There was a lot of racial tension around bebop. Black men were going with fine, rich white bitches. They were all over these niggers out in public and the niggers were clean as a motherfucker and talking all kind of hip shit.

Trane liked to ask all these motherfucking questions back then about what he should or shouldn’t play. Man, fuck that shit –

Bird had this white bitch in the back of the taxi with us. He’d done already shot up a lot of heroin and now –

There is a long and slightly disreputable tradition in jazz of oral biography. The ‘as told to’ voice here belongs to Miles Davis, in Miles: The Autobiography, first published in 1989 and officially attributed to ‘Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe’ (see also Lady Sings the Blues by ‘Billie Holiday with William Duffy’). Depending on mood, ethnicity, ideology, drug of choice, an oral biography can strike the reader as an authentic reproduction of voice, in all its self-contradictory rhythm and curl – or borderline racist, like some Victorian anthropologist’s respectably freaky show and tell.

A couple of things should be made clear: one, Quincy Troupe is a black poet and academic, not some ofay hack-cum-hustler; two, Miles: The Autobiography was released at a time when Davis was looking to get a little payback on his place in the tradition. He had those storm-warning eyes of his on the emerging rap/R&B/CD-reissue marketplace, and his bad-mouth persona didn’t hurt the book’s profile. Davis grew up in a stable middle-class home: his father was a hard-working dentist, a cultured and well-read man active in local politics; Miles attended Juilliard with a generous weekly allowance from Pops (enough, indeed, to help support an indigent Charlie Parker), and later hung out with writers and artists in postwar Paris. Consequently, some readers of Miles: The Autobiography found the mooted authenticity of a voice that felt like a brass-neck steal from Donald Goines’s Dopefiend or Iceberg Slim’s Trick Baby to be, at best, a balefully corny performance. On a deeper level, though, that voice hints at all sorts of unresolved tensions and uncomfortable truths about jazz and its place in postwar American life. How America sees – and hears – itself. How it imagines (or expects, demands) certain people sound. What truths it assigns to particular groups, while denying access to others.

Such tensions were manifest in jazz from the off, and reached a thorny apotheosis with the mid-century advent of the style known as bebop. (Bebop reset the spine of popular standards, vaulting off into a far more rarefied harmonic atmosphere.) Jazz may have been born and raised in brothels, gin joints, chthonic nightclubs, rather than respectable performance spaces, but it was a music of devilish complexity, exacting technical fibre. Musicians in touring jazz bands and orchestras had to satisfy the clamour of their weekend audience for beats that could be danced into the floor; satisfy their own high creative standards; and also find a way to leap unscathed between dense volleys of beckoning myth and image. In Charlie Parker’s 1940s heyday jazz was one of the few spaces where black performers might carve out a life of relative artistic freedom, mostly on their own terms. How do you convey all the snares and banquets, peaks and deadfalls, of a difficult but intermittently joyous life like Parker’s? You get on stage and blow, and shape something so expressive, so technically ferocious, so emotionally acute, it obviates any need for oh-by-the-way footnotes. Accept it, or don’t: as existential fact it remains inviolable, undeniable. Unearthly sonic signatures woven from everyday air; flurries of notes like Rimbaud’s million golden birds set free: no one else could do this one thing he did, exactly the way he did it.

Charlie Parker was one of the first deepwater jazz players to seize the public imagination. It may have taken a fateful early death in 1955 to settle his portion of true infamy, but mythic status was then assured. A plump, sharp-taloned Icarus in after-hours mufti, he was already the subject of a votive cult among bebop obsessives. Soon after his blurry end, aged 34, a fond graffito rose and sprouted all over New York: Bird Lives! Parker’s sad extinction released myriad afterlives: musical colossus, modernist exemplar, contested emblem of racial politics, finally even the recipient of the paste crown of a posthumous Hollywood biopic. Parker’s flinty, recondite music slowly shades into the background; he becomes better known for a ruinous pile-it-high lifestyle, for being the only addict pre-Fassbinder to get fatter, not thinner, as his habit deepens; for plunging into late decrepitude only to die in the lap of luxury, in a high-society eyrie belonging to the Rothschild child and ‘Jazz Baroness’, Pannonica de Koenigswarter.*

