Everything is changed at Dulwich Picture Gallery by the fact of Cy Twombly’s death. He died in Rome, aged 83, on 5 July, just a week after the current show at Dulwich opened (it closes on 25 September). Twombly and Poussin: Arcadian Painters is the exhibition’s title; it brings together a range of works roughly deriving from the artists’ shared feeling for poetry and mythology, Italian landscape, the life of the senses, the cult of Pan; and inevitably the mind now turns to the enigmatic tag so important to Poussin, ‘Et in Arcadia ego’, meaning (art historians cut their teeth on this) that death is always present in the land of milk and honey, or maybe, imagined as spoken inconsolably by a body inside the tomb, ‘I too – not death in the abstract but this warm hand – once touched spring water and the yielding earth.’ The urgent, despondent first version of this theme by Poussin is hung in the show’s room one, lent from Chatsworth. It sulks under discoloured varnish, but its theatrics – the naive scholarliness of the shepherd tracing the inscription – are irresistible. Death is displaced in the painting to a figure in the foreground whom at first we barely notice: a typical Poussin figure, half-asleep on the ground, white-haired and a little overweight: as if death, if we’re lucky, will be a long weary half-consciousness of water still flowing (the figure is a river god holding a jar whose contents spill through his fingers) and a shelf of grass.

Death is everywhere at Dulwich. The gallery is showing a short film by Tacita Dean of Twombly a year or so ago, puffy and slow and sly, fumbling round his studio in Virginia. The film moves (rather in the same way as Dean’s tremendous portrait of old Michael Hamburger fondling his apples) from a world of light and vitality, glimpsed through the studio blinds, towards a final montage of grey trees against a storm-warning sky. Halfway through the exhibition one turns off into Soane’s strange shrunken mausoleum for the gallery’s founders, and in the half-light among the sarcophagi is a Twombly sculpture: a black rose resting on a marble pebble resting on a box covered in faded velvet. The label on the box reads: THAT WHICH I SHOULD HAVE DONE, I DID NOT DO. Nicholas Cullinan, whose great idea this exhibition was, makes the connection to Poussin’s contrary (though not, as I hear it, self-vaunting) ‘Je n’ai rien négligé.’ But the rose on the unlovely pebble also reminds me of Poussin’s habit of bringing back bits of wood, stones, moss, lumps of earth from his rambles by the Tiber; and the story of him reaching down among the ruins for a handful of marble and porphyry chips and saying to a tourist: ‘Here’s ancient Rome.’ Both artists are humorists as well as death-haunted. (Richard Wollheim once said to me, apropos The Triumph of Pan, which is in the exhibition, that he did not feel Poussin ever managed the difficult business of laughter in paint. Maybe not: but he was good at showing human beings trying to be funny. He was interested in the proximity of a laugh to a rictus.) ‘Witty and funereal’ was how Frank O’Hara described Twombly’s sculptures early on.

Across from the main exhibition is a room given over for the next two months to the Duke of Rutland’s five paintings, done by Poussin for Cassiano dal Pozzo, of Ordination, Confirmation, Marriage, Extreme Unction and the Eucharist. ExtremeUnction is a heart-wringing picture, and in the circumstances one gravitates towards it. Never has the green of the dying man’s bedclothes – like shot silk, like a snake’s skin, like a putrefying body – seemed so horrible and beautiful. But one looks at the painting with Twombly’s and Poussin’s conception of death and life in mind, so just as important as the horror is the power of life continuing. People have always been attracted, almost guiltily, to the show-stopping grace and carelessness of the serving woman over to the right in Extreme Unction, cribbed from a sarcophagus, waltzing through a doorway on her way to the kitchen. ‘Et in morte ego,’ she might be saying. I have a job to do. And out past an opening behind the dying man’s head is a grey and silver abstract arcade – death as emptiness, measured recession from the world, light-filled eternity. Twombly (Cullinan is excellent on this in the catalogue) has a collage where he pastes a reproduction of one of Poussin’s drawings for Extreme Unction next to a flurry of dirty oil and chalk.* But the Poussin is cropped: the corpse and the moment of salvation are nowhere to be seen, and what registers is a grim processional of figures wringing their hands. One sees why Twombly has written over it the word ‘Bacchanalia’. Poussin’s Triumph of Pan, reversing the thought (perhaps this is what Wollheim meant), is transparently a Triumph of Death. But this is the reason – this is what the whole concatenation of works and circumstances at Dulwich brings home – for the peculiar human thing called comedy.

