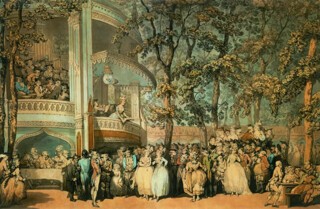

Eighteenth-century historians can’t get enough of pleasure gardens. They seem to crystallise the new and distinctive features of Georgian society and culture in one fabulous setting. As places of commerce masquerading as wooded groves, pleasure gardens offered idealised rus in urbe. They could seem poetic in the dusk as the visitor listened to the evening chorus of resident songbirds, but were transportingly magical as night fell and hundreds, if not thousands, of lights were illuminated in the trees and colonnades. We are so accustomed to electricity that it is difficult to imagine the thrill of these oil lamps in an era when most relied on the fire in the grate and a smelly tallow candle to hold back the night.

For the price of a ticket, one could enjoy musical performances and refreshments al fresco, or simply see and be seen. Princes rubbed shoulders with prostitutes, duchesses with doctors’ daughters: the social mix was a large part of the gardens’ attraction at the time and our fascination with them now. They seem to have epitomised the comparative openness of a polite and commercial people addicted to congregation, artifice and performance.

Unsurprisingly, the most famous pleasure gardens were in London. Vauxhall, Ranelagh and Marylebone are the three best known, though there is evidence that at least 64 metropolitan venues were in business between 1661 and 1871. Outside London, urban pleasure gardens such as Spring Gardens in Leeds (in existence from 1715), Spring Gardens in Bath (from 1742), Moore’s Spring Gardens in Norwich (1750s), Vauxhall Gardens in Bristol (1750s and 1770s) and the New Ranelagh Gardens in Newcastle (1760) were quite staid, drawing in socially more homogeneous customers from the provincial gentility.

Private pleasure gardens attached to noble houses and royal courts have a long history, but Vauxhall Gardens, which opened on the South Bank of the Thames in 1661, might well have been the first commercial pleasure garden in Europe. The business flourished for two centuries, finally closing in 1859. Vauxhall’s special status, Alan Borg and David Coke argue in this hefty antiquarian tome, lies in its originality as a commercial venture, the changes it triggered in the social and cultural life of London, the extreme heterogeneity of the mingling crowds, the mass audience the gardens gave to modern music and popular song, and the revolution it triggered in mass catering and outdoor lighting. In the architecture of the garden buildings, the design of the interiors and the painting and sculpture it showcased, Vauxhall was, they claim, ‘the first true public gallery of modern British art’. It was also the site of patriotic pageants and jubilees, offering damp, chilly Albion its version of the carnivalesque: ‘anarchic, tumultuous, youthful, thrilling, kaleidoscopic and, for most people, totally foreign to their day to day lives’. Venice-on-Thames.

The royal parks, such as St James’s and Hyde Park, began opening to the public in the 17th century, while places like the Bear Gardens south of the river offered food and music, as well as bear-baiting, to more unruly customers. But the observant would have noticed something rather different about the Spring Gardens, as they were originally known, at Vauxhall. John Evelyn, an early visitor, described the site in July 1661 as ‘a pretty contriv’d plantation’. The trees there were said to be a hundred years old in 1661. The gardens offered ‘a universal withdrawing room for the city’, as Borg and Coke put it, the impression of separateness emphasised by the fact that until Westminster Bridge opened in 1750 most visitors got there by boat. The site was carefully chosen: the South Bank had a long history as a site of commercial entertainments; the river was the chief thoroughfare in the city; and Vauxhall was conveniently close to the market gardens of South London and safe from the stink of the city. Pepys mentioned Vauxhall in his diary 23 times between 1662 and 1668. He wrote about the arrival by river, the expensive food, the nightingales singing, the acrobats and fiddlers and the entertainers who made animal sounds, the arbours for romance and the drunken groups of men pestering pretty women.

The sexual opportunities associated with the gardens were well established by the early 18th century. Addison and Steele had their loveable curmudgeon Sir Roger de Coverley harrumph that he would be a better customer if Vauxhall offered more nightingales and fewer strumpets. A Virginian gentleman called William Byrd was matter of fact about the amenities in June 1718:

We went to Spring Gardens where we picked up two women and carried them into the arbour and ate some cold veal and about 10 o’clock we carried them to the bagnio, where we bathed and lay with them all night and I roger’d mine twice and slept pretty well, but neglected my prayers.

The reputation of early 18th-century Vauxhall meant the gardens did not attract well-bred female visitors, and without such ladies the gardens could never be fashionable.

All this was to change under the proprietorship of Jonathan Tyers, a Bermondsey tradesman who managed to conceal his background in the leather industry and project himself as a man of learning and culture, establishing his family as lesser gentry in Surrey. He took on the Vauxhall lease in 1729, at the age of 27, and went on to buy half the estate outright in 1752. Tyers emerges as both libertarian and moraliser. He admitted anyone who could stump up sixpence for a ticket, excluding only servants in livery, on the grounds that livery would encourage segregation. He tried to stamp out public depravity by employing his own constables. His aim was to draw the carriage trade by establishing the gardens’ reputation as a place for innocent amusements and prestigious cultural entertainments.