True believers want to reclaim Parker from a now (as they see it) deeply degraded image, emphasising instead the dare and complexity of his music; this is already a gamble when many fair-weather fans tend to shut down at the first mention of flattened fifths and roving thirteenths. Even if you’ve loved this music for half a lifetime, you can find the algebraic lingo of jazz theory about as clarifying as a book of logarithms baked in mud. Biographers first have to explain the tradition Parker emerged from – solo improvisation within a many-handed ensemble music – but also show Parker’s own itchy, wasp-sting style as the fruit of one vulnerable life, no other. A life that was severely circumscribed, and correspondingly over intense. Stamen-soft pollen-dry old side-men, quoted in these biographies, testify that from early on the boy Parker was manifestly different: one of those characters who enter a room and social space instantly shapes itself around their fizzing tempo. Even contemporaries who never liked Parker don’t try to deny it: he lit the workaday world on fire, left you wrung out and twitching. He took charge, ran rings, pulled the carpet out from under – both on and offstage. If you’re going to flag the uncommon flair of Parker’s playing via talk of chromatic scales and variant chords, you’d best find a way of doing so that doesn’t wash the polydipsic chaos of the man out of the picture entirely. Parker’s song was resolutely unsentimental, a sometimes harsh, hurtling thing: he put all his seducer’s wiles into his life, not his music. So why does this spiky, astringent music touch so many of us, still?

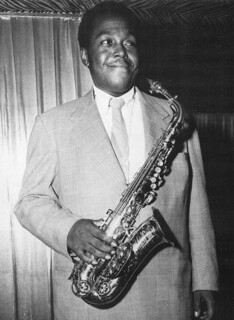

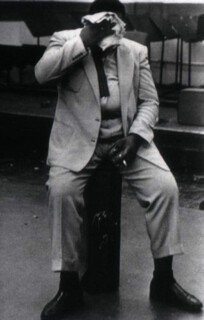

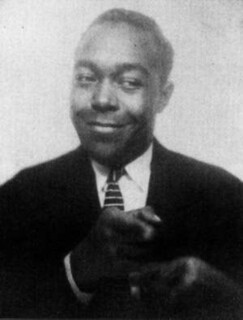

In almost all the surviving photos of Parker, he sports what you would have to call a characteristic grin. Clean or stoned, upright or unsteady, in transit or out of reach, there it is again: a natural bodhisattva’s airy acceptance of whatever’s next. The full catastrophe! He seems to mingle contrary humours of unconcern and cupidity in one wobbly cartoon smile. Here’s a snap from 1948 (below): Parker as pinstriped Michelin Man, behind who knows what speedball of bottles and tines, being euphemistically ‘escorted’ out of a club by prim drummer Max Roach and adoring disciple Dean Benedetti; a terminally dishevelled Bird, but the grin is intact, if anything even wider than usual – it looks alarmingly like victory.

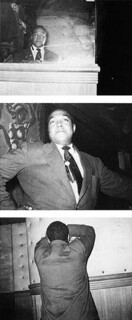

William Burroughs said that you should never trust anyone who looked the same from photo to photo; Parker can appear a wholly different person across a single roll of film. In one snap he is spruce and trim, alight with boyish glee, like he just found a toy alto in his Xmas stocking; a few weeks later he’s a slumped old man, bursting at the seams, a zoot-suit sofa set out on the kerb to disintegrate in the rain. Spend any time reviewing such images and you come to an unexpected conclusion: our supposed King of Cool is, if anything, notably un-‘iconic’. In a bandstand snap from 1948 it’s bassist Tommy Potter and a razor-cheeked young Miles who look like the hippest cadavers in town. In another band snap, from 1952, the likes of Oscar Peterson and Ben Webster are prince-like, sunny, resplendent; Parker looks thirty years older than his 31 years, an ailing rhino in a crumpled suit. There is a shocking paparazzo pic from 1954 of Parker exiting a police van, entering Bellevue public hospital: filthy suit, shirt awry, trousers ridden up to his mottled knees. In Celebrating Bird, Gary Giddins includes three photos I’d never seen before, taken just before Parker’s death. (Frustratingly, Giddins supplies no background context.) In one, Parker turns his back to the camera and covers his eyes, as if caught in a game of hide-and-seek. (Who with? Behind what shadows and posts?) In another, we see his reflection in a smeary nightclub mirror. In all, he appears spaced-out, placid, playful, gesturing from inside some deeply inaccessible personal beatitude. He looks like a happy ghost.

