One of Ed Miliband’s first decisive acts on becoming Labour leader (one of his few decisive acts, sceptics would say) was to appoint as his press secretary a seasoned hack with no illusions about how the media work. He chose Tom Baldwin of the Times, by all accounts about as unillusioned as they get. I assume the point of hiring Baldwin was to have a News International insider who could mix it with the likes of Andy Coulson, although that’s an idea Miliband is doing his best to bury at the moment. At the same time, Miliband revealed his other side when he elevated his favourite maverick intellectual, the community organiser and social theorist Maurice Glasman, to the House of Lords. Glasman was under instructions to keep thinking outside the New Labour box. Baldwin and Glasman represent the yin and the yang of Project Edward Miliband: the bruiser and the dreamer. So far, though, there is little sign of harmony. One of Baldwin’s first acts was to issue an injunction to the broadcasters (who ignored it) and to Labour spokespersons (who didn’t) that it was time to stop talking about ‘the coalition’, as though the current administration were a consensual and collaborative enterprise. Its correct title, according to Baldwin, was ‘the Tory-led government’. Dutiful Labourites, with their eyes on the real enemy, started spouting this phrase. But not Glasman. The opening line of his fairly startling essay in this new collection of ‘Blue Labour’ thinking is as follows: ‘The Liberal-led coalition government, self-consciously progressive in orientation, while appropriating Labour’s language of mutual and co-operative practice, asks a fundamental question as to what distinctive gifts Labour could bring to this party.’

Not just a coalition, not just a coalition containing liberals, but ‘Liberal-led’? What’s going on here? The answer is that Glasman is simply doing what Baldwin was doing: identifying the real enemy. In many ways ‘Blue Labour’ is an unfortunate label, because neither Glasman nor most of the other contributors to this volume give much indication of sympathy for recognisable brands of conservatism. What they do show is a deep antipathy towards Liberalism. We are not talking here about Liberal Democrats, who barely merit a mention. The ‘Liberals’ Glasman has in his sights are not bound by party affiliation but by intellectual heritage and political instincts. They can be found in any party, including the Labour Party of Tony Blair and the Conservative Party of Blair’s heir, David Cameron. Glasman has no fundamental problem with Cameron’s notion of the Big Society, which he takes very seriously. He absolutely is not one of those who think it’s just a fluffy cover story for an ideological programme of radical Tory cuts (which is the way Baldwin would like to spin it). Glasman thinks the problem goes the other way. The Big Society is precisely what we need, but it’s been misappropriated by the people who champion it. It’s a good idea fallen among liberals.

So what’s the matter with liberalism? (I’ll drop the book’s capital L now.) As far as I can see there are two basic problems for Glasman, one related to what liberals never do and one to what they always do. The sin of omission is the inability of liberal politics to resist the depredations of international finance capitalism. This is the real passion that motivates Blue Labour: a sense that the country has been raped by the bankers, and all on the watch of a Labour government. They want someone, or something, to stand up to what the editors call in their introduction ‘the destructive, itinerant power of capital’, and they are acutely conscious that New Labour barely even put up a fight. That’s because liberals never put up a fight: all they do is talk about individuals, with their rights and responsibilities, their choices and their freedoms, without noticing that individuals are like confetti in the face of the whirlwind power of money. The Blair government was beholden to the City of London because it lacked the intellectual resources to organise any resistance, being convinced that big state socialism was dead, globalisation inevitable, and the job of politics to ensure that consumers had access to the best deals out there. Consumerism for Glasman is simply what liberalism looks like when it’s waving the white flag. What’s needed instead is the power of community-based organisation, because it’s only when individuals are joined together by something more substantial than the rights they share that they have any real say in the way the world treats them. Glasman is not fussy about what provides the glue: family, church, local pride, a sense of place, a sense of tradition (this, I guess, is the something ‘blue’ about Blue Labour). Anything will do so long as it makes community life sticky enough to trap the forces of globalisation as they come roaring through. Glasman wants to ensnare capitalism in local associations that give people some powers of resistance against the moneymen. His rather clunky name for this is ‘democratic micro-entanglement’.

