The beauty of style indirect libre or free indirect discourse is that it seems to tell the truth without equivocation, to have all the certainty we could wish any third-person narration to have, and then strands us in complicated doubt. Dark clouds ran across the face of the moon; day broke; his teeth chattered; Frédéric bent forward; the parapet was a trifle wide. Straightforward enough. But no, the fifth phrase is surely different, because of the ‘trifle’ (‘un peu’), which suggests a mind making judgments rather than a voice reporting events. Who is saying the parapet is too wide?

We are looking at a paragraph from Flaubert’s L’Education sentimentale, where Frédéric Moreau, standing on the pont de la Concorde in Paris, very briefly contemplates suicide and even more swiftly decides against it. I’ve slightly modified the translation by Douglas Parmée.

Des nues sombres couraient sur la face de la lune. Il la contempla, en rêvant à la grandeur des espaces, à la misère de la vie, au néant de tout. Le jour parut; ses dents claquaient; et, à moitié endormi, mouillé par le brouillard et tout plein de larmes, il se demanda pourquoi n’en pas finir? Rien qu’un mouvement à faire! Le poids de son front l’entraînait, il voyait son cadavre flottant sur l’eau; Frédéric se pencha. Le parapet était un peu large, et ce fut par lassitude qu’il n’essaya pas de le franchir.

Dark clouds ran across the face of the moon. He gazed up at it, meditating on the immensity of space, the wretchedness of life, the emptiness of everything. Day broke. His teeth were chattering; and half asleep, wet from the fog and his eyes full of tears, he asked himself: Why not put an end to it all? One leap would do it! The weight inside his forehead was sweeping him away, he could see his corpse floating on the water. Frédéric bent forward; the parapet was a trifle wide and sheer weariness stopped him from climbing over.

With ‘he asked himself’ we move from declarations about Frédéric and the end of the night to a triple quotation from his mind: why not put an end to it all; one leap would do it; he could see his corpse floating on the water. The intercalated remark about the weight of his forehead might be an authorial enhancement but mainly feels like a more oblique rendering of what Frédéric feels. But then ‘Frédéric bent forward’ is external narration again (he can’t be saying that to himself), and the width of the parapet looks as if it might be a material fact, something you could look up in an architectural guidebook.

For a long time I thought this wonderful paragraph was an instance of Flaubert’s impeccable cruelty towards his characters. ‘A trifle wide’ was a sneer in Flaubert’s own voice, or his narrator’s, and meant that any width would have been wide enough. Frédéric didn’t need an obstacle to prevent him from suicide, since he had no intention of going through with it. And not only was he too trivial to perform this (or pretty much any) act, he was too shallow even to think about it properly, since he allowed himself to blame the structure of the bridge and his own weariness.

I don’t think this reading is entirely wrong, and the last sentence in the paragraph goes some way towards confirming it, since the comment seems both analytical and judgmental. Still, it’s a shortsighted reading and it misses the chief technical achievement of the paragraph, indeed one of Flaubert’s great technical achievements generally, his masterly deployment of style indirect libre. The beauty of this device, as I have suggested, is its apparent lack of equivocation, and we can add the elegance of its grammatical mask: it gives us no sign of whether it is being deployed or not.

In our paragraph, prompted by the interlude in Frédéric’s mind, we ought to be ready for it, or at least ready to entertain the thought of its presence. Then we can read, if I may crudely transpose the process: ‘Frédéric bent forward; the parapet seemed a trifle wide to him and the thought of his own sheer weariness stopped him from climbing over.’ The psychology is not all that different. Frédéric is still not serious about suicide and his weariness still seems to be a name for something else. But Flaubert has disappeared, and with him all trace of moralising. And there is the possibility now that Frédéric is not merely deluded or copping out, but fully aware of the romantic charade he has designed. ‘A trifle wide’ is his own joke. The truth is not that he’s suicidal or failing to be suicidal but that he’s feeling sorry for himself. He’s thinking in clichés (the immensity of space, the wretchedness of life, the emptiness of everything), but they are the best he can do; he’s not a very original fellow. He’s not a fool either, and certainly we can’t expect him to throw himself into the river in a bid for authenticity.