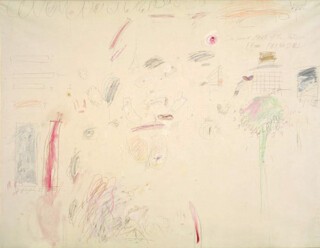

I have to confess that Twombly’s comedy has most often in the past left me cold. (It seems awkward to say this, but the high pathos and irreverence of his life’s work seems to leave no room for obituary flannel.) I know the paintings by him at Dulwich that strike me as successes, and they are rather few. Primavera is one, especially extracted from its slightly overbearing series. Its combination of savage stroke-play and fruit-juice colour hits home. The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus is another. Aesthetic intensity in Twombly, to state the obvious, is bound up with haphazardness – the search for a moment at which the mind’s faltering, inattentiveness and whimsicality happen on a new order of things. One that escapes, so the painter hopes, from the normal post-Miró play of deskilling and encounters the silliness of the world. Of the world, not of painting. This seems to me Twombly’s vision of Arcadia: a condition very close to acedia, granted, but where the scruffiness and inconsequentiality of the mark-making seems to hum with the laziness of art, as opposed to the aleatory or the uncentred or the il n’y a pas de hors-texte – or any such big idea. Modesty like this is difficult: too much of the time in Twombly the big ideas – as stale as they are impeccable – seem to me in charge.

My test of true, generative haphazardness, here as elsewhere, is whether the picture’s handwriting does anything to the normal art-ness of picture space: to the kind of entry into an alternative world the picture offers, and the intimation of that world’s shape, proximity and being-apart-from-us. Normal modern-art-space is unbounded and ungrounded, and once upon a time those qualities may have had some life – some danger – in them. Not any more: the shallows have become a paddling pool. It is as if viewers now go to visual art for reassurance about the endlessness (the harmlessness) of the ‘virtual’, as once they went to it for a model of totality. The best I can do here is invite the visitor to Dulwich to look at Herodiad (1960) and compare it to Return from Parnassus (1961). I see winsome infinity in the former: perfectly genial, yet for me having nothing to do with the hard deathliness of its Mallarmé source. In Parnassus, by contrast, a true closeness and matter-of-factness of everything, nudging and spoiling the picture plane, do register, I feel, as the proximity – the embarrassment – of bodies. This is one of the few Twomblies where, for me, the sticky-sweet eroticism, all little cocks and bums and glops of semen, ends up driving the language towards a new apprehension of the scene. (Return from Parnassus, by the way, stems from a 17th-century mock-classical poem – Twombly was a great reader – about lads reeling home from a night on the town.)

Haphazardness in Twombly goes along with writing. He has had many literary admirers. His script can be magical: brilliant loopiness modulating into Alzheimerish scrawl. Writing was his way of getting poetry into pictures, which he very much wanted to do – especially poetry filled with elegiac regret. There is a stunning set of quotations from George Seferis (probably a bit garbled) running down the right-hand side of Estate in the show’s last room, copied from Three Secret Poems: ‘Our snow white youth/that is infinite, and yet so brief’. And up above, repeated: ‘say goodbye Catullus to the shores of Asia Minor.’ I think (it’s hard to be sure) that two lines lower down read ‘forever exhausted/forever loving’, though the final word is almost indecipherable, as if overtaken by the exhaustion. All this is a clue to the meaning – the intentionality – of Twombly’s writing, which is always pretending, often irresistibly, to be palsied or childish. The loving and the barely readable seem to go together for him, as well as the loving and the terminally tired. Right at the bottom in Estate the writing gets larger and larger, more and more five-year-old; the final ‘forever’ is enormous, plangent, long drawn out, like a parody of Mahler’s ‘Ewig’ at the end of Das Lied von der Erde. A loving parody, of course.

I greatly admire Twombly’s Arcadian mood: by which I mean his wish to expose himself to the world as it happens, as it impinges on the passive senses. This is modernity’s only utopia. But it is horribly hard to get to – to get back to. All that careful cultivation of negative capability – all Rimbaud’s ‘systematic derangement of the senses’, or Twombly’s systematic dispersal – can so easily turn out to be cultivation, only more so. Poussin, next to Twombly, seems an utter naif. Every painting of his, however learned and overplotted, has a moment in which the world intercepts him and sets him painting for dear life. The sole of the river god’s foot in Arcadia; the crumbling riverbank in The Nurture of Jupiter, and the drowned-white reflection of a cherub’s knee; the astonishing crevices and imperfections in The Triumph of David’s paving (floors in Poussin!); the mud on ARoman Road … But the episodes are ubiquitous. Put a foot in a pair of sandals, just once in the too Parnassian crowd on Apollo and the Muses on Parnassus, and Poussin cannot help himself getting sidetracked by the pressure of a set of toes. The sidetrack is the road. I know that Twombly would have given his eye teeth to have the world crop up in his painting as it does all the time in Poussin. But no artist was more aware of – more honest about – his belatedness. Tacita Dean has this right. Say goodbye, Catullus.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.