The other problem with liberalism, and the reason it is no good at this sort of micro-politics, is that liberals have a fatal weakness for abstraction. They prefer concepts to concrete experiences. In the end, they prefer nice ideas to real people. Glasman hates the way progressive movements tend to get fixated on ideals like justice, equality and fairness, as though these words had any power on their own. He is adamant that it makes a real difference that his campaign to improve the pay of contract cleaners and other disenfranchised workers in Central London was about getting them a ‘living wage’, not a ‘fair wage’. It is life as it is lived, not as it is refracted through the tidy mantras of political theory, that provides the only plausible guide for would-be reformers. It is the ‘ism’ in liberalism that sticks in Glasman’s craw. With his sights on the astonishingly narrow educational formation of the government and opposition front benches, he says: ‘PPE has a lot to answer for.’ So too do the philosophical heroes of the liberal tradition, like Kant, with his ‘intolerance of incoherence’. Liberals, for all their talk of pluralism and letting people do their own thing, don’t like it when life gets messy (Kant himself was a celebrated neat-freak). But if the messiness of real life is the only thing that stands between ordinary people and their disempowerment by the heartless forces of the global economy, then you have to muck in. No one should be afraid of getting nice ideas dirty.

There is nothing particularly original about any of this. As Glasman admits, he is harking back to an earlier period in Labour history, when the movement was centred on local struggles and community organisation, before it fell into the hands of Oxford-educated do-gooders who wanted to set the world to rights. There is more than a whiff of nostalgia about it. But for all that, it is curiously compelling. Much of what is collected in this volume (especially by current or former Labour politicians, including both Milibands, James Purnell, Hazel Blears, Jon Cruddas) is just the usual political blah-blah: Labour has to learn to admit its mistakes without diminishing its achievements, it has to find a new narrative to explain its vision for Britain, it has to harness the leadership potential that exists throughout the organisation not just at the top, it has to experiment with new ways of thinking without losing sight of what it really stands for, and much else besides. Whatever. But Glasman is that increasingly rare thing in contemporary politics, an authentic, and authentically strange, voice. He is not a pretty writer, but he is an arresting one. He calls his goal ‘socialism in one county’, and you feel he is only half-joking. He talks about reviving ‘self-government within the reformed institutions of the realm’ (is there anyone else on either side of the political divide you can imagine describing the country as a ‘realm’?).

He sums up the modern history of the Labour Party as an increasingly abusive marriage between a salt-of-the-earth, working-class dad, with his lived experiences and solid values, and an educated middle-class mum, with her good intentions and upwardly mobile aspirations. Not only is this touchingly politically incorrect, it’s also slightly bonkers: the dad we are told represents Aristotle (common good, balance), the mum Plato (ideal types, purity), and it’s the mum (in the form of all those Oxford-educated public schoolboys from Tony Crosland to Tony Blair) who has been meting out the punishment in recent decades, leaving the dad a shadow of his former self. Still, you can see what he means. The same is true of his most notorious flight of fancy: the idea that modern Britain needs to learn from what he calls ‘the Tudor commonwealth statecraft tradition’. Apparently the Tudors saw the realm as a hotchpotch of balanced and overlapping interests, inherently resistant to top-down reorganisation and needing to be nurtured through an Aristotelian conception of the common good. It’s not hard to quibble with the history (Henry VIII and his henchmen didn’t find the realm all that resistant to top-down reorganisation). But the phrase ‘Tudor statecraft’ stays in the mind long after the tired New Labour soundbites have been forgotten.

For a writer who isn’t afraid to say what he thinks no matter how odd it makes him sound, Glasman is strangely reticent on some pretty basic questions. One is the role of the Labour Party in achieving his vision. Glasman simply takes it for granted that if you want Tudor statecraft, Labour is the party to deliver it. This is because the Labour Party is the only progressive force in British politics that still has some Aristotelian DNA, if only poor henpecked dad could be persuaded to stop moping on the sofa watching Sky Sports and rediscover his mojo. It is the British dimension that’s the problem here. Glasman is big on Englishness (another of his faintly bonkers initiatives has been to try to open up a dialogue with the English Defence League). In his terms this sort of nationalism is OK, because it’s probably the most effective glue binding communities together. However, this sort of nationalism is not OK for Labour, since it is liable to destroy the party’s chances of returning to government in the foreseeable future. All the other parties can feed off the nationalist fragmentation of the UK in one form or another: the Scottish and Welsh nationalists, the Tories in England, and even the Lib Dems on the Celtic fringes, once the voters have returned them to their traditional role as a party of enraged but futile opposition. Labour has to extend its appeal across national borders if it is not going to get squeezed. To put it bluntly, the party needs Scotland to govern England. In that sense, it is Stuart statecraft that will be required, which is probably much less Glasman’s cup of tea (and a much less comfortable historical model, for obvious reasons). But without a convincing account of the reason different national communities need to be joined together in a larger whole, under a leader who can claim to speak for all of them, Labour may be finished as an electoral force.