But then none of this is signalled in the prose. All we are told is that the parapet was a trifle wide. There are effects very close to this in Austen, where the characters or the social world occupy, so to speak, the language of the narrator: ‘About 30 years ago, Miss Maria Ward, of Huntingdon, with only seven thousand pounds, had the good luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in the county of Northampton.’ In that sentence ‘only’, ‘good luck’ and ‘captivate’ seem to have crept in from neighbourhood chatter, and if ‘captivate’ means something other than ‘be married to’, it’s slightly at odds with good luck. But we see the occupation and we smile at it, and style indirect libre turns into irony. That’s not quite what libre means in later practice – this is why we need the word ‘free’ in English and why the German term erlebte Rede, ‘animated speech’, isn’t quite right. The important effect is not the animation but the apparent neutrality of the narrative pose. In Flaubert we aren’t even sure the occupation is happening. If it is and we miss it, we have fallen stupidly short as readers, as I did for so long with the width of the parapet; if it’s not there and we find it, we have added free association to our (perhaps) more ordinary style of reading. But even this formulation muffles the deep interest of the device, which is to make us wonder what ‘there’ means in relation to any text.

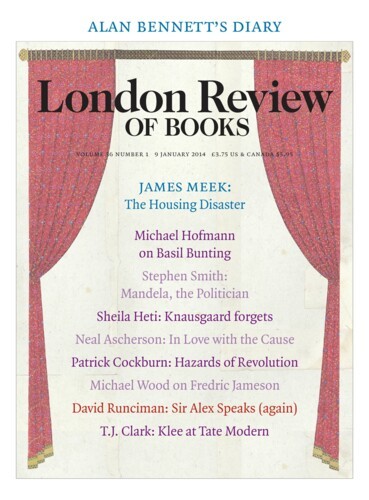

I have lingered over this example because it allows a first approach to Fredric Jameson’s admirable new book by means of something other than a gross and helpless summary. (I’ll get to that in a minute.) Jameson thinks of style indirect libre, point of view and various forms of irony as instruments of the antinomies of his title, ways of doing several things at once. They are also the beginning of the end of the tension represented by the antinomies because ‘the very syntactical machinery that was fundamental to the construction of realism … turns out to participate in its deterioration.’ ‘There thus arises a new kind of multiplicity, not that of objects and sensations, but of individual subjects.’ Of style indirect libre in particular Jameson says: ‘It is an unusual synthesis of third and first person,’ and that is just what it is when it works most smoothly in Flaubert and elsewhere, in Woolf for example: the ‘she’ and the ‘I’ are different but on the same track. But there are also many moments like the one I have described, where the synthesis fails and we flounder between interpretations. These moments confirm one of Jameson’s most subtle and intriguing arguments: that as subjects proliferate the idea of a stable subject disappears. With a first-person narrative we imagine we are standing alongside the protagonist, but we are not: he or she is just a grammatical spot, a place to tell a story from, we are ‘confronted by a mask that looks back at us and invites a trust that can never be verified’. And if this is true for first-person narrative, how much truer must it be for third-person? And when we have both, or may have both, we shall have to wait for our dizziness to subside in order to see where we are.

Jameson says Flaubert is ‘rightly’ regarded as the inventor of style indirect libre and realism. Stendhal and Balzac would be more conventional candidates for the honour, at least in the case of realism, but Stendhal is too quirky and Balzac, in Jameson’s view, is too dedicated to meaning and story. Too dedicated, that is, not for his own good or our pleasure but to be fully invested in realism as Jameson understands it. Paul de Man once said that Georg Lukács wrote about the novel as if he was the novel. Jameson doesn’t do that, but he does write about the novel in terms of a long-standing intimacy with the form, as if it were a roommate, say. This is a report from the interior.

