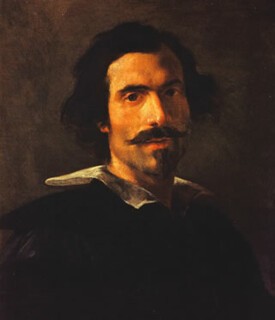

Franco Mormando has a lot to tell us about Gian Lorenzo Bernini and the Rome of his day, but one lasting lesson is that just about everyone who knew him hated him. The harshest criticism came from his mother, who in 1638 wrote an exasperated letter to Pope Urban VIII’s nephew, Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Bernini had got into a murderous rage when he discovered that his lover Costanza Bonarelli had been having an affair with his brother Luigi. After chasing Luigi into St Peter’s and breaking a couple of his ribs, Bernini resumed the chase, sword in hand, to Santa Maria Maggiore, where Luigi found refuge. A henchman was dispatched to slash Costanza’s face. Mormando’s translation of the letter stiffens somewhat the heated formality of the Italian: ‘His sense of power, it seems, has today reached such a degree whereby he has no fear whatsoever of the law. Indeed, he goes about his affairs with an air of complete impunity, to the great sorrow of his mother and the marvel of all Rome.’

Unfortunately for his mother, Bernini’s employers were both impressed and amused by his ruthlessness. Cardinal Francesco was loyal to his court artist, and that year suppressed the publication of a satire accusing Bernini, then in charge of construction at St Peter’s, of gross architectural incompetence. Bernini’s immunity was an extension of the privilege accorded the gallery of rogues who populated the world of his patrons. Scipione Borghese, Bernini’s first great supporter and client, persuaded his uncle Pope Paul V to make his lover Stefano Pignatelli a cardinal; and Antonio Barberini, Pope Urban VIII’s notorious nephew, was made a cardinal at the age of twenty, to howls of protest, and proceeded to populate the family palace – now famous for its collection of paintings and its frescoes by Pietro da Cortona – with hustlers and young lovers.

The most passionate haters were Bernini’s fellow artists. When he wasn’t subcontracting work to them and passing it off as his own, he was deploying a network of highly placed officials and, occasionally, thugs to ice them out of commissions. The astonishing handling of the various changing textures – leaves and twigs out of hair and flesh – in the Apollo and Daphne in Rome’s Borghese Gallery, uniformly ascribed to Bernini, was done by the brilliant young sculptor Giuliano Finelli. Even in his twenties, the wildly successful Bernini was developing the Bernini brand, which could easily absorb the work of other artists.

Rubens was doing the same thing around the same time, and Titian and Raphael had done it earlier. But the persistent sound of gnashing teeth in the records suggests that Bernini had a uniquely poisonous way with collaborators and colleagues. Raphael’s pupils continued to revere him after his death, even as they went on to become some of the most successful artists of the next decades. Van Dyck manoeuvred himself out of Rubens’s workshop and shadow while maintaining good relations. But Finelli was so disgusted that he severed all ties with Bernini in 1629, effectively consigning himself to the oblivion where he languishes today. Francesco Borromini, a superior architect whom Bernini employed at St Peter’s for the expertise he himself did not possess, never forgave Bernini for taking the credit due to him for the great bronze baldachin over the basilica’s high altar, and eventually committed suicide in despair at his thwarted life. The only artist to hold his own in Bernini’s sphere was the painter and architect Cortona, who was Bernini’s match in ruthlessness. The contemporary sculptor Orfeo Boselli said that the two of them were ‘the most insatiable politicians ever in this business, because they keep away all those who can work on a level equal to them, and they give opportunities to work either to those who depend on them or to their pupils and eulogists.’

