It’s impossible to overstate the extent to which the game of baseball is integrated with American life in general, and its literary scene in particular. The sport’s popularity has wavered – it has occasionally been eclipsed, in market share, by American football and basketball – but its importance as a cultural signifier has never faded. To the mathematically minded, it is a game of statistics; to the outdoorsman, it is pastoral. The gossip sees it as a pageant of personalities, the intellectual uses it to establish working-class cred and the working man philosophises over it. There must be very few American boys who haven’t played it, and even fewer American humans who haven’t seen it on TV. It has produced countless idioms and metaphors: home run, bottom of the ninth, bases loaded, strikeout, pinch-hitter, double-header, major league, minor league, bullpen, slugger. There are people who use these terms, utterly confident in their meaning, who couldn’t name a single active player. Baseball is big in America, but the idea of baseball is even bigger.

American novelists have a particularly complicated relationship with the game. Perhaps it’s because baseball and novel-writing are so similar: both take a long time, and consist mostly of silent contemplation interrupted by occasional brief bursts of intense activity. They’re both rather boring to watch. And everybody thinks they could do both, given half a chance. Of course, everybody is wrong. Playing baseball is hard, writing a novel is hard, and you might think that writing a novel about baseball would be the hardest task of all. That hasn’t stopped large numbers of American writers producing baseball novels. A few have achieved the status of bona fide classics: W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe, Robert Coover’s The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., Philip Roth’s The Great American Novel and Bernard Malamud’s The Natural.

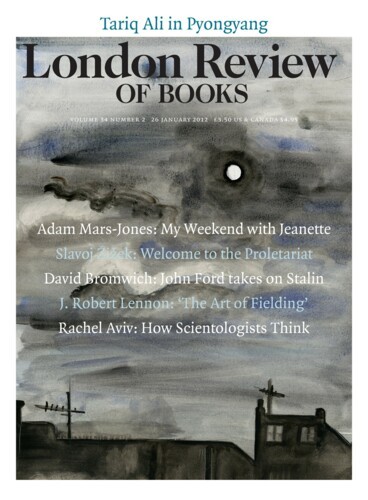

It was the last two of those novels I kept thinking of as I read Chad Harbach’s highly entertaining, intermittently excellent, unapologetically masculine The Art of Fielding, a telephone directory of a novel about scrappy underdogs trying to win it all. The book is a throwback to a bygone, if not universally mourned era when charismatic white male novelists wrote intelligent bestsellers, and one senses that it is intentionally so, much in the way the literary journal Harbach cofounded, n+1, is a self-described throwback to the heydays of Lingua Franca and the Partisan Review. It is a work of stridently unexperimental psychological realism, featuring likeable characters with cute nicknames, dramatic events that change people’s lives, easily identified and fully consummated narrative arcs, transparently conversational prose and big, obvious metaphors. The Art of Fielding is also a campus novel, that other great American (and British) literary vessel whose time has come and gone. Indeed, the book’s longing to revive these admittedly useful but unavoidably creaky standbys of literary form is so ludicrously foregrounded that the critical reader may perceive it as a kind of threat: a cuff on the shoulder, a meaty finger to the chest. Are ya in, the novel seems to be asking in its opening pages, or are ya out?

It’s very hard not to be in. Harbach is a solid writer, inoffensively funny, pretty good at character, a prodigy at suspense. The book’s great success, though, is its charm: its eagerness to please, its casual, wholesome seductiveness. Despite predictability in the plot and lapses in the writing, it’s the charm that keeps one going. Who the hell bothers to be charming anymore? Chad Harbach, that’s who.

Henry Skrimshander, ace shortstop, is a working-class boy from South Dakota who is studying at Westish College, a quaint sub-Ivy League place ‘in the crook of the baseball glove that is Wisconsin’. He owns only one book: The Art of Fielding, a philosophical sports instruction manual by a legendary (and fictional) shortstop for the St Louis Cardinals called Aparicio Rodriguez. Henry is a virgin, a rube and skinny as a broom handle. He has been recruited by the hulking Mike Schwartz, team captain, catcher and taskmaster of the Westish Harpooners – so named because of a rather tenuous connection to Herman Melville, the subject of a legendary dissertation-turned-critical-blockbuster called The Sperm-Squeezers by the college president, Guert Affenlight, the only thing of worth he’s ever produced. Guert has a daughter, Pella, 23: plucky, comely and on the run from a bad marriage. He also harbours an advanced crush on Henry’s roommate, Owen ‘Buddha’ Dunne, voracious reader and second-string Harpooner. The book’s opening chapters introduce each of these characters, moving among them in a roving, jovial third-person limited, presenting their quirks and habits of thought. They’re easy to like – innocent Henry, fierce Mike, bemused Guert, self-deprecating Pella. Only studious Owen fails to earn his own point of view: instead, he is the novel’s fulcrum, its dramatic centre of gravity.

The drama begins when Owen, idling in the dugout during a Harpooners game, distracted by a book, is knocked out cold by a wild throw to first base – Henry’s throw, the first error of his college career. This event sets various plotlines into motion: Guert, first on the scene and first to the hospital, finds his crush blossoming into illicit love, which Owen will eventually come to reciprocate. Henry, who believed his talent for fielding was flawless, experiences the first signs of doubt; as his performances worsen, and his doubt deepens, his champion, Mike, begins to question his own judgment and his own life choices. This complicates Mike’s nascent romance with Pella, and his command of the team. Things go from bad to worse for everyone: Guert ignores his doctor’s warnings and begins to get chest pains, Pella’s husband shows up to confront her, Mike’s joints turn to mush and Henry seems to be losing his mind. Lovers betray each other and say hurtful things.

