Portraits – likenesses of living persons – began to appear in China about 2500 years ago. The tradition may be long, but the breadth and scale of the genre are even more striking, especially when portraiture is asked to perform broader duties than the depiction of people. The portrait of a continent is not the same as the portrait of a lady, say, and neither is a ‘portrait of the times’, the title of a vast and dazzling exhibition of contemporary Chinese art – around 120 artists and several hundred works – at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai (until 10 November), a former power plant in Pudong on the banks of the river. Almost all the works address the human figure and many the face itself, so there’s nothing high-handed or implausible about the word ‘portrait’. Nevertheless, like some of the distended, mannerist pieces on display, the very idea of portraiture seems to have undergone an anamorphic twist in order to account for three decades of febrile activity, and it’s not clear what perspective the viewer should adopt in order to cancel the distortion.

Contemporary Chinese art is in the prime of life, a robust, aggressive thirty-something, having settled accounts with the Cultural Revolution, grown bored with politics and appropriated a wide range of late ‘Western’ gallery idioms. Its celebrities have gone eyeball to eyeball with the world’s great collectors: a few years ago when Saatchi blinked, the gallery ended up with a large, mixed-media piece of shit from Liu Wei (Indigestion II, 2004). Despite a recent falling away, China remains the trophy bride of the international art market. The safest option therefore is to position oneself at the far end of this story, roughly a year after Deng became paramount leader in 1978 and opened the way for a revolution in the arts, quite likely the last thing on his mind.

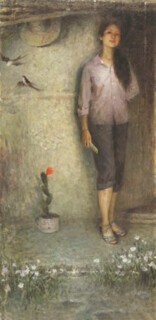

First to the revisionists, survivors of the Cultural Revolution known as Scar artists, who used socialist realism to assess the extent of the damage. In a study of a young woman standing under the eaves of a house – swallows on the wing, wild flowers at her feet, a straw hat hung from the wall – Wang Hai (b. 1955) makes a cool, ambivalent appraisal of student rustication: in this otherwise innocent, even sentimental canvas, we begin to discern a young exile from the city, one of millions banished to rural areas. Students are also the subject of a breathtaking narrative oil painting by Cheng Conglin (b. 1954) which dramatises the return to an exam curriculum in 1977, the year after Mao’s death. Wang’s Spring was painted in 1979; Cheng’s Summer Night: The Days of Restoring the College Entrance Examination was finished in 2009 and gives Scar art a respectable claim to longevity. (Scar literature, so-called after a story by Lu Xinhua in 1978, was short-lived, but recycled post-mortem in works like Wild Swans, aimed over the heads of mainland readers at the international market.)

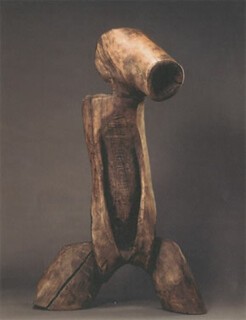

The Scar movement came to prominence at the same time as the Stars Group. Stars luminaries included Ma Desheng (b. 1952), Wang Keping (b. 1949) and Ai Weiwei, who doesn’t put in an appearance. Ma features with a group of expressionist woodcuts from 1979 and 1980, when the Stars were on the streets of Beijing demanding greater artistic freedom, Wang with his elemental wood sculptures, including Big Mouth, an anthropomorphic megaphone carved at the end of the 1980s. After a serious tussle with the authorities, the Stars were eventually allowed a two-week show at the China Art Gallery, now the National Art Museum of China, in 1980; their work drew nearly 200,000 visitors.

Few of the Scars and Stars on display in Portrait of the Times seem to have redesigned themselves as part of the 85 New Wave Movement, which broke in the mid-1980s with a flurry of exhibitions, debates, manifestos and critical texts: Scars couldn’t or wouldn’t and Stars, perhaps, didn’t need to. But at least one of the New Wave painters here, Wang Guangyi (b. 1957), slid effortlessly from New Wave into Political Pop, the über-Warhol style that took off after a Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange show in Beijing in 1985. Other New Wavers went the same way and within a few years Political Pop was garnering enormous interest in Hong Kong, Sydney, Melbourne and, in 1995, at the Venice Biennale. Wang quickly became a superstar with his Great Criticism series, juxtaposing the command-imagery of the Maoist poster with the autistic writ of Western consumer brand names: Porsche, Coca-Cola, Chanel, Gucci. Wang’s big work on show here is Great Criticism – Time (c.1998).

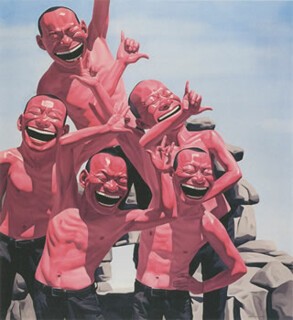

The other thread in this, the penultimate phase of the story, is Cynical Realism, which peaked about six years after Tiananmen but hasn’t yet had its day. More prized by foreign investors than the Popists, the Cynical Realists are clever and captivating, standoffish and garish by turns. Their disenchantment with politics is matched by their reservations about apolitical consumerism, an uneasiness which speaks to our own sense of gratified ambivalence and makes them some of the richest artists on earth, whose work we’d recognise as easily as Wang Guangyi’s even if we couldn’t put a name to it: Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang and Zeng Fanzhi are well represented in this exhibition (see below).