What we know about Bernini comes primarily from two biographies, one by Filippo Baldinucci published in 1682, shortly after Bernini’s death, and one by the artist’s son Domenico published in 1713 (though, Mormando contends, written long before and in fact Baldinucci’s source). The other major source, also friendly to Bernini, is the account of his 1665 trip to France by the connoisseur Paul Fréart de Chantelou, which contains many of the artist’s sayings and reflections on his own life. The two biographies tell the story of a prodigy recognised as the future of art from the moment of his arrival in Rome in 1606 at the age of eight. They chronicle his early work under Borghese and his extraordinary success as the court artist to Pope Urban VIII and the Barberini family. Both do a great deal to whitewash Bernini’s youthful unruliness and romances (his fiery temperament fuelled his devotion to his work), while insisting on his great piety after his marriage in 1639 at the age of 41 (‘from that hour he began to behave more like a cleric than a layman,’ Baldinucci says, implausibly). In both books we hear about his struggles under the less than benevolent Pope Innocent X, from whom he nonetheless won the commission for the Four Rivers Fountain (1648-51) by having his silver model for the project placed in a room through which the pope was expected to pass. (‘Anyone who does not want to use Bernini’s designs must simply keep from even setting eyes on them,’ Domenico has Innocent remark, as if the pope were given to public pronouncements about his own hostility to the artist and his inability to sustain it.) Baldinucci and Domenico rejoice at the master’s return to favour under the construction-happy Pope Alexander VII. Domenico insists on the signal honour of Bernini’s invitation to the court of Louis XIV during the summer and autumn of 1665, and claims that the artist’s embassy was a condition of the recently concluded peace between the papacy and the French crown, insisted on by the king himself. But they downplay the rejection of Bernini’s plans for the Louvre and the cool parting that followed. Both biographers write glowingly about the artist’s pious and stoical old age and death.

If there’s one artist whose work needs to be understood in the context of real life (and realpolitik), it’s Bernini. Mormando, a historian of 17th-century Rome, ably corrects and contextualises the early biographies and is careful not to fall prey to their promotional agendas. But his book is not a revisionist polemic. Bernini’s faults and the cruelty and duplicity of his world are presented as features of the carnival that was Baroque Rome. Mormando’s tone remains buoyant and homey (not to say hokey) throughout: ‘Ah, the fickleness of love and hate in Baroque Rome’; ‘Bernini may have been expert in the carving of angels, but he was far from one himself.’ The account is pegged to the works of art, presented more or less in chronological order, but Mormando is clear that he is writing a biography, not art history. He is at his best when presenting the relevant facts about each commission and contemporary reactions to the works and at his worst when telling us that ‘we must again at least raise – with all due restraint – the issue of Bernini’s own libido’ to understand his art.

Still, the evidence Mormando puts before us – the violence, the backstabbing, the family mafias, the scandals, the cover-ups and the critical voices exposing it all as it happened – is the atmosphere Bernini’s art flourished in. Mormando is right to insist on the importance of the capacity for dissimulation, the courtly art of saying what people want to hear. Dissimulation, Mormando writes, was ‘an essential item in the survival kit of the courtier’ – and ‘survival’ was not a metaphor. As we read in a letter to Ferrante Pallavicino, a writer of popular political satires, ‘the ink of those pens that are not used to celebrate’ the names of the powerful ‘usually ends up mixed with blood’. Not long afterwards, Pallavicino was beheaded by order of Urban VIII, Bernini’s greatest patron. In the same year, Milton lamented ‘the servile condition’ that had ‘damped the glory of Italian wits’. ‘Nothing,’ he wrote, ‘had been there written now these many years but flattery and fustian.’