In my teens, I made my own portrait of Parker. It must have been circa 1975: a small town in Norfolk, a lacklustre grammar school, art A level. Parker’s insanely cool milieu seemed a world as distant as the British Raj, or cowboys on the range. All my bebop reveries played in scratchy, staccato black and white. The Bird of my painting bursts into colour, if not life – he has the dubious solidity of a cheap garden-centre Buddha. The overworked surface is jagged to touch: piled-up arrowheads of paint, all blinding whites and golds, around the stony brown island of his face. I somehow caught something of the eyes: a flicker of American Indian ancestry, a musician’s selfless self-absorption, a bit of junkie sag. But for all its mimed frenzy, the picture’s a bit flat. The subject fills every last inch of pictorial space: no breathing space, nothing but Bird right to the edge of the frame. I was too young to work any kind of angle on the man’s psychological fire or frailty. He feels way too close, yet still completely unreadable. Then again, there’s part of me today thinks this isn’t such a bad interpretation of the way things were with Bird.

At the time, I owned just the one Parker recording: Charlie Parker on Dial: Volume 1. The sleeve shot is a study in grey, Parker looming like an Easter Island god. The sleeve notes, by the Bird fanatic and Dial label founder Ross Russell (he later wrote the first Parker biography, published in 1973), detail a period on the West Coast in 1946 which produced agonies in Parker’s life and a series of lustrous recordings. I still remember the several oily scenes Russell conjures up. Parker suffering acute heroin withdrawal in an airless LA garage: a metal cot, no heating, his thin spring coat the only scrap of warmth. He eats nothing for days on end, drowns himself in cheap booze. Later, he is found dazed and naked (bar socks and cigar) in a hotel lobby at midnight, and led back to his room three times. The long night finally ends when he nods off, the cigar sets his cheap mattress on fire, and the hotel has to be evacuated. In 1975, I read and reread this litany of stains and wounds and had my head turned around by the music and somehow it all seemed of a piece. None of it struck me as especially odd or extravagant or depressing.

Parker fell into the world in late summer 1920, on one side of the confluence of two muddy rivers. He was born in Kansas City (Kansas), before the family crossed the bridge to Kansas City (Missouri), which turned out to be provident ground for a future jazz-man. At the time, Kansas City was – in the parlance – ‘wide open’: there was an unofficial alliance between a corrupt police force and the wily, indefatigable crime boss Tom Pendergast. Giddins: ‘Entertainment also flourished. The clubs and dance halls operated day and night, and the best musicians in the country were attracted as much by the competitive atmosphere … as by the possibilities of employment.’ There was no such thing as ‘after hours’: no time, day or night, when beady young comers couldn’t find somewhere to hang out, catch musical giants at play, exchange lore, pick up soul-ageing work.

Parker was named for his father, Charles Parker Senior, a singer/dancer in the tough world of black vaudeville until an over-fondness for strong liquor precipitated a slow staggered decline. This seems to have been a man who drifted into (and out of) things: towns, marriages, jobs. He ended up working as a chef on a Pullman train. As with accounts of Billie Holiday’s childhood, the father fades in and out of focus, an oddly discarnate presence. Charles Senior may have been an unfortunate role model for his son: itinerant entertainer, suddenly (and vexingly) present or suddenly (and mysteriously) absent. In most accounts, it’s Parker’s steely Baptist mother who dominates: if Charles Jr had a better than average childhood, it was down to Addie Parker, who toiled hard and made his future the focus of her life. None of the books pries very far under this bright but somewhat inert picture. The near suffocating attention Addie lavished on Charlie feels not entirely healthy: maybe not the full Oedipal, but definitely on the doorstep. Routes around limited space, humid closeness, proxy mates: one exiled Charles and his over-adored replacement. When Charlie brings his young wife, Rebecca, onto the scene, she and Mama Parker merge into one edgeless figure, set up to tend his majesty’s regally unpredictable needs 24/7. (It’s perhaps no surprise he grew into a man with such little impulse control.) At one point in Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker, Stanley Crouch describes Mrs Parker’s attitude to Rebecca as that towards an ‘interloper’; otherwise, no one embellishes this score with any oblique psychoanalytic riffs. (Oh, for a quick burst of Melanie Klein!) There’s a muggy feeling of various unexamined ellipses, lacunae. The most obvious tranquillised elephant in the room: if things were so cosy, how to explain Charlie’s greedy embrace of pain-killing drugs at just this point? A few weak shots of morphine administered after a car crash are nominated the fatal glass of beer; Chuck Haddix, in Bird, then has a visiting GP suddenly burst into dark warnings about the hell-broth of addiction. This seems a tad unlikely. (According to Haddix, the doc warns that as an addict Charlie will have – at best – twenty years left. Twenty years! To a young black man in that time and place, two decades of intermittent bliss hardly counts as the sternest counsel imaginable.) If Haddix seems lost in some creaky 1930s melodrama about the evils of narcomania, Crouch has a whole palette of gory details regarding sexual organs, soiled bandages, abortion and afterbirth, which sits very oddly indeed with his general professorial demeanour. It’s as if both writers had caught Birditis by osmosis: everything feels simultaneously too close, but strangely unreal. Nothing quite coheres. (Also: why towards the end of his life did Parker become quite so obsessed with not being buried in his and his beloved Mama’s hometown?)

