There was a time within living memory when a survey of Klee’s painting like the one at Tate Modern – 17 rooms, 130 works – would have been the event of the season (it’s on until 9 March). I remember even scoffing a little in the 1960s at London’s appetite for shows of the ‘tragic comedian’, antidote to Picasso’s vehemence or Matisse’s fundamental coldness. For good or ill, that moment is past. The galleries at Tate are mostly not crowded, and I had the impression that the respectful visitors, bending over the ropes to get a better look at the artist’s small things, found it hard, ultimately, to understand his cast of mind. ‘Klee is like somebody out of an E.T.A. Hoffmann story about the small-town Germany of the 18th century: comfortable, musical, modest and fantastic,’ Clement Greenberg once wrote. Or later in the same essay:

Klee is not subversive. He is well content to live in a society and culture that he has robbed of all earnestness; in fact, he likes them all the better for that. They become safer, more gemütlich. Far from being a protest against the world as it is, his art is an attempt to make himself more comfortable in it; first he rejects it, then, when it has been rendered harmless by negation, he takes it fondly back. For notice that Klee’s irony is never bitter.

Rendering the world ‘harmless by negation’ is not what we have been led to expect art, especially modern art, to do. And ‘taking it fondly back’ sounds genial to the point of smugness. Matisse is allowed to say, famously, that his art was intended as ‘a comfortable armchair for the tired businessman’. But that is because his art so often invites us not to believe him.

Klee’s whole attitude to art-making is elusive. Occasionally the poems he jotted down in his diary seem to help. There is one written in 1914, probably soon after war had been declared, which begins:

The big animals: despondent

at table: unsated.But the small cunning flies

scrambling up slopes of bread

inherit Buttertown.

This seems like the script for a Klee picture, and the mood is almost optimistic; but the poem ends four verses later on a different note. The translation is Anselm Hollo’s:

The moon

in the railway station: one of the many

lights in the forest; a drop

in the mountain’s beard:

that it doesn’t trickle!

that it is not pierced by the cactus thorn!

that you

do not sneeze, and

burst

this bladder!

The little pictures in the Tate exhibition often seem to be turning towards us – towards the ‘you’ in the poem – and asking us not to sneeze, not to disturb the Klee moonlight. But the year of the poem is not auspicious, and the poem as a whole, although it does not have any other tactic – any other diction – to put in place of the small flies’ cunning, seems aware of what smallness and cleverness are up against in the early 20th century. ‘Man-Animal:/Clock of Blood’, reads the two-line stanza preceding the last one. Klee’s paintings almost always have some such ominousness in the background.

There was, we know, far worse to come. On 1 February 1933, two days after the swearing-in of Hitler’s coalition government, the Nazi paper Die Rote Erde carried a full-page article under the headline ‘Art Swamp in Western Germany’. The target was Jewish domination over the Düsseldorf Academy, which had been clinched, so the writer believed, by Klee’s appointment as professor two years before:

And then the great Klee makes his entrance, already famous as a teacher of the Bauhaus at Dessau. He tells everyone that he has pure Arabic blood [apparently Klee had let slip that his mother’s family may have come originally from North Africa], but is a typical Galician Jew. He paints ever more madly, he bluffs and bewilders [er blufft und verblüfft], his students are gaping with wide-open eyes and mouths, a new, unheard-of art makes its entrance in the Rhineland.

Klee himself was catching up fast at the time on the varieties of tyranny. He wrote to his wife, Lily, on 9 February: ‘I am reading (in Mommsen) about Caesar, after having read about Hannibal, and at the same time Stendhal’s Napoleon. Have to be a little while in the company of these kinds of geniuses. Pleasing to note that there are still other formats besides Hitler.’ Pleasing – though not for long. Klee and Lily made a break for Switzerland in December.

‘Bluffs and bewilders’ is the phrase, in the rooms at Tate, that will never entirely go away. It is very hard for us, I have been suggesting, to conjure back the feeling of the circumstances in which, for much of the 20th century, modern art got made. ‘Art Swamp in Western Germany’ may be of use. But even when we have caught a whiff of the savagery, venom and relentlessness that could dog a modernist’s footsteps in Klee’s lifetime, it still needs an immense leap of the imagination if we are to put ourselves in Klee’s shoes – to understand, and maybe to sympathise with, the little creatures scrambling in his labyrinths. Too many adjectives ending in ‘-ical’ – whimsical, mystical, magical, metaphysical – suggest themselves in front of his paintings, and seem to come up as excuses. Maybe because one senses that the ‘-ical’ that matters most to modern art – the physical, the here and now of the painted flat rectangle – is so hard for Klee to hold on to.

