The Bauhaus stank of garlic. Alma Mahler, the wife of its founder and director Walter Gropius (and the ex-wife of Gustav), found the smell intolerable. She refused to eat the ‘obligatory diet of uncooked mush smothered’ in cloves of the supposedly purifying allium. The students and teachers who did eat it suffered bilious, flatulent attacks. After one meal, the painter and Bauhaus teacher Paul Klee, who prided himself on being a good cook, worried that ‘even his worms would leave him’.

The man responsible for the Bauhaus’s garlic problem was the Swiss expressionist painter Johannes Itten, a friend of Alma Mahler who had run a private art school in Vienna. Gropius, impressed with Itten’s unconventional methods, invited him to Weimar to teach the six-month preliminary course at the Bauhaus, a training in the principles of form and colour that all students had to take before they could learn a particular craft. Itten was a member of the cult of Mazdaznan, which fused Zoroastrianism with Christianity, and out of the first cohort of 120 Bauhauslers, as the pupils were known, about 20 were Austrian disciples of his. At the start of each class Itten made his students meditate and do breathing and ‘glandular’ exercises to help them unlock their creative potential, and encouraged them to follow his Spartan regimen, which included sleeping on straw pallets, fasting, bloodletting and colonic irrigation. He also persuaded the Bauhaus kitchen to serve only a Mazdaznan, garlic-heavy diet.

A photograph of Itten in the Barbican exhibition, Bauhaus: Art as Life (the largest and most comprehensive on the school to be shown in Britain since 1968, with exhibits previously hidden behind the Berlin Wall), shows him wearing a crimson robe of his own design. He has a shaved head like a monk, round gold-rimmed glasses and an intense stare. The only trained pedagogue at the Bauhaus, Itten had originally been a primary schoolteacher. He introduced some of the theories of Friedrich Froebel – the founder of the Kindergarten movement, who pioneered the use of educational toys – and encouraged his students to reconnect with their inner child. At the start of one term Itten told them that they would be making games for the next month, deliberately dispensing with the academic tradition of drawing from the nude or nature, so as to ‘lead all creative activity back to its roots in play’. His pupils learned to dissolve the world into patterns and forms, seeing everywhere Froebel’s Spielgabe: the pyramid, sphere and cube. Josef Hartwig created a chess set, still on sale today, with pieces solely composed of these shapes.

Itten’s motto was ‘Play becomes celebration; celebration becomes work; work becomes play.’ In this spirit Klee made hand puppets out of found materials such as beef bones and old electric plugs, some of them with physiognomies modelled on the Bauhaus staff. The Barbican curators, Catherine Ince and Lydia Yee, present the Bauhaus in part as an avant-garde playpen for adults. Parties, festivals and masked balls formed a large part of the curriculum, each marked by a frenzy of preparation. Gropius sought to encourage ‘friendly relations’ between students and teachers, who competed with one another to create the most outlandish, abstract costumes and decorations based on Bauhaus principles of geometry, space and colour. The nocturnal lantern processions and kite festivals they staged were representations, according to one observer, of ‘the joy of two hundred big and little children’.

Gropius, a 35-year-old architect and decorated officer just back from the front, founded the Bauhaus in 1919 by fusing two existing arts and crafts schools in Weimar. In a climate of postwar shortages and uncertainty, and against the background of the punitive Treaty of Versailles and the Spartacist uprising, he hoped to lay the cornerstone of a ‘Republic of the Spirit’. When we think of the Bauhaus not as an institution but as a style – the tubular furniture, sleek household appliances, lowercase fonts and glass-walled, flat-roofed buildings satirised in Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House – it is easy to forget Gropius’s original messianic ambition. His Bauhaus manifesto attracted the utopian and disaffected with its call for a unity between art and craft that would ‘rise one day towards heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystalline symbol of a new faith’.

Gropius sought to change the world by redesigning it, from the teaspoon to the skyscraper, according to the universal laws of form. On the cover of the Bauhaus’s first prospectus was an expressionist woodcut by Lyonel Feininger of the Cathedral of Socialism – the Bauhauslers affectionately referred to Gropius as Pius I. ‘Young people brimming over with new ideas and the desire to realise them … flocked to us from home and abroad,’ Gropius said in 1964, ‘not to design “correct” table lamps, but to participate in a community that wanted to create a new man in a new environment.’

