Henry James met Rupert Brooke on a visit to Cambridge in June 1909, having been invited there by some young admirers who made him feel, he wrote in a letter, ‘rather like an unnatural intellectual Pasha visiting his Circassian Hareem’. Brooke, in a white shirt and white flannel trousers, took charge of a punting trip on the Cam. ‘Oh yes,’ he said later, ‘I did the fresh, boyish stunt, and it was a great success.’ James sent thanks to all concerned, ‘with a definite stretch towards the Rupert’, and after the poet’s death in 1915 he agreed to write a preface to Brooke’s Letters from America. He didn’t get completely carried away – one sentence worries about Brooke seeming a ‘spoiled child of history’ – but he was old and ill, queasily supportive of the war effort and moved by his memory of the young man on the river ‘with his felicities all most promptly divinable’. Under the circumstances, he told Edward Marsh, the poet’s literary executor, he had read Brooke’s war sonnets ‘with an emotion that somehow precludes the critical measure’.

Eddie Marsh, too, was greatly struck by Rupert’s ‘radiant, youthful figure’, which he first saw in a student play in 1906: ‘After 11 years,’ he wrote, ‘the impression has not faded.’ Promoter of Georgian poetry by night and private secretary to Churchill by day, he helped Brooke get his commission in the Royal Naval Division – which was how the poet came to die from an infected mosquito bite while steaming towards Gallipoli – and had a lot to do with Brooke’s apotheosis as a poster-boy for self-sacrifice: Churchill’s threnody on his ‘classic symmetry of mind and body’ etc. As both Georgian and civil servant, Marsh had no problem with those who, as the New Statesman soon put it, pictured Brooke as a ‘blend of General Gordon and Lord Tennyson’. To the disgust of Brooke’s Cambridge and Bloomsbury acquaintances, he promoted him as a clean-cut poet-patriot long after the sell-by date for enthusiastic lines about soldiers pouring out ‘the red/Sweet wine of youth’.

Mary Brooke, Rupert’s mother, nicknamed ‘the Ranee’, also had an idealised view of her son, but she was more alert to the danger of a backlash. She found something vulgar and inexplicable in Marsh’s impassioned concern for his dead protégé’s fame, and took offence at his lack of reticence about Brooke’s woman friends. Her co-operation foundered on Marsh’s memoir of Brooke, which was published in 1918 after many delays. Marsh – who obligingly filled it with clumsily worded letters from the likes of Hubert Podmore, a Rugby contemporary of Brooke’s and self-confessed ‘awful Philistine’ – was baffled by her hostility, which was made all the more frustrating by her obliviousness to his tactful whitewash of Brooke’s entanglements with various ‘neo-pagan’ girls and admiring Bloomsbury boys. Brooke had turned on the last group, scorning them as ‘half-men’ in his sonnet ‘Peace’, and during a nervous breakdown he had in 1912 he blamed women, Jews and homosexuals – Lytton Strachey in particular – for much that was wrong with the world, an episode that neither Marsh nor Mrs Brooke would have seen a need to publicise.

In Keepers of the Flame: Literary Estates and the Rise of Biography (1992), Ian Hamilton quotes Brooke’s Rugby and Cambridge friend Geoffrey Keynes on the underlying causes of the Eddie-Ranee stand-off:

Brooke’s unmanly physical beauty was often taken as an indication that he was probably a homosexual … It had, of course, been far from Marsh’s intention to produce any such impression. He had been deeply attached to Rupert, as he was to many young men, but lived himself in a sexual no man’s land whose equivocal aura pervaded the Memoir and contributed to the Brooke ‘legend’. Mrs Brooke had probably sensed this even though she might not have been able to put it into words.

When Mary Brooke died in 1930, her will replaced Marsh with Geoffrey Keynes as chief literary executor. Deeply wounded, Marsh handed over his Brooke materials, though after his death his attic gave up a container labelled ‘The Rupert Trunk’ which contained, among other things, the poet’s tie and handkerchief and ‘several copies of a pamphlet called Sexual Ethics’. Meanwhile, Keynes set out to emphasise Brooke’s ‘wholly masculine character’, as he put it. An authorised biography appeared in 1964, followed by Keynes’s resoundingly heterosexual Letters of Rupert Brooke in 1968. But less reserved researchers were on the case too, and they soon turned up, as Hamilton says, documents ‘“equivocal” enough to have earned for Brooke a small foothold in Gay Studies’. The star turn was a letter first printed in full in Paul Delany’s The Neo-Pagans: Friendship and Love in the Rupert Brooke Circle (1987). Writing to James Strachey, Brooke describes some encounters with his fellow Rugbeian Denham Russell-Smith:

We had hugged & kissed & strained, Denham & I, on & off for years – ever since that quiet evening I rubbed him, in the dark, speechlessly, in the smaller of the two Small Dorms. An abortive affair, as I told you. But in the summer holidays of 1906 & 1907 he had often taken me out to the hammock, after dinner, to lie entwined there.