The gardens were fashionably refurbished. Tyers commissioned a series of garden buildings, including theatres, and a new colonnade of supper boxes. The first buildings were in the Palladian style characteristic of the Whig aristocracy, but from the 1740s there were ‘Chinese’ pavilions, rococo follies and the so-called Turkish tent (an outdoor dining hall). The tent struck Fielding in 1742 as ‘a Pavilion that beggars all description’, somehow uniting fancy and dignity:

I do not mean for the Richness of the Materials, of which it is composed, but for the nobleness of the Design, and the Elegance of the Decorations, with which it is adorn’d; In a word, Architecture, such as Greece would not be ashamed of, and Drapery, far beyond the imaginations of the East, are here united in a Taste that, I believe, never was equall’d nor can be exceeded.

Hyperbole notwithstanding, this fusion of the exotic and familiar gave Vauxhall much of its aesthetic appeal. The grove – the central area of the gardens – reminded visitors of Covent Garden, or even St Mark’s Square. Garden buildings may be ephemeral, but with tens of thousands of visitors each season the orchestra building, the rotunda and the pillared saloon were some of the best-known examples of modern architecture in the country. Vauxhall became a showroom for British architecture and interior design. Exhibiting modern art was another way to increase cultural cachet. Tyers commissioned Francis Hayman and Hubert-François Gravelot, who illustrated Richardson’s Pamela, to create fifty large genre paintings to be hung in the supper boxes that surrounded the grove (the punishment the pictures took from weather and food was severe).

Vauxhall’s main attraction was musical performance. English-based composers and performers, Handel especially, were favoured. A great crowd gathered to hear the rehearsal of Handel’s music for the royal fireworks on 21 April 1749; there was a three-hour traffic jam on London Bridge. Borg and Coke make the original point that it was the informality of the recitals that made them successful. The audience could drift in and out, a freedom that ‘led to a much wider and easier acceptance of concert as a public entertainment’.

Vauxhall in its heyday was both nursery and epitome of the rococo, which Borg and Coke characterise as ‘a creative reaction of youth against authority’. The rebels included the gardens’ patron, Frederick, Prince of Wales, the artists Hogarth and Hayman, the designers Gravelot and George Michael Moser, the sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac and the composers Arne and Handel: ‘The brash light-heartedness, the unwillingness to follow rules, the energy, informality and experimentation that were intrinsic to Vauxhall are all typical of the English rococo.’

If any single event typified the pleasure garden it was the Ridotto al Fresco. For the grand opening of his refurbished gardens in 1732, Tyers hired an impresario called John James Heidegger to stage ‘a ball in the Italian manner after their carnivals’ – essentially, outdoor dancing in masquerade costume. At a guinea, the cost of tickets was prohibitive for most, but the attendance of the Prince of Wales with noble entourage and between three and four hundred well-dressed guests was a propaganda coup. A summer evening at the gardens became a fixture of the season. As the commentator William Horsley remembered in a collection of essays published in 1748:

I believe a man need not be very old to remember when Vauxhall Gardens were in a state of nature unembellished with lights, Tents, paintings &c. and then but moderately frequented, nor when by the Address of my brother H[eidgge]r they first began to shine, sparkle and draw thither numberless admirers.

Vauxhall was a triumph for an early version of PR. The marketing and publicity campaign was multi-layered. First, Tyers mythologised the gardens, promoting the vision of a dreamlike Elysium for weary Londoners. The theme was carried through in the art he commissioned and elaborated in songs, as well as in flattering essays and histories, many by the poet and librettist John Lockman. Tyers addressed his audience as ladies of quality, patriots and educated people – those who appreciated the finer things – and kept up a stream of information about the history of gardens and forthcoming attractions. Another marketing ploy was the withdrawal of paper tickets in favour of silver season tickets to appeal to the vanity of the well-heeled, excluding those who were ‘in no way qualified to intermix with persons of better Fashion’. The famous Vauxhall songs – devoted to love, manners and fashion – seemed contrived to ventilate female concerns. The authors detect a feminine bias in much of the marketing, and argue that Tyers had the wit to target the underexploited women’s market for culture and consumables.

Portraying the gardens as a safe and respectable place for decorous women to visit was central to Tyers’s strategy. But it would have taken many more constables than he was prepared to employ to banish prostitution and illicit sex altogether, especially on the notorious ‘dark walks’. Northern tourists worried about the possible dangers associated with large crowds of strangers. Masquerades were a particular concern: the anonymity was thought to encourage social and sexual chaos. The Bishop of London had preached against masked balls in 1724 and George II made an ineffectual attempt to have them suppressed. Yet the popularity of the balls was hardly dented: a little controlled risk, it seems, only added to the frisson.