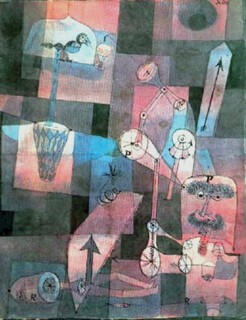

He knew it was. An artist as gifted and intelligent as Klee was must surely have looked back at his first efforts to be a cubist – to spread forms out additively in a rough geometric grid, to stay close to the surface, to have everything in a painting be solid and resistant – and have seen early on how turgid they were, how academic. (An artist’s ability to come to terms with cubism was, for Klee’s generation, the acid test. Klee’s struggle with the style in 1913 is in contrast to Schwitters’s or Miro’s or Mondrian’s, for whom the new idiom is immediately a liberation.) And Klee’s version of cubism was academic – paintings in the show like Plants in the Mountains and Flower Bed are fair examples – because cubist solidity was so remote from his native perceptual habits. It did not take him long to realise that if his art was to flourish he had to work with his very lack of certainty about where anything was in the world and how intimate with objects a painting ought to claim to be. The big animals would sit up at the cubist table; he’d find another way to Buttertown. The mottled, blotted, bending, backlit fields of colour he soon perfected, and the feeling of the surface in a picture (and space in the world) as essentially penetrable – always about to open or dissolve – were his true sensibility discovering its means.

Cubism remained a matrix. Klee realised that others had bent it to their purposes: Mondrian’s sensibility, after all, was as remote from Picasso’s as Klee’s own. In and around 1923 Klee found a way to make even the tight cubist grid do the work he wanted – by inserting enough brighter and lighter squares into the chequerboard, each of them beckoning the eye through the foreground into depth, so that the surface came to look as if it were a kind of transparency ‘really’ hung across a glimpsed infinity on the other side. Once he had the basic idea he often returned to it, varying the size of the squares, the regularity of the grid, the translucency of the veil. The series of glittering watercolours and oils done in 1931 and 1932, using stippled dots or tiny oilpaint tesserae – paintings like Castle Garden or Semi-Circle with Angular Features – strikes me as the high point of this kind of space-making. The Whole Is Dimming (Das Ganze Dämmernd), reads the title of one of them, summing up the vision.

The dimming whole is fragile. Whimsy and weakness are deliberately close much of the time in Klee – because the alternative, in the world of Die Rote Erde, is an undimmable grasp of totality. This is the worldview his art wished to refute.

It is not surprising that in the high age of modernism an art of Klee’s kind was written about superbly. Painting for him was intertwined with language. The rebus and hieroglyph were close. Titles regularly half-enter Klee’s picture space, inked in neatly along the bottom edge, and beautiful in themselves. Word and image are out to seduce us; and yet the best criticism of Klee has been not quite willing to fall under his spell. Greenberg was clearly out to resist. The first version of his great Klee essay appeared in Partisan Review in 1941 – a kind of obituary, written in dark times. The second, published nine years later, from which I have quoted, is crafted with extraordinary tact, but nonetheless seems to be trying most of the time to ‘place’ its object without condescending to him. Compare the inexorable Marxist Otto Karl Werckmeister. He spent long years, in the 1970s and 1980s, pursuing Klee down the alleys of compromise and equivocation that accompany the career of art in our time, and gave us our clearest – and in the end, most compassionate – picture of Klee face to face with war and revolution. We all go to Werckmeister – I do just as much as the writers in the Tate catalogue – for those moments at which, in a letter or scribbled sketch, the Man-Animals come crashing through the Castle Garden walls.

I am not sure the present survey, serious and exhaustive as it is, brings us close enough to the Klee (and the century) these writers are concerned with. The choice of paintings at Tate leans heavily on that made by Klee himself – the works he selected for key shows in Germany and Switzerland between the wars. This has its interest, but in practice I feel that it leads to a muffling and flattening of his art’s experimental flavour. There is a sameness and caution to the canvases displayed, almost at times a kind of stodginess. The rooms have too many ‘exhibition items’ and not enough failures, sidetracks, dashed-off drawings, whimsy tilting towards sweetness or nastiness – which were regularly Klee’s ways of trying to escape from his own good taste. Analyse verschiedener Perversitäten, to quote a nervous title from 1922. Klee’s selections (as with anyone’s) have not always stood the test of time. The clusters of works one comes across in collections put together more recently, by single opinionated connoisseurs – I remember a dazzling room at the Sammlung Rosengart in Lucerne – often seem to me to serve the artist better. I missed Berlin’s incomparable A Child’s Play, and MoMA’s Around the Fish, and stark paintings and pastels from towards the end of Klee’s life: Double, Angel of Death, The Last Still Life.

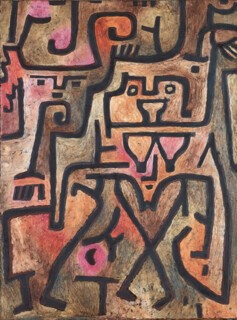

But there are great paintings here. Forest Witches (Wald-Hexen), from 1938, is one of a group of works done in exile where the world left behind, in all its cruel earnestness, is, maybe regretfully, faced head-on. Erd-Hexen from the same year, slightly smaller, moves closer still to the Nazis’ own Brothers Grimm language. Bewitched-Petrified (Verhext-Versteinert), done in 1934, might even be imagining, or hoping for, a Nazism frozen in its mythopoeic tracks. It will continue to be a question, sadly, whether singing fascists their own song in this way ever budged anything (real or ideological) an inch. But Wald-Hexen is a strong work, and makes Klee’s overall attitude to art more comprehensible. The balance he spent a lifetime looking for in his colour and touch, between eerie fragility and just enough decisiveness – insect lightness contending with a half-self-mocking monumentality – was never struck better.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.