Charles Jr had a typical spoiled child’s approach to new enthusiasms: taking them up and putting them down, not ready for the slow circular grind of daily practice. Two years passed without any signs of extraordinary musical aptitude; as Giddins has it, only young Charlie’s ‘obsessiveness begged notice’. Then the sonic gyroscope seems to shift inside: he digs in, locates somewhere to play from, aim towards. Finally settled on the alto sax, Parker put in the required slog. The same pattern on the bandstand or off, learning his instrument or injecting drugs: long idle hours of dust and scratch and empty mind; and then this sudden click of magic acceleration, curling overflow. Gnarly young apprentice Charlie slowly takes on the shiny lineaments of mythical Bird. (The nickname was a combined tribute to Parker’s outsized appetite and his far-sightedness. A literal on-the-road incident: speeding to a country gig, the car Parker was in ran over some farmer’s ‘yardbird’. Everyone else in the car saw dead poultry; Parker, always one thought ahead, saw that night’s chicken in the pot.)

Initially, Parker would have played for an almost exclusively black audience: for other musicians, at so-called ‘cutting contests’ and long after-hours jams; or for Friday and Saturday night crowds who appreciated flair and artistry but most of all came for the big weekend get-down catharsis. Crouch gives the best account here of the jazz bands of the 1940s: how they played together, changed the air in the room, rose up as one through dancing bodies. This was the soil Parker thrived in: any ode to his improvising genius has to acknowledge the galvanising friction of all those he played with and learned from. Many contemporaries revered the young upstart for his bandstand technique, but resented him personally: the jive and murk of his life brought jazz back down again to the myth of an elementally untidy black life, the same old tale of two sides of the river and the bad side of town, the need to explain things all over again from scratch when it was way past time to have to crank out such tired footnotes – jazz isn’t a silly gimmick, we are artists, we are professionals. Parker – the king of id – refused to acknowledge any real boundary between private impulse and public decorum; his discomfiting and unpredictable behaviour even got him banned from Birdland, the New York club ostensibly named in his honour.

You maybe catch a faint echo of that exasperated tone from Parker’s biographers, too, as they try to explain just why jazz was once such a huge, and hugely catalysing, part of public discourse in America. Haddix makes bafflingly large claims for his own work (‘Separating the man from the myth has proved to be an elusive effort for those who have written about Charlie – until now’), but has no real surprises or new slants in store; his is a sturdy, unexceptionable, journeyman study. Celebrating Bird is a revised edition of a book that originally came out in 1987, and is the one I’d recommend for curious outsiders. Giddins does the best job of explaining Parker on a technical level, what it was he did to earn his reputation as a peerless innovator: the tensile ‘logic and coherence’ behind what might seem to outsiders like ‘an explosion of sound, a scramble, an incomprehensible provocation’. How he worked a breathing space deep inside old riffs and drowsy songs, prising apart tired chord arrangements and fanning them out round the waiting night in kaleidoscopic new variations. Parker’s tone on the alto sax was clipped, light, skittering – actually more like solo piano than other saxophone players of the time. (You can definitely hear the hours he spent listening to the blind keyboard maestro Art Tatum. Can we also hear echoes of his father’s tap dance and later clickety-clack train-bound times? It seems an obvious thought but no one raises it.)