Bernini did more than survive. He thrived, not because he was a master of fustian (he wasn’t) and not merely because he knew how to flatter. His art, which shows figures swept up by forces larger than themselves, made power relations appear part of the natural order of things. The subjects (rape, rapture, grace-filled angels, and those invested with earthly power) co-operated readily enough. But the profound message – that real power is ennobling, more beautiful than nature, and irresistible – runs through the work, regardless of subject. Beyond representing emblems of power, this art offered repeated demonstrations of the way power moves through the world. It showed the absolutists how absolutism was supposed to work. Whatever the populace may have thought, the ideology implicit in Bernini’s art was an intoxicant to those giving the commissions, who could only wish that their power was this sweeping and unanswerable. Moreover, and almost as a consequence, Bernini’s artistic domain was extendable, capable of assimilating individual talents into the larger statement, a feat that could only impress patrons such as his. Rubens’s large shop also served princes and also ably extended his brand, but there the result was a spreading of ‘Rubensian’ painting. In Bernini’s case, the principle of extension produced something beyond him: the concept of Baroque art would probably never have gained coherence without the galvanising effect of Bernini’s ubiquitous activity in Rome.

The key to all this was the notion of artistic style, an idea absent from the artistic world of antiquity (though that did not prevent art historians, beginning with Winckelmann, from organising ancient art according to stylistic categories). The concept of style held that a work of art by a given artist or of a given time or place has an identifying quality that runs through it, characterising it in its totality and its parts. Bernini didn’t merely adapt or develop a style. He elevated style to a principle. Much of what we consider typical of Baroque art follows from this basic move. Classicism, which aspires to an ideal truth that is by definition styleless, finds stillness even in movement (Reni, Poussin), but an emphasis on style will tend to exaggerate movement as a form of signature or flourish. In its insistence on a consistent impression it will tend to stress perceptual unity rather than isolated units: it will insist on atmosphere. Since it is something that runs, mysteriously, through different works and across media, it will tend to favour the integration of the arts, what Bernini called the bel composto. Accompanying these developments is a general increase in scale. Orthodoxy, here, is not a catalogue of rules and doctrines but a form of life, a way of being in the world. Bernini lived before art for art’s sake but he was part of an emergent art world, newly equipped with an art theory, an art market and a pantheon of artists. That art had come into its own, and that it was a kingdom of style, was, Bernini saw, the key to its political and religious charisma.

Bernini’s four and a half metre tall St Longinus, in the first pier on the right as one approaches the crossing of St Peter’s, looks up in recognition at the crucifix topping the great baldachin over the high altar. According to post-biblical legend, this was the soldier who pierced Christ’s side and then was converted by the blood and water that spouted from it, declaring: ‘Truly this was the Son of God!’ In response to the brutal wound he has inflicted on Christ’s corpse Longinus receives a baptism more powerful than any weapon’s blow. His gesture is not an action but a reaction, not only in his outstretched arms but in every aspect of his form, organic and inorganic. His slashed epaulettes bounce in sympathy with the ringlets of his hair and beard. The folds of his cloak turn and curl independently of the body, as if directly enlivened by the heavenly influence thrumming through the figure as a whole. The roiling folds rhyme with the agitated swirls of the red and white marble panels behind the statue, suggesting a force affecting the whole environment – perhaps the violent storm and earthquake the gospels describe at the moment of Christ’s death. For Bernini, the subject isn’t St Longinus, but the effects of an absent but enthralling power, actively revealing its signature in things. The subject is the world turning into a work of art under the effect of that power.

‘Who in the domain of the plastic arts has moved and delighted people more than Bernini?’ Nietzsche wrote, not out of admiration but to illustrate the principle that highly affecting art is not necessarily good art. Far from showing that the people were entertained, the contemporary records, amply adduced by Mormando, register an unstinting stream of scepticism. The dispossessed local population was quite sure that all this was not for them. It was bread they wanted, not circuses. When the Fountain of the Four Rivers was unveiled on Piazza Navona in 1651, people complained: ‘Make these stones into bread!’ ‘We don’t want obelisks and fountains; it’s bread we want.’*

The curving paired colonnade extending in front of St Peter’s, cutting into what was the popular neighbourhood of the Borgo, was built by Bernini between 1657 and 1667 at a staggering cost of one million scudi, nearly half the total revenue the Church raised in a year. Criticism of the massive project came so early and so forcefully that the papacy was thrown into an unusual defensive position almost from the start. The first official announcement of the project insisted it was a form of poor relief, designed to create long-lasting jobs for the indigent Romans. (Mormando points out that only about 150 men were actually employed.) Bernini once wrote that the curving porticoes were the ‘maternally open arms’ of the Church, embracing ‘Catholics to confirm them in their faith, heretics to reunite them with the Church, and infidels to illuminate them into the true faith’. Mormando reminds us that this statement, so often thought key to the work’s meaning, came in a document that was a desperate attempt to defend the controversial project.