He goes on to describe losing his virginity with Russell-Smith in the autumn of 1909: ‘Quite calm things, I remember, were passing through my brain. “The Elizabethan joke ‘The Dance of the Sheets’ has, then, something in it.” “I hope his erection is all right” … and so on.’ Wherever he might have placed himself on the sexual spectrum if he hadn’t died at the age of 27, Brooke was, the letter leaves little doubt, a big show-off.

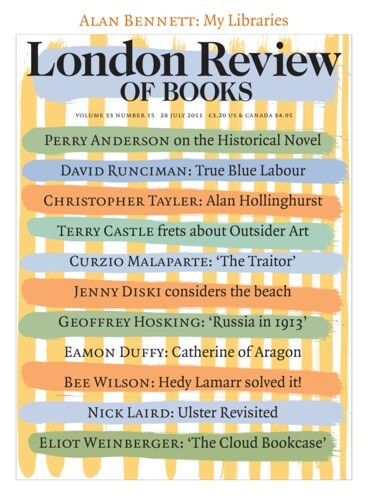

Alan Hollinghurst has always had a soft spot for show-offs. In his first novel, The Swimming-Pool Library (1988), the narrator reads a review of a Shostakovich concert that he skipped to spend time with a newish boyfriend, who ‘would have been sitting on my face just as the “terminal introspection” commended by the reviewer was at its most abysmal.’ Hollinghurst is also interested in buried artistic back-stories, piecing together a gay high-cultural tradition in The Swimming-Pool Library and putting imagined painters and poets in the background of The Folding Star (1994), among them a wizened Georgian called Perry Dawlish. He’s interested in ‘the honoured quaintness of being English’, as it’s called in The Spell (1998), and in the caste-markers attached to it: one character in that novel has ‘what he thought of as an upper-class distrust of niceness’. And, of course, he’s interested in what Nick Guest, the James-fixated central character in The Line of Beauty (2004), thinks of as ‘the homosexual subject’.

In The Stranger’s Child he weaves a number of stories around the idea of Brooke and his posthumous fortunes, detailing the lives caught up in the reputational arc of a Brooke-like poet called Cecil Valance between 1913 and 2008. Both world wars, fought offstage, have effects that ramify throughout the novel, as do changing attitudes to gay people and to biographical disclosure. Hollinghurst writes with amused tenderness about Rupert Trunk-type phenomena, investing them with dignity and pathos, but he also puts both hands on opportunities for irony, arch humour and, intermittently, an un-Jamesian directness. James described Brooke as ‘extraordinarily endowed and irresistibly attaching’; Valance, a former lover says, ‘had an enormous cock’ and ‘would fuck anyone’.

The book’s opening section, ‘“Two Acres”’, is set in 1913. Two Acres is a pleasant house in Stanmore Hill inhabited by Freda Sawle, a youngish widow, and her children Hubert, George and Daphne. Writing in the third person, with each chapter tied to one character’s point of view, Hollinghurst stages a weekend visit from Cecil, who’s at Cambridge with George and has arranged for him to join the Apostles. Cecil is an aristocrat, unlike Brooke, as well as a rising poet: he’s the heir to Corley Court, a late Victorian pile in Berkshire about which he has written some poems, and from which George has brought back word of skilled valets and ‘jelly-mould domes’. Freda, though discomposed by having such a grand visitor, is happy to see the warmth and animation Cecil has brought out in her shy middle child. Daphne, who’s 16, is excited to meet a poet. Hubert, the oldest, is less sure about that: he is not, as he explains in a clumsily worded thank-you note to their rich and generous neighbour Harry Hewitt, an ‘aesthetic’ sort of fellow. But he’s determined to do his best.

‘Candour is our watch-word!’ George exclaims with ‘lurking fury’ when his family inadvertently reveal that he’s blabbed about joining a prestigious secret society. In truth, nearly everyone at Two Acres is so clueless about the powerful sexual charge in the air as to make notions of candour seem somewhat redundant. Even Jonah, a young houseboy who enacts one of Hollinghurst’s trademark pants-sniffing scenes in the course of unpacking Cecil’s body linen, can’t get a fix on the nature of his feelings. Nor can he make sense of the enigmatic poetic off-cuts – ‘As wood-lice chew willows, So do mites bite pillows’ – that he retrieves from Cecil’s wastepaper basket. George is attached to Cecil ‘in the Cambridge way’, someone notes. When the pair sneak off to the woods for sex, the poet calls their grapplings ‘a bit of Oxford style’. ‘I have a horrible habit, anathema to polite society, which can only decently be pursued out of doors, under cover of darkness,’ Cecil announces after dinner, producing a cigar case. Daphne follows the boys outside and finds them entwined in a hammock. Cecil cajoles her into trying his cigar. ‘I’m smoking Cecil’s cigar too,’ George comments ‘in his most paradoxical tone.’