Even during his lifetime, jazz fans were obsessed with Parker in a way they simply weren’t with other, equally gifted players. On-the-hoof Boswells trailed Parker from club to club with clunky reel-to-reel equipment, back when it was like carrying a circus clown’s car on one shoulder of your baggy suit. Giddins makes a stab at totting up the figures: ‘More than 350 Parker improvisations recorded privately between 1947 and 1954, excluding posthumously discovered studio performances, surfaced in the thirty years after his death.’ But he’s already erased that figure by the bottom of the page. In a revised footnote he reckons the initial estimate conservative: uber-fan Dean Benedetti alone, in the year 1947-48, collected more than seven hours of Parker solos and snippets. Monomania like this can be hard for outsiders to process. Isn’t this obsession with technique alone a bit lopsided, a bit inhuman? What about emotional sway? I’d have liked one of these true believers to argue Parker’s case more, rather than take it as given that his was an irresistible magic. I love Parker’s music, but it’s not what I’d choose to smooth anyone into jazz appreciation. It can seem hard-shelled, intransigent. (The two words of true-believer praise that crop up most are ‘virtuosity’ and ‘velocity’.) If you did have to play devil’s advocate, the brief might go: for all his technical verve and power, Parker’s is a limited palette; his playing, while breathtaking, rarely admits softer moods or qualities – anything of drift, reflection, loss. The one time he instigated a more calmly interpretative project – 1950’s Bird with Strings – it was not an unqualified success. Parker’s impatient stiletto tone guts the delicate membrane of his chosen mainstream standards; it doesn’t sound as if he is interpreting these popular songs so much as assailing them, giving them a hard time to see if they pass muster.

It may not be coincidental that the one performance many people cite as Parker’s most moving is one he himself disowned. I was stunned when I first heard ‘Lover Man’ on Volume 1 of the Dial collection† – this really is art that leaves you nowhere to hide. You might say it’s the one time his life and art roughly coincided – where you can read one through the other. A recording session had been booked, but Parker was out of heroin, and drinking heavily to numb the pain. A healthy (i.e. heroin-soaked) Parker might have breezed through ‘Lover Man’, playing abstruse games with all the harmonic underpinnings, half-mocking its sentimentality, exposing all the song’s rubbery bones. Instead, he’s audibly out of sorts: you can hear how much it costs him to summon the breath to make it through to the end. This is an unbuttoned rendition you either find unbearably moving (while noting that this close to collapse Parker’s sense of artistry still kicks in); or you think, as Parker did, that it should never have been made public. (He was reportedly furious with Russell for releasing it.) I don’t think our only response to ‘Lover Man’ has to be a meanly voyeuristic one. It may be a cracked whisper rather than his usual keening flight, it may have come from a pitiful, blasted place, but it sounds like a last desperate attempt at communication, before the lights go out.

One of the problems with trying to profile Parker may be that everything is already upfront, undisguised, heaped up in a monstrously untidy pile. Parker wasn’t one to tiptoe through the realm of the senses; there was very little interfering static between his having a lurid idea and making it happen. Any biographer used to sieving through decorous public behaviour for dark and hidden motifs might well exclaim (as someone once did of Max Beerbohm): ‘For God’s sake, take off your face and reveal the mask underneath.’ It leaves the biographer with the unfamiliar project of clothing their subject, not stripping them bare. Which is not necessarily a bad thing with a life like Parker’s, which can feel over-itemised: it might force the writer to come up with deeper, odder, more illuminating personal responses.

In 1981, Stanley Crouch started interviewing people who’d known and played with Parker; 32 years (and a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant) later, Kansas City Lightning represents the fruit of all his obsessive research. Well, kind of, as it turns out that this is only the first half of Crouch’s long-anticipated study: by the end of its 334 pages Parker has just turned 21, and all the most celebrated music and more infamous Life of Bird stuff is still to come. Crouch builds up a steady, rising momentum and then – dead air. Halfway through the premiere of some brazen new polyphonic suite, the band leader brings his hands down, draws a halt and marches offstage. Crouch has always been a contrarian, but his decision to break off the story this way seems notably odd – especially as you’d think Parker’s curt, fiery life had a pretty singular integral arc. (Who knows what psychological horse-trading, and/or grim publishing politics were involved in this decision, but it now looks like Crouch will spend more time on this biography than Parker himself spent on earth.) Also, some kind of drag kicked in for me about two-thirds of the way through: I hit a wall and had real trouble getting back into Crouch’s expansive, carbo-bulked step. In smaller portions, Crouch dazzles; as a whole night’s mezze, the text feels just a bit too rich, dense, self-delightedly overcooked. It confirms a prior feeling that Crouch is at his best in the short-jab arena of essay, polemic, reply.

