Low … I can’t be the only Kate fan who puts their fingers in their ears when Rolf Harris and Stephen Fry come in as guest vocalists.

‘Hounds of Love’, though, is quite simply one of the most beautiful songs pop music has ever produced. It’s not just a song about abandon, but one that embodies feelings of anxiety and abandon, smallness and bigness, in its dizzying drive and texture and in Bush’s joyously unhinged singing. Her keening vocals suggest adult poise on the verge of helpless childhood fall. The whole song, but especially the line ‘his little heart, it beats so fast,’ still automatically reduces me to tears. The arc she makes of ‘hold’ in the yelp of ‘hold me down’ is truly overwhelming: at once pained and lost and powerfully erotic. Listen to the closing minutes of ‘Running Up That Hill’, with its muted chorus of multi-tracked Kates: screaming, grieving, witchy, shattered, a sonic foam rising above the song’s jagged tribunal.8 It’s a very odd song indeed. At the very least, it claws and rubs at the dissolute line between ecstasy and abjection in a way that was, shall we say, uncommon in mainstream 1980s pop: ‘Tearing you asunder … do you want to know it doesn’t hurt me?’ Or listen to the way she enunciates the line ‘you never understood me’ in ‘The Big Sky’, her voice somewhere between a caress and a storm warning. Listen to the bizarre chorus she makes of her voice, how it conveys utter exhilaration at its own just glimpsed possibilities. Such wayward joys begin to explain why some of us were so entranced by her to begin with. (I clearly remember hearing ‘Running up That Hill’ for the first time, on the radio in 1985, on what happened to be my birthday. I immediately rang several people to tell – or maybe warn – them about it.)

We don’t necessarily expect artists to keep taking such giant leaps throughout a long career; but the wild glee and panic play seem to have all but evaporated lately. At the end of a long, gently rocky sequence on side two of Aerial there’s a brief, silvery glint of multi-tracked Kates, but they’re promptly flattened by some awful, hackneyed ‘rock out’ guitar. Then right upon Aerial’s crest and end, she unexpectedly bursts into joyful, pealing, baffled laughter, apparently away with the birds and their morning song. ‘What kind of language is this!?’ It’s one of the only times in late-period Kate with the same gawky, light-headed charm and strangeness of the early days. A small thing, easy to overlook, but on the tiny sticker attached to the CD of Aerial it’s referred to as ‘the new double album’ – as if we were still in the gatefold 1970s, not the digital download 2000s. The Bush home studio, far from being a safe place for risky play, seems to have become a playhouse for her roster of greying rock chums and light entertainment panjandrums. All deeply nice blokes and everything, I’m sure, but maybe a certain fluffy-slipper retreat behind ‘nice blokeness’ is one of the problems here.

There’s an odd thing about both Aerial and Snow, though: under that chummy, soft rock exterior a lot of her new songs sound mournful, even desolate – full of characters middle-aged or older looking back with wistful disappointment and regret at what might have been. They’re figures who can’t come together or stay together or who just missed staying together: adrift, vainly searched for, trapped between or beyond worlds. There’s a sense of lost or frozen time: of double-sided or divided people, who at some point let their more reasonable selves take control, and lost inestimable treasure through the deal. ‘A sense of nostalgia for what never was,’ as Pessoa put it, ‘the desire for what could have been; regret over not being someone else.’ And, just maybe, the ambiguous cue for her own return to the spotlight.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.