Bernini intended to close off the open side of the colonnade and introduce a third arm, never built, that would run right through the gap between the two curving elements. Rather than welcoming arms, the colonnade was a set of pincers, plucking visitors or pilgrims from the dirty streets of the Borgo, funnelling them into the corridor, then bringing them out at the other end and suddenly hitting them with the full sight of the round piazza and the basilica. The colonnade was both a barrier and a proscenium, turning the people of Rome into spectators and the Vatican into an image of itself. The grit of the Borgo was no longer to blow directly into the face of the Vatican. But the plan never quite worked. Goethe, contemptuous of the colonnade’s ‘alleys of marble that lead nowhere’, observed that the rabble was using them as public urinals: a fitting response, he thought, to Bernini’s classical posturing.

The people found other ways to mock Bernini. For the rest of his life he was dogged by allegations that his project at the crossing of St Peter’s, which involved carving out the great supporting piers in order to place four giant statues within them, had weakened the basilica and caused cracks in the cupola above. At the end of his life, he was absolved of any wrongdoing, and there has always been speculation that the charges were trumped up by his enemies. Everyone knew that incompetence resulting in damage to a sacred building carried serious penalties for an architect. Nonetheless, once people are yelling, ‘The cupola is falling down! The cupola is falling down!’ a line of tough questioning ensues, starting with: why has this man been allowed to hollow out the sturdy pillars of the church and fill them with gesturing statues?

A similar charge was made against the Four Rivers Fountain. Beyond complaints about pouring money into monuments while people starved, the rumour also spread that the hollowed-out rock beneath the obelisk would give way, causing the monument to crumble. The Bernini experts usually present this as fear-mongering among a credulous population. But with the ear attuned to the lethal ways of Baroque Rome, it starts to sound more like a verbal grenade expertly tossed under a monument that was already reviled as an unnecessary celebration of the papal family. When word spread that the obelisk might fall at any moment, taking the papal coat of arms with it, a counter-fantasy of dismantling took hold. After all Bernini’s achievement had been to give scope to the viewer’s desire for dramatic, imminent, frame-breaking movement.

Local voices occasionally argued against Bernini’s incursions in something like the language of anti-development protests today. An outcry met his and the pope’s plans to fill the tribune of Santa Maria Maggiore with two papal tombs, entailing the destruction of ancient mosaics in the church. Diplomatic accounts from the period report louder and louder opposition to Bernini, with the civic authorities denouncing him as ‘the one who instigates popes into useless expenditures in these calamitous times’. It’s unclear whether these protests would have succeeded on their own merits since the reigning pope Clement IX died before the project was very far advanced, and his successor, Clement X, much less interested in art, fired Bernini and commissioned a much more modest design.

Bernini lived long enough to watch his fortunes fade. In his last years he was not getting major commissions, the enmity of the population was near total, and his artistic standing and legacy were under threat. The year 1672 saw the publication of the Lives of the Artists by the most eminent authority on art at the time, Gian Pietro Bellori. Bellori was an idealist, and held Caravaggio responsible for dragging painting into the real world (‘Now began the representation of vile things, the search for filth and deformity’), but for Bernini he had only silence. He had announced that he was treating only artists who were no longer alive (a convenient ploy, perhaps), but his assessment of Bernini was clear: no sculpture in modern times matches that of the ancients, and no sculptor of the present day surpasses Michelangelo.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.