Which brings us up to the present phase: market consolidation. In 2002, according to the BBC, Chinese contemporary art in various guises fetched a total of one million US dollars at auctions around the world, a figure that grew to $167.4 million by 2010. But what of labelled price sales at art fairs and direct acquisitions by galleries? Three hundred million could be a conservative estimate for recent work changing hands on all available trading platforms two years after the banking meltdown. In the view of researchers at the European Fine Art Foundation, the Chinese market share is far higher: they put the global value of the art market in 2011 at about $60 billion and found that Chinese art accounted for 42 per cent of auction sales, themselves worth roughly half of all transactions. The volume of contemporary Chinese art in this breakdown is hard to ascertain, but even at a fraction of total Chinese artefacts exchanged, the figure of $300 million looks very low indeed. China is still singing. Increasingly this has to do with a new millionaire class of domestic investor. A few years ago a signature piece could sell in the West for ten times the price it fetched at home. The gap is closing. Is that good or bad for the artist and his entourage? It depends on prices abroad and domestic confidence in the resale value of the product. Either way, the struggle is on to keep price tags and opinions tuned to current levels without something snapping.

With the story moving at breakneck speed, a sequential account of schools and fashions is risky: there’s always the unpleasant suggestion of something having died in the corner, extinguished by a ruthless successor. Better to keep as much material, and as many reputations, up in the air as possible. In any case there is very little guidance on the chronology in Li Xu’s brilliant curation, the first fully homegrown show at the old power plant since it opened last autumn as China’s first state-run contemporary art museum. Instead the cataract of works is distributed by theme: ‘Specific Individual’ (‘from “we” to “I”’), ‘Body Language’, ‘Images of Society’ and so on. In a show of this size, the delegation of pieces to themes can seem arbitrary and the themes themselves porous, but the result is more comprehensive than it would have been as an orderly retrospective: so many of the artists have no place in the main groupings that swept in after Deng’s reform.

The other advantage of theming is that works which have no obvious affinity are surprised in unlikely encounters, only occasionally embarrassing. The third section of the show, ‘The World Within’, is typical. On the one hand, there are quietist pieces by Zhang Jian and Jin Weihong, both Nanjing fine arts graduates, both in their forties, both committed to the traditions of ink on paper and ink (and colour) on silk, Zhang with his stylised courtesans, Jin with her reticent female figures stranded on pale washes. On the other, there are brash, expressionist oils by Zeng Fanzhi (b.1964), including work from his Mask Series done in the 1990s: these ambitious studies of alienation as such, rather than the alienated subject, are top of the range pieces: Mask No. 6 sold for $9.7 million at Christie’s Hong Kong five years ago. Oddly, Yue Minjun’s inane grinning men are also assigned to ‘The World Within’. They are masks in their way, only more disturbing than Zeng’s. Behind the rictus grin of self-satisfaction there seems to be no living occupant and so, by extension, no prospect of an apprehended world: the ground in Yue (b. 1962) can be as vacuous and stylised as the figures. Satire of a deadly order is a better description than ‘cynical realism’. One of his earlier pieces, a brilliant, farcical-grotesque restaging of Manet’s Execution of Maximilian, sold for £2.9 million in London before the crash.

Elsewhere in ‘The World Within’ there are impressive, unpretentious shows of skill, including a set of oils by the faerie-Daoist Zhang Jianjun (b. 1955), a master of imagined moonscapes with figures: Delvaux is Zhang’s next of kin in the Western canon, though Zhang is the better painter. Two nostalgic bedroom scenes in oils, lit and executed in the manner of Renoir, introduce us to the academic realist Chang Qing (b. 1965), who can also manage a beautiful, Oriental Chardin, plus any amount of well-managed schmaltz: a reactionary without a cause, and in spite of himself, in a world where rebels, reactionaries and causes no longer count for much.

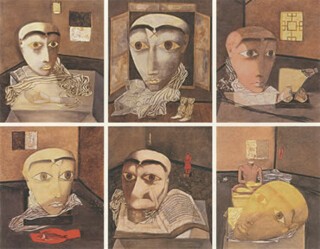

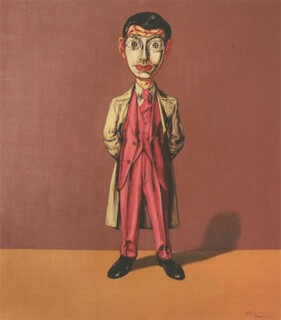

For the novice two works in this section stand out. The first is a suite of six heads in oil and pencil with detached body parts by Zhang Xiaogang (b. 1958, highest sale price $10.1 million in 2011). Zhang is famous for his imagined family groups – communism is the shared DNA – whose members gaze out wistfully from somewhere on Planet Mao (Big Family – Subway, 2004, is allocated, oddly again, to ‘The Specific Individual’). But Series of Abysses 1-6 is a more arresting sequence, with its late Orientalisation of Klee and its staging of a corps morcelé within a single, secluded space with walls and a floor: defined interiors of this kind are rare in the paintings on show. The second is the record of a tour of the provinces with a mobile photographic studio in a truck – plentiful backdrops, props and a set of theatre curtains – by Ma Liang (aka Maleonn, b. 1972), a designer by training. Ma’s work is among the most delightful in the show. His sets are lovingly painted and his subjects, mostly posing in costumes, are wholly engaging, as Supermen or samurai or a pair of pilots in a toy plane. Unlike Zeng’s masks and Yue’s enormous, leveraged smiles, permanently fixed over a worrying void, the costumes and mises-en-scène in Ma are trappings in a lavish role-play: transparent, reassuring, removable above all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.