That, though, raises a bigger question. Is democratic micro-entanglement consistent with wanting to win elections? Glasman, along with almost every other contributor to this volume, assumes that Blue Labour is a way of reinvigorating democracy. By democracy, I take it they mean electoral democracy or representative democracy or liberal democracy as it’s sometimes called: you know, the kind of thing we have in this country, with regular elections, professional political parties, a free press and occasional changes of government. Of course, the point of the Blue Labour critique is that this model of politics has become tired and needs some life put back into it. The assumption is that micro-democracy will be good news for macro-democracy, making it more dynamic and responsive. To use one of the ugliest words in the contemporary lexicon, Glasman and his colleagues believe that micro-democracy is scalable: get it right at the local level, and the rest will follow. But will it? Given that Glasman is not afraid of taking pot-shots at sacred cows, it’s surprising that he doesn’t really consider the alternative. What if macro-democracy is bad news for community empowerment, indeed makes it irrelevant? What if democracy – the kind of thing we have in this country – is the real enemy?

The closest Glasman comes to admitting this is when he says that it all started to go wrong for Labour after the 1945 landslide. ‘It could be said that in the name of abstract justice, the movement was sacrificed.’ But Glasman is careful to put the blame on the Attlee government’s taste for abstraction, rather than the simple fact of its election: it wasn’t winning that was the problem, it was that the wrong people won. In other words, he is separating out the liberal from the democracy in liberal democracy, so that he can carry on attacking the former without seeming to cast aspersions on the latter. But what if they can’t be separated out? In talking about ‘the movement’, Glasman is alluding to one of his heroes, the German social democrat Eduard Bernstein, who said at the end of the 19th century: ‘The movement is everything; the ends are nothing.’ Bernstein’s remark was directed at his Marxist colleagues, who liked to explain how wonderful things would be after the revolution and made no attempt to organise for justice in the meantime. Bernstein thought they were frightened of democracy because it was too messy, and as a result were squandering the chance to improve people’s lives, preferring to wait for a future that would never arrive. But as one of Bernstein’s most persistent critics, the French syndicalist Georges Sorel, pointed out, the problem with democracy was not that it was too messy. The problem was that it was too neat: it reduced everything to winning elections. This meant the movement would always be sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. It was hopeless to expect elected politicians to stand up to the forces of global capitalism, because elections gave them all the cover they needed to carry on mouthing high ideals while doing nothing except lining their own nests. Sorel went too far (he ended up convinced that Mussolini was the sort of community organiser democracy really needed). Still, seen from the early 21st century, there is something uncannily prescient about one of his most cynical remarks. ‘Democracy,’ he said, ‘is the paradise of which unscrupulous financiers dream.’

Glasman is not nearly so cynical. While the 1945 Labour government was going down the wrong track, he believes one country was showing how to get it right. West Germany embarked on a programme of democratic reform that embraced ‘subsidiarity, worker representation on works councils … the preservation and strengthening of vocational training … local relational banking and strong city government’. The Germans showed that this was a way not just to tame capitalism, but to improve it: ‘It turned out that greater vocational regulation led to higher levels of efficiency, worker representation to higher growth, local banking to more secure accumulation.’ Even better, all this was achieved on the watch of a British Labour politician who was not afraid to muck in. It happened, as Glasman puts it, ‘under the supervision of Ernest Bevin and the British occupation’. Thinking about how to rebuild Germany enabled Bevin to escape from the constraints of liberalism. What Glasman doesn’t say is that it also allowed him to escape from the constraints of democracy: this was democratic reform overseen by a politician who didn’t have to worry about getting elected, in a country under military rule. West Germany shows what can be done to revive democracy after the alternative has been tested to destruction. That is not the same as showing how to reform a functioning democracy from within.

Glasman also fails to ask the obvious question about Tudor statecraft: what killed it off? The answer is democracy, built on the principles of political representation that evolved during the 17th century. If 16th-century political life was based on a complex and overlapping patchwork of interests, this was only because no one had found the institutional means of simplifying it. Tudor statecraft was the product of a world in which those at the centre could never be sure of what was happening anywhere else, since reliable sources of information were negligible. It was government in the dark, which explains both the institutional diversity and the intermittent bursts of extreme brutality. ‘Representative government’ changed this by giving all sorts of different people a say in how they were ruled. It greatly enhanced the flow of information from local communities to the centre. But it also greatly enhanced the ability of rulers to claim to speak on behalf of everyone. Here is one of the enduring ironies of democratic politics: it makes available a mass of new information about how messy life is while producing a greatly simplified political structure in which small numbers of people can claim to speak for everybody. The world we currently inhabit has exaggerated this trend. We are drowning in information thanks to the democratic power of the web; at the same time, real political power is increasingly centralised and concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. The less information we have, the more varied our politics. The more we know about the way people live, the easier it is for politicians to gloss over the differences.

