Self-Portrait as Picture Window

First day of snow, the low sun

glinting on the gate post where a single

Teviot ewe is licking

frost-melt from the bars, the other sheep

away in the lower field, the light on the crusted

meadow grass that makes me think

of unripe plums so local an event

it seems, for one long breath,

that time might stop;

or, better, that it isn’t me at all

who stands here, at this window, gazing out,

not me who woke up late, when everyone

had gone to work or school, but someone else,

a man so like myself that nobody

would spot the difference – same eyes, same mouth –

but gifted with a knowledge I can scarcely

register in words, unless I call it

graceful and nomadic, some lost art

of finding home in sheep trails, lines of flight,

the feel of distance singing in the flesh,

that happiness-as-forage, bedding in,

declining, making sense of what it finds.

Peregrines

Soon they will kill the falcons that breed in the quarry,

(it’s only a matter of time: raptors need space

and, in these parts, space equals money);

but now, for a season, they fly low over the fields

and the thin paths that run to the woods

at Gillingshill,

the children calling out on Sunday walks

to stop and look

and all of us

pausing to turn in our tracks while the mortgaged land

falls silent for miles around, the village below us

empty and grey as the vault where its money sleeps,

and the moment so close to sweet, while we stand and wait

for the flicker of sky in our bones

that is almost flight.

Choir

I think, if I tried, I could go back and sing again

no worse than I did at twelve, when my voice broke too soon

and I moved to the back of the choir on practice days,

mouthing the words and hoping that no one would hear

the missing soprano.

I stayed for the sudden dark at the stained glass window,

the sense of a vigil it gave me, like waiting for snow

at the presbytery door, a shape stealing in from the cold

to claim me for some lost kingdom; I stayed for the candles

and, off to the side of the altar, the theatre of absence

that made more sense, to me,

than our Sunday School God.

Close to retirement, the choirmaster hammered away

at the upright piano,

not for a moment

deceived, so much

in tune with us, he knew each voice by name,

the way a herdsman knows his animals:

the Cunningham twins, their faces so alike

that no one could tell them apart, until they sang;

the Polish boy, Marek; the grammar school beauty who smelled

like cinnamon after the rain

– he knew us all by heart, each voice he heard

combining with every child he had taught to sing

through a lifetime of choir, so thoroughly rehearsed

he swore he would pick us out

on Judgment Day.

I turned up every week for six months more;

and all that time he kept

my secret, each of us

pretending not to know the other knew.

I mouthed the words; he played; nobody guessed,

or everyone did; it doesn’t matter now.

Later I switched to blues and the Rolling Stones,

Mandies and cider, Benzedrine, Lebanese;

so, though I wanted to, I couldn’t

make it to Our Lady’s on the day

they buried him next to his wife, in the steeltown rain,

to prepare for the Second Coming; and anyway,

despite the years of Kyries and hymns,

I never quite saw the point

of the life to come; back then it seemed

that, like as not, most everything runs on

as choir: all one; the living and the dead:

first catch, then canon; fugal; all one breath.

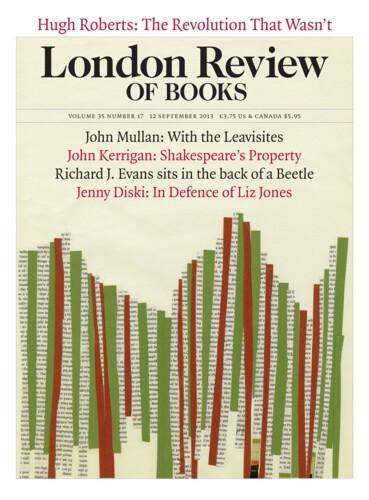

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.