For this purpose, Gropius gathered around him an amazing collection of avant-garde stars, mostly artists (‘We must not meddle with mediocrities,’ he said). As well as Feininger and Klee, he recruited Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Breuer, Herbert Bayer, Oskar Schlemmer, Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy. The Bauhaus was constructed like a medieval guild (the name deliberately echoed the word Bauhütte, a medieval masons’ lodge); teachers were addressed as ‘master’ rather than ‘professor’, and led the workshops alongside expert craftsmen; students were referred to as ‘apprentices’ or ‘journeymen’. The Barbican exhibition unsettles the myth of the Bauhaus as always cool, objective, abstract and rational, showing instead that the school began with a gothic, mystical self-image. The first logo, the winning entry in a student competition, was a mishmash of Eastern and occult symbols. Early pieces made in the workshops – bulbous earthenware pitchers by Otto Lindig, wooden reliefs by Joost Schmidt and stained glass by Josef Albers – were surprisingly heavy and expressionist. Sommerfeld Haus, one of Gropius’s private commissions, which became a testing ground for early Bauhaus techniques, was built using wood from a decommissioned warship and looked like an Alpine masonic lodge.

In 1922, Gropius and Itten came into conflict. According to the Bauhaus student Paul Citroën:

Itten had something demonic about him. As a master, he was either profoundly admired or, by his opponents (of whom there were many), equally profoundly hated. Whatever else, it was impossible to ignore him. For those of us within the Mazdaznan circle – a special community within the Bauhaus – Itten had a very special aura. You could almost call him a saint; his presence practically reduced us to whispers, and our respect for him was overwhelming. Should he treat us in a friendly and relaxed manner, we would be enraptured and inspired.

Itten’s followers, who dressed in identical monastic robes, went on three-week fasts, during which time they drank only hot fruit juice and retreated to the hills around Weimar to chant and puncture their skin with needles in detoxification rituals. Citroën made a sketch depicting the Mazdaznian cures Itten supervised; one crouched figure is shown giving himself an enema, another is vomiting, a third is wrapped in bandages after a bout of bloodletting. Gropius suspected that Itten, having indoctrinated the majority of students, had ambitions to take over the school. Gropius was under pressure too from the increasingly right-wing Thuringian state government, which funded the Bauhaus and worried it was becoming the centre for a religious cult; they wanted it to prove its worth and contribute to its costs by collaborating with industry. Itten, who did not have to deal with local politics, thought that to do so would be to sell out. Unless they did, Gropius argued, the future of the Bauhaus looked bleak. In April 1923, Itten resigned, and Albers and Moholy-Nagy took over the preliminary course, which they purged of meditation and ritual. Extended to a full year, it would become the basis of art and design education all over the world.

Gropius hoped the school would find renewed purpose in the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition, which would display – under Gropius’s new slogan, ‘Art and Technology: A New Unity’ – how the student workshops could become ‘laboratories for industry’. The Bauhaus would infiltrate the factory, introducing its romantic ideas to the machine age, bringing the qualities of the handmade to industrial production. ‘The artist possesses the ability to breathe soul into the lifeless product of the machine,’ Gropius told his students, inviting them to fetishise commodities, ‘and his creative powers continue to live within it as a living ferment.’

With this move, the Bauhaus as we know it was born. The shift in emphasis was controversial among the artists who remained; like Itten, they felt art was being sacrificed to economics. ‘We now have to aim at earnings – at sales and mass production!’ Feininger complained in a letter to his wife. ‘But that’s anathema to all of us and a serious obstacle to the development process.’ Although it had dropped chanting and garlic eating, the school continued to produce glittery-eyed apostles. The Bauhaus community became, as Schlemmer wrote, ‘pioneers of simplicity’, creating designs ‘for all of life’s necessities which at the same time are respectable and genuine’.

