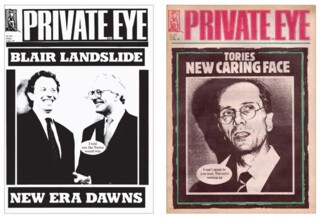

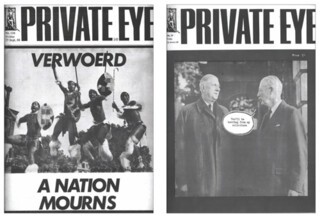

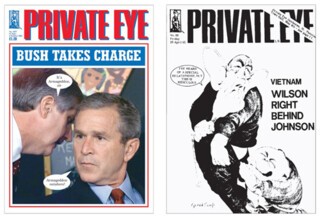

The main feature of Private Eye: The First Fifty Years, at the V&A until 8 January, is a large wall plastered with the magazine’s covers. A monumental celebration, on a grand scale, of a scruffy little rag whose production values, to this day, owe much to its memorable antecedent, the British Railways lavatory roll. It’s a good thing that only one of them has lived to tell the tale. And a pleasure to see the Eye crowing over its longevity and many narrow escapes – several fools and villains have tried to kick it off the dung-heap and wring its neck. But, as the covers on this wall of fame remind us, fools and villains are the lifeblood of the paper. Every reader has a cherished bubble photo, from Wilson and Biafra through Kissinger in South Africa (HK to Vorster: ‘I’m only here for De Beers’) via James Goldsmith, Robert Maxwell, Rupert Murdoch, to Mugabe, Bush and Blair. For fans of a pensionable age, Verwoerd’s assassination (‘A Nation Mourns’, 17 September 1966) is a star cover. Younger readers may prefer a ghoulish photo of Norman Tebbit, the Tories’ ‘New Caring Face’ in 1986, and his prince-of-darkness bubble: ‘I can’t speak to you now. The sun’s coming up.’ But if a long-lost favourite is not on view at the exhibition, it can be found again on the Eye’s website, in the covers library.

The rest of the show is an assortment of drawings, cartoons and memorabilia, crammed into a pair of rooms off the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation gallery, where Eye aficionados must make their way past 1700 years’ worth of magnificent Buddhist sculpture, before they enter the profane world of the magazine. The current Eye editor, Ian Hislop, has a passing resemblance to a small eastern deity, but even so it’s something of a lurch from this hall full of serene statuary, including the head of a 13th-century Buddha carved from sandstone, to a Scarfe cartoon of Harold Wilson with his lolling tongue in close proximity to Lyndon Johnson’s bottom (‘Vietnam: Wilson right behind Johnson’, 30 April 1965). ‘I’ve heard of a special relationship,’ the president muses, hitching up his trousers, ‘but this is ridiculous.’ Somehow the exquisite bodhisattvas watching you on your way through reinforce the point the Eye was always keen to make, that post-imperial Britain is a sorry spectacle.

Other cartoons on show, mostly familiar, come from dozens of the Eye’s contributors, including the superb Ed McLaghlan, Michael Heath (Great Bores of Today etc), Ken Pyne, whose National Association of Builders Convention (1986) is proudly displayed (as are the many builders’ cracks in the drawing), Barry Fantoni, Nick Newman, Martin Honeysett, Willie Rushton … the list is long. Most of this, including the strips, is topical, socio-comic work, or lunatic observational – the country seen from another planet – or simply anarchic. Scarfe and Steadman, the two high executioners, were up for darker kinds of commission, though they weren’t seen in the magazine much beyond the 1970s. Richard Ingrams, the editor for more than 25 years, used to work up subjects with them in the old days until, as he recalls it, Scarfe ‘got very grand and didn’t like being given ideas’. Despite the odd little text or a letter in longhand, writing is in short supply here. An intriguing re-creation of the editor’s desk – known in the Ingrams period as ‘the Bermuda Triangle’, where items of importance had a habit of vanishing – stands by the exit. But The First Fifty Years fails to commemorate the many columns and files of investigative journalism that the Eye has churned out over the years: this is first and last a show about the images that have won it so much popularity.

The loss is made up for in an anniversary book of the same title, an A-Z of the paper’s triumphs and defeats, its luminaries and hangers-on, its enemies and bêtes noires (Private Eye, £25). The in-house author Adam Macqueen recycles many of the good old stories and tells us much about the comings and goings at the magazine. The book is good on editorial tiffs. How Christopher Booker, the original editor, was fired while on holiday in 1963; how he went on, in 1976, to lay into the Eye just as Goldsmith, who had issued 63 writs against the magazine and its distributors and sought to bring a private suit for criminal libel, appeared to have it on the ropes; how John Wells felt that his jokes were ‘ostentatiously removed, spat on and ground into the carpet’ after brainstorming sessions with the others; how, as time went on, Ingrams loved to wind up his colleagues in the office, push his chair back and look on at the results, muttering with immense satisfaction: ‘Not a happy ship.’ Goldsmith settled out of court for £30,000 (Eye readers had contributed £40,000 to the defence fund). But the case had taken its toll on Ingrams, even if he hung on in a state of strange distraction for another ten years.

Goldsmith convinced himself that the Eye had ‘revolutionary views’. It was part of a conspiracy, he believed, to feed the nation ‘pus’ and ‘destroy our society’. Paul Foot, who’d left the magazine a few years earlier to write for Socialist Worker, had indeed edged his way back to Greek Street at the time of the case, to do odds and ends for Ingrams. International socialism notwithstanding, Goldsmith was wide of the mark. Private Eye understood from the outset that the really destructive force to watch was Rupert Murdoch, with his radical four-point programme for the UK: take the British punter by the heels, shake him about a bit, offer him the breast (page three), then train him for the potty, where a lifetime’s gratification was assured so long as he stayed put and strained manfully to pop a regular result into the News International coffers. That agenda, by and large, has been achieved and the Eye has followed the story well beyond p. 94 to the phone hacking scandal. An embattled, wrinkly Murdoch ‘answers critics’ on a February cover with the bubble: ‘I overhear what you’re saying.’

Lord Gnome’s organ hasn’t always performed to order. The paper was a near disaster within two years of starting up, until it was rescued by Peter Cook – the founder of the Gnome dynasty – on his return from the US tour of Beyond the Fringe. At the end of the 1970s, the Eye stumbled into a period of pointless malice and political irrelevance: Julian Barnes saw how bad things threatened to become when he reviewed Patrick Marnham’s book about the magazine – a kind of ‘Private Eye at 21’ – in the LRB in 1982 (‘the radical lampoon has become required reading on the magazine syllabus of every Sloane Ranger’). Four years later, Ingrams resigned and the little buddha from The Mumbles took charge. Public school and churchy – just like Ingrams – Hislop is a chip off the old block. Like Ingrams and Booker, he is cross, even though you can’t always tell. But he has understood far better than either of his predecessors how to keep standards commendably low while aiming rigorously high. A lot of the nonsense and egotism in the office has been swept away, if Macqueen is telling the truth; the tone of the magazine is less rebarbative and the jokes are just as good. The paper is a great deal sharper than it was in the doldrum years, when Foot had absconded for a second time – to the Mirror – and Ingrams was learning to accept that he’d lost his taste for a fight.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.