The dramatic possibilities of all this weren’t lost on writers of the time. Fielding’s Amelia is mistaken for a courtesan at Vauxhall, despite being chaperoned by a churchman and two small children. Fanny Burney’s ingenuous 17-year-old heroine Evelina is drawn down one of the dark walks, possibly the notorious Lovers’ Walk, and importuned by parties of lewd men. The pleasure garden became shorthand for sexual intrigue, adventure and danger. Tyers may well have played up the air of peril to give a bit of edge to what was little more than a stately evening promenade around a dank park.

We don’t have reliable attendance figures, but a thousand visitors a night seems a plausible estimate. All the anecdotes about heaving crowds support the conclusion that Vauxhall was the most popular single visitor attraction in mid-18th-century London. But it was not unchallenged. There were scores of other pleasure gardens, many of them just a garden attached to a spa, each with its own gimmick (from the equestrian displays at Dobney’s Bowling Green to the pebble mosaics at the Spaniards in Hampstead), but only Marylebone and Ranelagh were a serious threat to Vauxhall.

Marylebone Gardens established a reputation for superior music, had the advantage of ‘mineral wells’ on site and staged firework displays from as early as the 1760s, decades before Vauxhall. Nevertheless it became known as a haven for cardsharps and despite a run of startling entertainments in the 1770s, from a re-creation of the eruption of Mount Etna to a reconstruction of Paris, it closed in 1778.

Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea opened in 1742 and was a more worrying competitor. It was more exclusive than Vauxhall – at half a crown, the admission fee was correspondingly higher – and much nearer the new West End. It rapidly became the more fashionable resort. A doctor’s daughter called Jane Pellet reported in 1743: ‘Among the people of Tast le Delicatesse I think Ranelagh is now the darling pleasure for the sake of Mr Sullivan, who sings the “Rising Sun” & “Stella & Flavia”.’ The visitor was at liberty to wander about admiring the Chinese buildings, the canal and the bridge, and to take a turn around the rotunda, a vast circular hall inspired by the pantheon in Rome. The rotunda was a marvel inside and out, putting observers in mind of a giant lantern radiating light across the bosky gardens. It ensured the attractions of Ranelagh were weatherproof; rain was the bane of Tyers’s commercial life. However, Ranelagh’s exclusivity and respectability (strong liquor and gambling were banned) meant that it was never as exciting as Vauxhall. The fashionable had deserted it by 1780, though it hung on until 1803.

Vauxhall survived the death of its great entrepreneur in 1767, and a bumpy ride under the management of his son, and remained a going concern for another ninety years. However, by the 19th century, it had become more like a circus than a sylvan retreat: new attractions included firework displays, ballooning, sailing races, a new theatre for ballet, a high-wire act, bareback riders and lion-tamers. Though Wordsworth was still dazzled at the age of 18 by the ‘wilderness of lamps dimming the stars’, the pastoral idyll had faded. The novelist Edmund Yates remembered that by the 1840s ‘it was a very ghastly place: of actual garden there was no sign.’

Borg and Coke’s meticulous chronological narrative is the first book-length study of Vauxhall in 55 years, but extracting an argument from the blizzard of information takes painstaking effort. The book is indifferent to recent work contesting the claim that what went on beneath the trees amounted to social revolution. The mingling of princes and paupers was much exaggerated by critics at the time, as it has been by many historians since. Dilution by the vulgar killed the fashionability of a resort. Even in Bath, Smollett’s Matthew Bramble complained, ‘a very inconsiderable proportion of genteel people are lost in a mob of impudent plebeians.’ Hence the continued attempt to demarcate exclusive space – the beau monde commandeering the front-facing supper boxes – within pleasure gardens, and the use of devices which limited the access of the vulgar: subscription, dedication and charity.

Hannah Greig’s research on the elite experience of pleasure gardens shows that the nobility liked having an audience but drew the line at fraternisation.* Greig cites the complaints of a Yorkshire gentleman called Godfrey Bosville in 1765:

We go here to Publick places but though we do it is but a public life in appearance for everybodys Conversation is in a manner confined within the Compass of a few particular Acquaintance. The Nobility hold themselves uncontaminated with the Commons. You seldom see a Lord & a private Gentleman together. An American that saw a Regiment of footmen drawn up might think the officers & soldiers mighty sociable. Just so is the company at Soho Square altogether and all distinct.

She concludes that

the pleasure garden as a melting pot was a powerful metaphor deployed by satirists, but there are few traces of social mobility and vibrant social mingling in the accounts of those who went there. Indeed, the titled made few concessions to the new cast of bourgeoisie. The appearance of public togetherness disguised a reality wherein the titled lady dismissed the wife of a city merchant and the wealthy Yorkshire gentleman rarely conversed with a lord.

Vauxhall might have resembled an enchanted wood, but prince and pauper knew their place, even in fairyland.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.