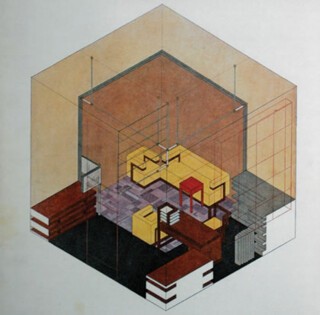

The 1923 exhibition centred on the Haus am Horn (known as the Experimental House), a modernist dwelling designed by the painter Georg Muche that was intended as a showcase for the Bauhaus idea of economical and functional living. It was a white, flat-roofed cube, with small rooms arranged around a central clerestory-lit living area, and was decorated entirely with furniture and fittings made in the workshops – Carl Jucker’s telescoping wall lamps and Breuer’s slat furniture. One critic compared it to a ‘North Pole Station’ and many visitors found the sparsely furnished, pictureless rooms cold and industrial: ‘Tall standard lamps of iron and glass tubes, severe, undimmed by silk shade, recall physics instruments; seats look like looms, furniture recalls printing presses, teapots, water gauges.’

However, the Weimar government was not appeased by Gropius’s efforts and the Bauhaus was dogged by funding cuts and negative articles in the press. Weimar, one Bauhausler wrote, was as ‘an eyrie of vultures who constantly strike at us’. Gropius started an appeal, inviting Friends of the Bauhaus, including Albert Einstein, to provide ‘unanimous moral and material support’ in the face of ‘the attacks that are jeopardising its peaceful work’. On Gropius’s birthday in 1924 the students gave him a makeshift cannon to help in his efforts at defending the school. After the nationalists gained power that year, police searched the campus and Gropius’s own house looking for communist literature. When the local government insisted on the right to vet new staff, Gropius and his masters and apprentices agreed to close the school down.

The liberal mayor of Dessau, Fritz Hesse, invited Gropius to move the Bauhaus to his booming industrial city, home to the Junkers aircraft factory, offering to pay for a new campus. In Dessau the wild utopian focus of the early days was reined in further, as the school’s workshops were geared for the practicalities of mass production. A company was founded, Bauhaus GmbH, to sell its products. These included Breuer’s famous tubular steel furniture, made in collaboration with local aeronautical engineers, and books with dynamic typography designed by Herbert Bayer and Moholy-Nagy. However, none of these had any commercial success: the biggest seller proved to be the wallpaper designed in Hinnerk Scheper’s mural painting workshop.

Gropius designed a building on a site two kilometres from the city centre, a factory-like series of asymmetrically arranged white cubes with trademark flat roofs, which would become a much visited emblem of the International style. The new three-storey studio block had a huge glass wall – it was nicknamed the ‘aquarium’ – through which you could see the students at work. The school was an incubator for the new, modern individuals Gropius hoped to create; the theatre, directed by Schlemmer, was at the heart of the building, where it could be opened up to both the canteen and the auditorium. Connected to the main building by a bridge was a five-storey building, known as the Prellerhaus, which had 28 live-work studios for junior teachers and students, with generous south-facing balconies and tubular-steel railings. Gropius also built modernist villas in a nearby pine forest for himself and other senior masters. Everything – even the laundry chutes and the dustbins – was conspicuously modern and ingeniously designed.

Wandering around the Barbican exhibition, admiring the crisp, clean products on display, the tea sets and the table lamps, I couldn’t help wondering if a Bauhaus education would have made me a better person: uncluttered, disciplined, ordered. Would living in this community of aesthetes have been inspiring – or insufferable? The brochures that advertised the Bauhaus – ‘Are you looking for a stepping stone to the new times? Are you looking for the place of determined experimentation?’ – show that the school was populated by a reassuringly dishevelled crowd. T. Lux Feininger, the 16-year-old son of the artist and, along with Felix Klee, one of the youngest students at the Bauhaus, captured daily life there in his many photos of the school. There is a wonderful picture of the 23-year-old Breuer, who headed the furniture workshop, with his ‘harem’, a police line-up of three female students with backcombed hair. Parties were propelled by the music of the Bauhaus jazz band; at the Metal Ball, guests in bizarre, glittering costumes hurtled down a long slide into a foil-lined room decorated with reflective balls; in Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, students danced around the Bauhaus buildings in burlesque, puppet-like outfits that were designed to restrict their movement and inspire new forms of bodily expression. The Barbican exhibition, in devoting so much space to such revelry, successfully captures both the Bauhaus’s anality and its exuberance.