The novel rises in late antiquity, fades away into romance, emerges in Japan and Spain and settles down in France and England in the 18th century. It turns seriously to realism around 1840, and it is in this turn that Jameson finds its conflicted heart. Realist novels want to tell stories, because all novels do; but a story is also a hindrance. It’s too complete, loaded with meaning, always flirting with ideas of doom and destiny, and it lives in the past tense – it’s over before it begins. It needs a liberated partner, and it finds one, precisely, in what Jameson calls affect. In Balzac the liberation is incomplete or the partner abruptly sacked. Of the famous description of the boarding house in Le Père Goriot Jameson says: ‘This description is not the evocation of an affect, for one good reason: namely that it means something.’

A story deals in a ‘named emotion’, while affect ‘somehow eludes language and its naming of things’, allowing realism to set out on an ‘insatiable colonisation of the as yet unexplored and inexpressed’. We are looking at ‘a fundamental feature of modernity, particularly in literature’, the presumption that ‘if it means something, it can’t be real; if it is real, it can’t be absorbed by purely mental or conceptual categories.’ It is worth underlining that for Jameson as for Barthes, whom he cites in this context, this presumption defines modernity because it reflects one of modernity’s cherished beliefs, not because it is sounder than several other presumptions. Barthes writes of myth, illusion and ideology in this context. Still, the lure of the unexplored affect is entirely real, and historical.

Jameson finds affect in the profusion of Zola’s France, the streets, the shops, the light, the crowds, the objects and animals, and his amazing examples – dead fish in a market, an array of cheeses, an ocean of white cloths in a department store – made me feel that Zola was a great writer I hadn’t even started to read. The cheeses are an especially telling (or showing) instance. They appear in tandem with some women gossiping about a man released from prison. The smell of the cheeses is an echo and allegory of the women’s rank talk. But a couple of cheeses would be enough for this, and Zola has pages of them and 18 varieties, from Brie and Géromé to Romantour and Roquefort. The very concept of cheese collapses under the weight of this accumulation of diversity, since it begins to look like an abstraction no one could need.

Affect in Tolstoy appears as a form of distraction. His characters, apparently so solid and stable, are made up of shifting moods, they keep escaping from their story into a landscape of whims, expectations and disappointments. Jameson writes of ‘a gamut of affects … a kind of fever chart or musical partition’: ‘Not the content of these moods but rather their rapid succession is the mark of Tolstoy’s peculiar sensibility.’ The ground shifts for Galdós and George Eliot. In Galdós we witness ‘a deterioration of protagonicity’, whereby the major characters become minor ones, pointing us towards a ‘historiographic context in which … such individualism [the kind that called for major characters and fatidic stories] is no longer meaningful’. Galdós, like Tolstoy, is ‘easily distracted’, that is, happy to give up meaning for the pleasure of inhabiting more and more minds and temperaments.

Eliot’s contribution in this regard is the careful ruin of the distinction between good and evil and the creation of a web of relationships more important than any single element in the configuration. Jameson offers the ‘perverse’ and entirely persuasive argument that Eliot’s ‘moralising style … can in fact be identified as a strategy for weakening the hold of ethical systems and values as such.’ She was Nietzsche’s ally when even (especially) Nietzsche thought she was on the other side. Jameson magnificently calls Casaubon and Bulstrode, in Middlemarch, ‘former villains’, men who came too late in literature for the role they were supposed to play, a little bit like Frédéric Moreau on the bridge. There is more. Eliot has undone the moral binary through a pre-Sartrean interest in mauvaise foi, a condition in which you don’t have to feel guilty, or even be guilty, as long as you can lie to yourself fast enough. This is what she says about Bulstrode: ‘He was simply a man whose desires had been stronger than his theoretic beliefs, and who had gradually explained the gratification of his desires into satisfactory agreement with those beliefs.’ She follows this with one of those grand authorial remarks of the kind that tempt us to write ‘How true’ in the margin. In this case we may not want to write anything. ‘If this be hypocrisy, it is a process which shows itself occasionally in us all.’