When Clint Eastwood’s 1988 biopic Bird came out, Crouch wrote a piece (‘Birdland: Clint Eastwood, Charlie Parker and America’) which wasn’t just critical of this or that detail: it felt more like an attempt to unmake the film, to deny Eastwood (or any white person) the right to make such a film. (I thought the essay fundamentally wrongheaded, but as rhetoric it was unputdownable; his 2006 collection, Considering Genius, containing essay-length appreciations of Miles, Mingus, Ellington et al, is essential reading.) Many people in jazz see Crouch as a kind of rebop Christopher Hitchens – an ex-Free Jazz maven who blimped out and has become more and more inflexibly conservative with time. Big Poppa with the rod of correction, dismissing whole swathes of new work, cleaving instead to dependable figures like the trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. (I’m not enough of a buff to judge someone like Marsalis in Crouchian terms – he has a deeply felt and interiorised sense of the music’s history, theory and technique – but on instinct alone I’m baffled: even at his best Marsalis seems like an exemplary but perfectly lifeless simulacrum or museum piece.) Crouch wants to explain where Parker came from in order to reclaim where jazz subsequently went: a way to underline his own – some would say perilously nostalgic – vision of what jazz always was, and should always remain. Through Parker he can celebrate the majesty and integrity of certain black cultural traditions – most of all, the ESP itch and summons of big band improvisation-within-bounds. And it has to be said, the first half of Kansas City Lightning is a flat-out joy and revelation: in the sections that deal with bandleaders, Saturday nights out, food, clothes, seduction, argument, Crouch’s prose catches fire. He’s winningly suasive on the whys and wherefores of the era; the only problem may be that he is far more memorable on the ‘times’ of this great prewar moment than he is on Parker’s own singular ‘rise’. You look around for Bird, and he’s gone. You can just detect a small splash of exit at the far edge of Crouch’s frame.

In December 1945, Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and others took a train west for a big club date. Stopped in Chicago overnight, they took the chance to jam with some local musicians and missed their morning connection on the sleek Santa Fe Chief; they ended up on a far slower mail train, stretching the two-day trip out to nearly a week. Idling at a tiny depot in the middle of the Nevada desert, Dizzy looked out the window only to see Bird staggering off on foot across the endless empty plains, his battered saxophone case under his arm. He was sick, and trying to score.

Haddix gives a nice account of this tale (originally related by Ross Russell), and it’s one of the few times here you get any sense of air, space, American horizons, a world beyond the shades-drawn jazz life. Time measured out in spoons and bottle-tops, in stale boarding-house bedrooms and tiny clubs, in street corner telephone kiosks. In Bird Lives! Russell has Parker conducting half his life in taxi cabs: he hid out in their back seats to swallow pills, write music, consummate relationships, sleep; held on to them for entire days, as combination office, waiting room and bedroom. Even at rest, Parker keeps moving. He would nod out on the bandstand then snap to, pulling ferociously inventive lines up from the seabed of near coma. In the long run, such all-or-nothing logic exacts a heavy toll: physical enervation first, but one’s emotional/intellectual life can also take a protracted beating. It’s hardly conducive to any kind of art that might grow and deepen over a lifetime. You develop certain muscles at the expense of others. You don’t work out how to pace yourself. You do not, in Ishmael Reed’s radiant words, learn how to fall. You become rooted, boxed in, inflexible. Even when Parker went abroad, he didn’t soak up any new influences. Miles went to France and learned to speak existentialist, fell hard for Juliette Greco, was awakened to African textures, checked out Picasso. Bird went to France and cottoned on to a Belgian bebop fanatic and (uh oh) pharmacist, who liked to befriend the premier league of US jazz addicts. He had a whole room full of pure legal narcotics: a dark rainbow of graded heroin from Marseille, Naples, Beirut, Seoul, Istanbul, pure pharmaceutical morphine from Basel. For two weeks, Bird had the strung-out time of his life, curled up inside this nest of thorns.