In 1928, Gropius resigned as director, claiming he wanted to concentrate on his private architectural work. He thought that the renewed attacks against the Bauhaus were directed at him personally, and complained that 90 per cent of his time was spent defending the school from hostile criticism. Moholy-Nagy, Breuer and Bayer followed him in setting up on their own, and Hannes Meyer, a self-professed ‘scientific Marxist’, who had joined the faculty the year before to run the newly established architecture workshop, took over the running of the school. He was a committed functionalist, and under his leadership the institution became more of a trade school. ‘It had a different soul,’ Nikolaus Pevsner said of Meyer’s impact. ‘In came a severer geometry.’

In 1930, Fritz Hesse dismissed Meyer because of his uncompromising communism. With the onset of the Great Depression and the rise of the Nazis, the school appeared an unaffordable luxury. On Gropius’s recommendation, Meyer was replaced by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, known for his Barcelona Pavilion and luxurious private houses. A crowd of students, many of them communists scandalised by Meyer’s dismissal, gathered in the canteen and accused Mies of elitism, demanding he stage an exhibition of his work so that they could decide if he was fit to be the new director. Mies called in the police and had the canteen cleared; the school was temporarily closed and several students expelled. Before the start of the 1931 academic year, in an attempt to prevent further disruption, students were presented with an infantilising contract they had to sign before they could enrol: ‘With my signature I undertake to attend the courses regularly, to sit in the canteen no longer than the meal lasts, not to stay in the canteen in the evening, to avoid political discussions, and to take care not to make any noise in the town and to go out well dressed.’

Mies once described himself as the ‘clean-up woman’ of the Bauhaus. He commuted from Berlin three times a week to preside over its end. In August 1932, despite Mies’s apolitical stance, the Nazis, who had recently come to power in Dessau, closed the school. Iwao Yamawaki, one of its Japanese pupils, created a photo-collage, The Attack on the Bauhaus, depicting Nazi officials marching down the façade of Gropius’s flattened building. An editorial in the fascist Anhalter Tageszeitung gloated that its closure represented ‘the disappearance from German soil of one of the most prominent places of Jewish-Marxist “art” manifestation’. They called for the school’s demolition, but the building, to them a symbol of degenerate primitivism, was too valuable a piece of real estate and became a Nazi training ground. Pitched roofs were added to the masters’ villas, turning them into more traditional German suburban homes.

Mies moved the Bauhaus to Berlin and rented an abandoned telephone factory, which the students helped transform. However, the Bauhaus was still deemed a hotbed of ‘cultural bolshevism’, and on 11 April 1933, a few months after Hitler became chancellor, fascists surrounded the building. ‘Early in the morning the police came in trucks and closed down the Bauhaus,’ one student recalled. ‘Those Bauhaus students who did not possess suitable identification papers (and who had, in those days!) were taken away on the trucks.’ Mies campaigned valiantly to be allowed to reopen the school – he noted dryly that the narrow benches in the Gestapo headquarters he visited every other day for that purpose were of terrible design – but in July 1933, after 14 years of existence, faculty and students agreed to disband the school.

The Barbican exhibition ends here, having given a rare insight into the workings of a school too often overshadowed by its legacy. The diaspora spread the school’s modernist ideology around the globe (the curators resist the temptation to show how the émigrés left their mark on Britain). Many of the Bauhaus’s teachers emigrated to the US: Gropius and Breuer to the Harvard School of Design after a brief stint in London; Albers to Black Mountain College and Mies to the Institute of Technology in Chicago. In 1937, also in Chicago, Moholy-Nagy founded an influential school of design known as the New Bauhaus. There they built a new, purist world of steel and glass, adapting their socialist views to corporate America, grateful for a second chance. Some, such as the Bauhausler Franz Ehrlich, weren’t so lucky. The communist architect, who had worked in Gropius’s Berlin office, ended up in Buchenwald, where he was put to work designing prison blocks, a guesthouse for Hermann Goering, an army barracks, a weapons factory, and a zoological garden and casino for the SS. In a final indignity, with the school’s utopian rationalism taking a dystopian turn, he used Bauhaus sans-serif lettering for the camp’s iron gates.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.