The ‘politics of paradox’ in the title of this book refers to the paradoxes of the Labour tradition as Glasman sees them. ‘Labour is robustly national and international, conservative and reforming, christian and secular, republican and monarchical, democratic and elitist, radical and traditional, and it is most transformative and effective when it defies the status quo in the name of ancient as well as modern values.’ The characteristic solipsism of those on the left leads them to assume that their experience of being pulled in different directions and struggling with their own conflicting impulses is what’s most interesting about modern politics. But we’re all pulled in different directions. The really significant paradoxes of modern politics are the paradoxes of democracy: localising and centralising, responsive and elusive, open and closed, adaptable and sclerotic, at its most transformative when something has gone badly wrong and at its most inadequate in the aftermath of its successes. Democracy does not always fail to stand up to capitalism (Sorel was wrong about that). It succeeded pretty well between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the oil crisis of the 1970s, but certainly there are no guarantees: it requires politicians to harness the power of the democratic state to broadly redistributive ends, which command the general assent of the people they represent. The evidence of the last 40 years is that this is becoming increasingly difficult. That’s what Glasman & Co are complaining about. But it is a mistake to finger liberalism and argue that democracy emancipated from liberalism would revert to its traditional role of protecting the working man. Democracy – having to win elections – is part of the problem too. Every Ed Miliband has to have his Tom Baldwin as well as his Maurice Glasman, and they are never going to find themselves in harmony. Democratic micro-entanglement will not change the character of macro-democracy. If anything it is a retreat back down the scale and back into the past, before the genie of liberal democracy escaped from the bottle. It is not nostalgic so much as defensive. In trying to rescue democracy from liberalism, Blue Labour is effectively giving up on macro-democracy, preferring to organise against the power of the liberal democratic state rather than trying to co-opt it. It might win some of these battles at the local level, but I don’t see how it can win the wider war. The lesson of history is that macro-democracy – liberal democracy – wins in the end.

There is an alternative to micro-democratic defensiveness. One of the dispiriting things about this volume is how parochial it is: not just in the sense of being preoccupied with local politics, with the psychic traumas of the left and with Englishness, but in its rejection of all things European (Glasman wants to learn from the Germans, but he certainly doesn’t want to get together with them). Yes, the EU is in crisis and, yes, the euro in its present form is probably finished. But such crises are democratic opportunities. Now is the time for Labour politicians thinking outside the box to look to macro-democracy at the European level, with a view to utilising the power of politicians who can claim to speak for the peoples of Europe to stand up to the depredations of global capitalism. This may be utopian, but at least it is not defeatist. The biggest mistake made by a Miliband in recent years was the decision by David to forego the opportunity to become EU high representative on foreign affairs, choosing instead to stay and fight his brother for the Labour leadership. At some point a politician is going to capture the attention of the wider European public and appear before them as their political representative. If not now, when? I don’t agree with Tony Blair about much, but his quixotic and self-defeating (because assumed to be self-aggrandising) call for an elected president of the EU was that other increasingly rare thing in contemporary politics: a genuinely radical call for change from a mainstream liberal democratic politician (albeit one who doesn’t have to worry about his own national electorate anymore). It is a far more ambitious and appealing idea than anything provided by Glasman, for all his quirky charms. That it comes from Blair does not mean that it is wrong. These are the paradoxes of democratic politics.

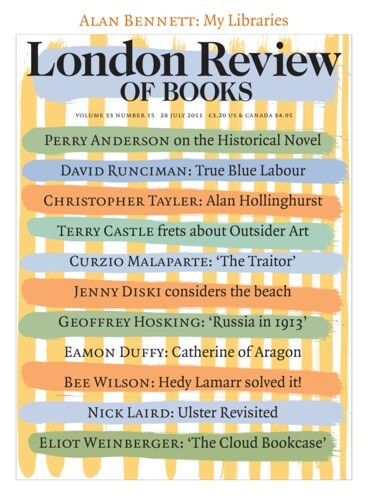

On the LRB blog, 21 July - David Runciman: So Much for Blue Labour

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.