Jameson thinks dialectically in the strong sense, in the way we are all supposed to think but almost no one does. This is to say that binary oppositions for him are useful, indeed unavoidable, but meaningless if we don’t see their parts as entangled in each other. The parts are not the same, and there is no middle ground – or if there is, we shouldn’t go there – but their life lies in their relation even more than in their difference. So story and affect, like narration and description, like telling and showing, are twins, and if Jameson spends a lot more time on affect than on story, this is because he rightly thinks we know it less and need help in seeing it. His occasional reminders that we can’t have affect without story can be very dramatic – just when we thought we were getting the hang of things, we learn we have forgotten half of them. The great binary that Jameson sees as the preoccupation of all the writers he cares about and the simplified bane of too much thinking about the world is that of subject and object: why do we imagine we can choose between them, and picture them as inhabiting such different spaces? And there is a wonderful dark dialectical understanding in Jameson’s discreet recall of the dynamics of realism, already evoked: the impulse that gives birth to it will also kill it. Jameson also has chapters on ‘the dissolution of genre’ and ‘realism after realism’, as well as a brief coda on the unclassifiable work of Alexander Kluge, identified for the moment as offering a ‘realism without affect’. This is quite different from the contemporary novel, which Jameson sees as marked by ‘self-indulgent streams of consciousness’ and ‘fragments of an alleged objectivity’, debased inheritors of the story and affect of the tense days of real realism.

The subtitle of Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis, a book put to very good use by Jameson, is ‘The Representation of Reality in Western Literature’. This is a bit mild, deceptively neutral, like style indirect libre. Realism is always a correction, a resistance to other forms of representation; or a plea for unrepresented (scorned, banned, ignored) realities. Realism is also deeply conservative, impatient with realities, or what might be realities, other than its own. This is why Yeats was so ‘disturbed and alarmed’ when, on his father’s urging, he read Eliot. ‘I doubted,’ he said, ‘while the book lay open whatsoever my instinct knew of splendour.’ Splendour for Yeats meant other realities, the possible existence of worlds other than our own. He got over his doubt but it is a tribute to the authority of Eliot’s work, and of realism, that he was so troubled. Jameson makes this authority very clear: ‘The realistic novelist has a vested interest … in the solidity of social reality, in the resistance of bourgeois society to history and to change’; ‘the very choice of the form itself is a professional endorsement of the status quo.’ Of course social reality is pretty solid, and sometimes history and change are on opposite sides. We need to know when the world is not going to get better. But I think also of that terrible moment in Middlemarch where Eliot reminds us of those people ‘who once meant to shape their own deeds and alter the world a little’, but gave up because they breathed in the disillusioned air of practical realism: ‘In the beginning they inhaled it unknowingly; you and I may have sent some of our breath towards infecting them, when we uttered our conforming falsities or drew our silly conclusions.’ ‘It will never work.’ This statement may be true in some cases, even helpful; premature in others; and most often perhaps a form of self-fulfilling prophecy, part of our infinite social plan for making sure that our contemporaries don’t get above themselves. In a world built in part out of such language, style indirect libre itself will not tell us anything – its job is not to tell us anything – but if we know how to read it, to detect it, let it go and put it back, we shall be better equipped to deal with the very idea of alternatives, with pretend certainties and real disappointments.

A last, lighter example from Flaubert, L’Education sentimentale again. The following three sentences end a paragraph about a crowd of jolly people on a steamer going up the Seine: ‘Beaucoup chantaient. On était gai. Il se versait des petits verres.’ In Douglas Parmée’s version: ‘There was a good deal of singing. People were in high spirits. All around, glasses were being filled.’ The first sentence seems simply informative, and the last only mildly ironic in its passive mood – as if no one were doing the pouring, or even the drinking. But ‘on était gai,’ literally ‘one was gay’ or ‘we/they were gay,’ translates what might be a participant’s future narrative of the occasion – ‘comme on était gai ce jour-là’ – into an ostensible detail, like the width of the bridge. We can read it either as the narrator’s laconic judgment on this singing and drinking gang – they were having a good time, if you call that a good time – or as an intrusion of the revellers’ language into the narrator’s, in which case it means something like ‘when we say we’re happy we are happy’ or ‘we have our own ideas of fun and don’t care what any snooty arbiter of good taste thinks.’ The first reading is ironic, the second is just indirect, but the freedom lies in the possibility of hesitation between the two. And we haven’t even to begun to think that the mind inside the narrative voice might also be that of our hero, Frédéric Moreau, a depressed young man on his way home.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.