Hollinghurst lays out these goings-on in a slightly diluted version of his usual rich style, adjusted to accommodate the focal characters. As in The Spell, he uses shifts of perspective to get a steady crackle of irony going, but this time round he writes from women’s points of view as well as men’s. Daphne – whom it’s hard not to compare to Briony in Ian McEwan’s Atonement – overhears George applying a Strachey-esque term for a heterosexual man to Hubert: ‘A womaniser … ! The word lay, sinuous and poisonous, in the shadowy borders of Daphne’s vocabulary.’ Sisterly intuition tells her that George must be a womaniser: how else to explain his blushes when she asks if he has a girlfriend? Later, when Cecil seizes and kisses her, ‘the hard shape of the cigar case in his trouser pocket thrusting against her stomach’, she wonders at his unheard-of use of his tongue. ‘Maybe George, if he did have a girl, had had a go at it. She imagined asking him, and the secret fact of it having happened with his best friend made the idea slyly amusing.’

Further ironies accumulate around the figure of Harry Hewitt, who, the family hope and fear, plans to marry Freda. Hewitt has advanced tastes in art and pays court to her, it seems, by lavishing gifts on Hubert, who’s puzzled by his more physical displays of affection. Freda, oppressed by the Hewitt conundrum and by Cecil’s ‘pagan’ dew-dabbling activities, arms herself with a large drink before a poetry reading. She starts falling asleep as Cecil recites a bit of his own work (‘Love comes not always in by the front door’ is one memorable line, declaimed in a ‘homiletic’ fashion), waking up in time to hear Tennyson’s lines from In Memoriam about a landscape growing ‘familiar to the stranger’s child’. Another poem, however, dominates the weekend: a ‘Grantchester’-like effort called ‘Two Acres’ that Cecil writes a draft of in Daphne’s autograph book. Everyone except George – who’s seen other drafts, addressing him – assumes that Daphne is the ‘you’ in this slice of Georgian pastoral, quoted here and there, and wittily concocted by Hollinghurst, but never given in full.

These encounters with poetry are joined by other woozy perceptions as the novel tracks the Sawles and Valances down the years, depicting familial and literary memory as hopelessly blurred and manipulable. Section 2, ‘Revel’, takes place at Corley in 1926. Teasingly giving information out piecemeal, as he does at the start of each succeeding section, Hollinghurst lets the reader work out what’s been happening. Daphne has married Cecil’s younger brother, Dudley, a war-damaged writer and a sarcastic drunk. Cecil ‘fell’ in 1916 – in action, unlike Brooke – and lies in Corley’s chapel under a sculpted tomb erected by his mother, a grim dowager nicknamed ‘the General’. George has married a humourless fellow academic, which Freda feels guilty about: she confronted him after reading his letters from Cecil. With much boozing, heartache, child-neglect and adultery, they all assemble for debriefing by Sebastian Stokes, ‘man of letters and discreet Tory fixer’. ‘Sebby’ is writing Cecil’s biography, having been excited by ‘his lordly thrust and toss of the pole and intermittent recital of sonnets’, as George recalls tartly, on a punting trip in Cambridge. At the same time, Dudley is having the house’s Victorian interiors boxed in and painted white.

Like the opening section, in which there are rumours of war, ‘Revel’ is shadowed by a historical event. ‘It was on the very eve of the General Strike,’ George’s wife, a historian, remembers years later, adding inaccurately: ‘We talked of little else.’ The next two long sections – capped by a coda set among the iPhones and civil partnerships of 2008 – are set on the eve of, respectively, the Sexual Offences Act 1967 and the Aids crisis and collapse of the postwar consensus. With the exception of one chapter, Hollinghurst moves away from Daphne’s consciousness, showing her and her children mostly through the eyes of Paul Bryant, who in 1967, clever but kept from university by the need to support his mother, starts work in a bank managed by Daphne’s daughter’s husband. Corley Court is now a prep school and one of the teachers, Peter Rowe, inducts Paul into Valance Studies in the course of a revelatory love affair. As a jobbing reviewer in 1979-80, Paul starts work on a lid-lifting biography of Cecil, approaching the surviving cast with varying levels of success. Finally, in 2008, we’re shown the ambiguous results of his work in an accelerating run of narrative surprises.