In truth, it’s hard to see where Parker might have landed next, if he hadn’t exited when he did; there’s a melancholy feeling of peaks already scaled, with only decline or repetition ahead. He was well on the way to being the jazz equivalent of a punchy old boxer, someone the up-and-comers use to train with, before moving on. Deprived of heroin, all Bird’s Grimm-paw prickliness could return with shocking force. In 1955, following an especially sad, disordered set with Parker and the equally troubled Bud Powell, the young bass magus Charles Mingus dragged up to the microphone and apologised to the audience. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, please don’t associate me with any of this. This is not jazz. These are sick people.’

There came a point when Birdland closed its doors, 52nd Street emptied. (There were political manoeuvrings behind the hey-daddyo jive: worries about returning servicemen having way too good a time in those sorts of club.) In the jazz world, things were changing too. Broad-cloth bebop suits already seemed a bit clownish. Some players still drew on bop’s harsh, stuttering example, but many more didn’t. Some lit out for a slower, more reflective path, a music of languid West Coast breeze: limpid, crystalline, Pacific blue. Miles was looking inward, and also networking: his sharp clothes, measured contempt, subtle fire, appealed to a younger, hipper crowd. None of these developments could have been plotted from Bird’s example, and none suited his particular sensibility. He was 34. There are heights of success which feel like a very personal form of failure.

Ross Russell still gives the best – the most distressing – picture of Bird’s final weeks and months. ‘His movements were mechanical, erratic, purposeless. They followed a mindless pattern of disorder and whim. High life had become low life.’ He spent whole nights riding the subway alone. He talked incessantly about death, leaping into the river. He was sick now, deep down in his peculiar sense of time; the old sure feel for currents and vectors, exits and hideaways, had fallen away. He was out of time. He zigzags through rainy New York, drinking port wine behind the dead windows of abandoned buildings: a nest fashioned from ulcers, debt, old reeds, blood. He’s never felt such a bitter taste in his mouth before. A rough bird, jet black, alights on his hand. He recalls an old golden song, from long ago. ‘Goin’ to Kansas City, sorry that I can’t take you.’

There is one way of looking at Parker that none of these books touches, which is that the arc of his success also measured the extent of his failure and fall: he went too far, too fast, in one solitary direction, leaving himself no outs, alternatives, breathing space. (Yves Bonnefoy: ‘Love perfection because it is the threshold/But deny it once known, once dead forget it/Imperfection is the summit.’) Maybe the reason we’re still drawn to Parker’s oblique, messy outline is that he wasn’t any kind of seamless paragon: it was never brilliant technique that was the lure, but the imperfect, unreadable man. For all their careful, respectful merits, a few weeks after finishing these books I could barely call up a single memorable detail, whereas I can still bring to mind whole sections of Russell’s much disparaged Life of Bird. (Not for nothing, but once you get past the pimp-face stare-down, Miles’s autobiography is also effortlessly illuminating on Parker’s personal toughness and nonpareil musical technique. He gives us a Bird who’s a painter in sound, a Picasso of syncopation: a beady-eared Cubist playing four versions of a tune at once.) Russell’s account – dodgy though some of its anecdotal evidence may be – feels like it was written in a rush of genuine excitement. It’s not pretty, but Parker is a genuine presence in the room: sweaty, sulky, delicate; brutal, playful, paradoxical. Half-flesh, half-feather: carnal daemon, weightless changeling.

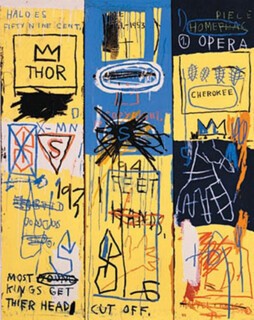

I keep returning to all the different images: sometimes I think we might discern more of the true story here, if we blur our eyes and dream a little. All the photos, but also certain uncanny paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Beauford Delaney. Like this lovely photo from 1940: avid young Charles, barely twenty, with a great big springtime smile on his face, pointing to someone or something just out of frame: a bebop presidential candidate, working the hustings. The first few times I glanced at it, I didn’t really see: it’s actually Bird having fun inside a Kansas City photo booth, and the someone or something he’s pointing at with such unabashed glee is himself. He’s finally found someone he can’t fleece or best or seduce – and, it appears, it’s only made him all the happier.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.