And yet somehow, of course, the team copes with it all, wins the league championship and reaches the nationals. The players grow beards. One character stops eating, another punches a tree. There’s a near drowning and a valuable earring is swallowed. The novel culminates in a series of overly convenient, implausible and heavily symbolic climaxes: a carefully worded threat, a macabre graveyard ritual and the inevitable great question: will the Harpooners win the Big Game? (To Harbach’s credit, the answer isn’t terribly important – but it’s a shame the question had to be asked at all.) When the dust settles, our players are allowed new beginnings: Harbach dutifully winds them up and points them towards the sunset. And the book ends where it started, with Henry Skrimshander dropping into his crouch, waiting for the next ground ball.

All this is presented in prose that is, if unadventurous, at least shapely. Harbach is good at social nuance and has a feel for the physicality of a scene. Here’s Guert Affenlight, infatuated with Owen, sitting in the bleachers to watch a few innings of play: ‘His elbows rested on his knees, his long knobby fingers interlocked. His forearms, hands and thighs formed a diamond-shaped pond into which his tie dropped like an ice fisher’s line.’ Or Pella’s first glimpse of the temperamental Chef Spirodocus, her future employer: ‘A small but substantial man, built low to the ground like an Indian burial mound, was scraping mashed potatoes into a giant baggie.’ The dialogue is spotty: too often characters merely speak the words that must be spoken for the plot to move forward. Rifts between characters are usually established through arguments in which what is said is precisely what is meant. Sometimes, though, Harbach offers a nice comic surprise, as when Owen introduces himself to a bewildered Henry: ‘My name’s Owen Dunne. I’ll be your gay mulatto roommate.’ And then there’s my favourite exchange in the novel, when Mike, asking Pella out on a date as though she’s just another Westish student, gets a frantically sarcastic reply:

‘Free? Heavens, no. After a capella practice I’ll be volunteering down at the soup kitchen while I finish my paper on the theme of revenge in Hamlet. Then my sorority has a mixer with the Alpha Beta Omegas, my bulimia support group is getting together for dessert, and after that I have a date with the captain of the football team.’

‘I’m the captain of the football team.’

There was a long pause.

‘Oh. Well, in that case. What time can you pick me up?’

These characters find questions of identity puzzling and amusing: race, religion and sexual orientation are opportunities for quiet gags and rarely intrude on the action of the plot. One senses that for Harbach this is a fantasy world which he wants to populate with fantasy people, people for whom class and colour are mere curiosities, obsolescent quirks. He doesn’t want these things to get in the way of the story. ‘Country music’s gay,’ says Izzy Avila, Henry’s own protégé at shortstop; ‘Owen cleared his throat.’ A sheepish apology is all that’s needed. Izzy himself is Latino, but only in the vaguest way: he likes Spanish hip-hop, calls things ‘estúpido’. His ethnicity is adornment. In a way this is part of the novel’s charm: it is as ambivalent about its own identity as its characters are about theirs. Every time an artefact of the early 21st century appears, you get a jolt: you can’t believe that this quaint universe of team spirit, funny town names (Opentoe, Illinois) and robust male friendship actually contains iPhones and internet porn, let alone race and class-based conflict.

Again and again, Harbach pulls his punches. When Guert at last comprehends that Owen is, in fact, black, he reacts not with the existential horror that might have dragged the story into more dangerous territory, but with temporary bemusement. When Owen emerges back into consciousness after his injury and says he’s ‘having some trouble remembering things’, we brace ourselves for his slide into insensibility and death. But his symptoms sort of go away, and by the novel’s end he’s smacking singles into centrefield. Pella, the book’s only female voice, exists solely to be slept with or not slept with, to be married to or not married to, to be her father’s daughter or be independent. She is clever and self-deprecating, as all young women in novels must now be, but she has none of the drive or the strangeness of the men, whom she spends most of the time taking care of. You wait for her rebellion, for her rejection of these habits of being, but it never comes.

But unlike most novels of middle-class self-actualisation, The Art of Fielding knows that’s what it is, and seems to be making an argument about its own existence: I am enough. I don’t have to be more. There’s a telling riff in Chapter 50 about baseball’s supposed ‘postmodern era’: in 1973, Pittsburgh’s Steve Blass, after the death of his teammate Roberto Clemente, lost his mojo and became the first baseball player to be ruined by overthinking. This, we are told, is Henry’s problem: self-awareness. Guert, a literary critic, finds the hypothesis rather wonky, but holds his tongue: ‘Literature could turn you into an asshole,’ he reflects. ‘It could teach you to treat real people the way you did characters, as instruments of your own intellectual pleasure.’

‘Theory is dead,’ the editors of n+1 wrote in their 2005 manifesto, ‘and long live theory. The designated mourners have tenure, anyway, so they’ll be around a bit. As for the rest of us, an opening has emerged, in the novel and in intellect. What to do with it?’ It is tempting to imagine that this novel is Harbach’s answer. You can still write a baseball novel, he seems to be saying. You can write a campus novel. You can write a novel in which all the plotlines are wrapped up and almost everything turns out almost all right. You can write a novel that doesn’t want or need to be analysed, about which it’s fine just to say: ‘I liked it. It was good.’

But it could have been better. It could have given the designated mourners, tenured or not, a little more to chew on. It could have done something unexpected, something uncanny. It could have risked making its readers angry. Instead, Harbach is too much like the Henry of Chapter 1, ‘bland, almost bored, like … a virtuoso practising scales’. Will Harbach, like Henry, lose his mojo? Will he be forced to reinvent himself? Will he dare to turn off the charm and show us what else he’s got?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.