Cecil isn’t Brooke, but he has a lot in common with him, a fact that Hollinghurst addresses by having characters compare their looks: Cecil is darker, less beautiful, more seductive. Remembered chiefly for ‘Two Acres’, to which he later adds a warlike quatrain likened by George to ‘a gun-emplacement at the bottom of the garden’, he becomes a public monument, quoted by Churchill. By 1926 fresh paint might be needed – Sebby alludes to Pound and Eliot – and by 1967 he’s Common Entrance fare, seen as ‘awfully imperialist’ by student types and disparaged for his ‘tendency to sonorous padding’. Yet Michael Holroyd’s work on Strachey has stirred up hearsay and a sense of a coming ‘age of documentation’; at Corley, a fallen ceiling affords a glimpse of camp Victorian splendours. When Paul snoops round Two Acres in his role as a biographer, he pisses in the overgrown garden from a need that’s ‘territorial as much as physical’. By the end of the book, Two Acres has been demolished and the poem named after it is mostly a footnote to someone else’s ‘milestone works in Queer Theory’.

Such works, we understand, aren’t what Hollinghurst has in mind when he speaks of ‘the homosexual subject’. And there are further compound ironies on his balance sheet. Paul’s provincial life in 1967 isn’t much to write home about: Ian Fleming paperbacks announcing themselves as aimed at ‘warm-blooded heterosexuals’ aren’t in short supply, but for a young gay man there’s only Angus Wilson, plus ill-informed efforts to imagine scenes that, ‘as far as he knew, had never been described at all’. So, in that respect, bring on the iPhones. Paul’s later researches bring the ‘priapic figures in the trees and bushes’ of Cecil’s English idyll into the open, linking up with the gay pastoral ideal evoked in The Folding Star and The Spell. On the other hand, few characters care or notice, and a strong current of melancholy flows round the novel’s suburban landscapes, outmoded poeticisms, unloved Victorian buildings, and absent, dead, suicidal or defective fathers. The literary-biographical enterprise is also subjected to unflattering comparisons – to the General’s sad, book-based séances, for instance, and a walk-on character’s jerkily animated website on which pictures of the famous dead are made to speak.

Hollinghurst has never been the kind of writer who tries to conceal effects and narrative manipulations. As well as the parallels between Cecil’s reputation and the Sawle and Valance residences, The Stranger’s Child has an intricate armature of doublings, foreshadowings, James-style withholdings, Proust-style ‘ways’ (‘the country way, and the suburban way’) and leitmotifs, one of them literally Wagnerian (Daphne is associated with Senta’s ballad from Der fliegende Holländer). The made-up cultural figures are expertly done, starting with Cecil, whose name his brother pronounces, per toff usage, ‘Sizzle’. ‘Valance’ has suitably martial echoes but also means a bed skirt, an item associated with old-fashioned coverings-up. The period details work well, the conversations unspool effortlessly, and there are many good jokes. Yet for stretches the pressure seems to drop. It’s partly the cumulative effect of so much superb writing – you start taking it for granted – and partly a problem to do with Paul, who’s a lower-wattage character. Hollinghurst has good reasons for making him a bit dim, but Paul is allowed fewer of the sharp perceptions given, for example, to Danny in The Spell, a comparably shallow figure.

The Stranger’s Child is also milder than his previous novels when it comes to what he probably wouldn’t call the heteronormativity of the world at large. There are more women, fewer sex scenes and fewer of the entertaining put-downs – ‘The other man was a morose heterosexual with a pudding-basin haircut and a copy of Mayfair in his locker’ – with which he once countered the disdainfully or cursorily observed gay characters of other books. I missed the sense you get from his earlier novels of an utterly authoritative, unembarrassable voice being brought to bear on disparate areas of experience: Louis Quinze escritoires, cocaine and Ecstasy rushes, a suburban funeral, cruising at Hampstead Ponds. Fewer areas in the new book haven’t been worked over by writers of Hollinghurst’s stature, and there’s a faint note of critic-appeasingness – not a note you’d think of him as needing to strike – in the way he reins in the characters’ knowledge of music and architecture as well as sex. He’s very funny, though, about the self-flattering fantasies that reviewers and would-be biographers are prone to, throwing in a useful shoplifting tip for those with access to editorial stationery. In addition to providing an elegant ending, he makes the book into an elegant gesture: a critic-pleasing novel depicting critics and biographers as being essentially parasitic and, even when right, point-missingly or irrelevantly so.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.