For more than three decades, the makers of American opinion have evaded the full significance of the Vietnam War – the mendacity, the brutality, the futility. The collective amnesia has been exacerbated by a counter-offensive from the right. Like German nationalists after World War One, American revanchists tell a story of a stab in the back: they insist that the American counter-insurgency was on the brink of victory when it was done in by a coalition of liberal journalists and cowardly college students, who undermined the nation’s will to fight. As a veteran of both the US navy and the peace movement during that time, I remember a different story, one that includes the impossibility of the military mission, the ubiquity of dissent among enlisted men and junior officers, and the sympathy of anti-war activists for young men caught up in the war machine. The notion that opponents of the war were hostile to ordinary soldiers is simply false. Yet the stab-in-the-back narrative persists.

This emerging conventional wisdom equates criticism of imperial misadventure with a failure to ‘support our troops’. The emphasis on lost opportunity has also helped to justify the revival of Vietnam-style counter-insurgency in Afghanistan, with ‘clear and hold’ operations aimed at ‘winning hearts and minds’ – as if these phrases were not shrouded in self-parody, as if the strategy they describe had not ended in catastrophe. Public memory is short.

Outside policy circles, one might hope to find a richer repository of inconvenient truths. Yet here too the results are disappointing. A few novelists have made something lasting of their war experience. But even the most penetrating accounts, as Christian Appy observed in Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides (2003), have remained narrowly focused, with the war ‘reduced to stories about small units of American infantrymen fighting a silent, nearly invisible enemy at a single moment in time. Not only are the Vietnamese routinely left out, but most of the Americans who made the war the contentious experience it was are also missing’ – notably the anti-war protesters, whose seriousness and diversity are ignored in favour of caricature. The popular memory of the war betrays a national narcissism. ‘Even when we believe we have confronted the war’s most horrible features,’ Appy concluded, ‘we often have been doing little more than licking our own wounds.’

Licking one’s wounds can be a necessary ritual. No one can deny the damage done by that vile war, not only to the Vietnamese people and the US soldiers, but also to war resisters and even deserters – many of whom sacrificed career and community out of loyalty to principles that outweighed mere obedience to military authority. The problem arises when it is assumed that the US combat veteran’s perspective provides the only true account of the war’s significance. The grunt’s-eye view has been progressively sanctified since the ending of conscription in 1973; as military experience has become ever more remote from most Americans’ lives, the tendency to exalt armed service has intensified. Since 9/11, a cult of the warrior has settled over America like morning fog over the Mekong Delta.

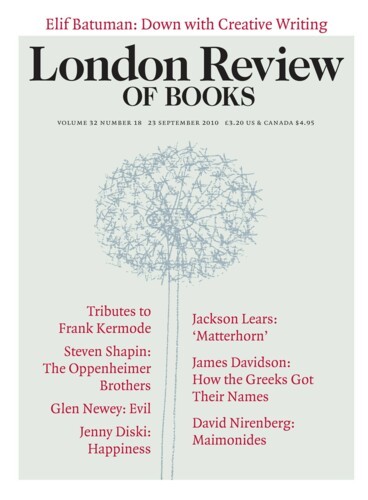

This resurgent popular militarism may help to explain the extravagant American praise for Karl Marlantes’s Matterhorn. Reviewers and publicists have missed no opportunity to point out that Marlantes is not only a Rhodes scholar from Yale but also a ‘highly decorated Vietnam vet’. His author’s note lists all 16 of his medals – ‘the Navy Cross, the Bronze Star, two Navy Commendation Medals for Valour, two Purple Hearts and ten Air Medals’ – and his publisher’s press kit includes a copy of the government document that awarded him the Navy Cross, citing ‘his courage, aggressive fighting spirit, and unwavering devotion to duty in the face of grave personal danger’. There is something disturbing about this effort to turn military medals into book sales – and to pre-empt criticism by brandishing the author’s heroism. But the publisher’s strategy has succeeded. American reviewers have greeted the book as if it were the second coming of All Quiet on the Western Front. In the New York Times Book Review, Sebastian Junger described Matterhorn as ‘one of the most profound and devastating novels ever to come out of Vietnam – or any war’; it ‘may well serve’, he said, ‘as a final exorcism for one of the most painful passages in American history’.

It is necessary to separate Matterhorn from the inflated publicity surrounding it. Considered as a novelist (rather than an exorcist), Marlantes does many things well. He captures the camaraderie and fear and occasional exaltation felt by men at war. He creates several convincing characters, and makes the reader care what happens to them. Despite his weakness for wooden phrases and his tendency to labour the obvious, he tells a gripping story. And by demonstrating the futility of American strategy, he debunks the right-wing narrative of lost opportunity – no small achievement in these amnesiac times. It is when he strains for profundity that the trouble starts.

Matterhorn follows a single US marine unit, Bravo Company, as its men attempt to obey the contradictory, self-cancelling and deeply confused orders of their superior officers. After setting up a complex system of fortified bunkers on top of a steep and nearly impregnable hill, the ‘Matterhorn’ of the title, Bravo Company is told to abandon it to search for North Vietnamese Army units in the valley below, and then, when the NVA have taken the hill, to retake it from them in the novel’s climactic battle scene. The marines struggle with leeches and jungle rot. They elude snipers and landmines – or don’t. They curse the politicians and generals who sent them there and the anti-war protesters who want to bring them home. They search for the NVA, though they almost never see them. And where these marines are, in the Central Highlands, there is not a Vietnamese civilian in sight. No one but North Vietnamese soldiers to fight up there – ‘fucking pros’, as one marine says. No need for the messiness of counter-insurgency conflict.

All this fits into familiar American representations of the war: the isolated unit, the free-floating rage, the deranged tactics, the invisible Vietnamese. Yet despite its narrowness Marlantes’s narrative preserves a political edge, refuting on every page any retrospective claims that the war could have been ‘won’. He makes the point that his marines respect the NVA because they know the Vietnamese are fighting for their country and are never going to quit. Dissecting the body-count strategy, he reveals its corrupting effects on truth and tactics. Anything could be justified in the name of the single overriding imperative: ‘Kill gooks.’ But when Marlantes turns towards politics at home, problems arise. His marines see the peace movement through a cloud of pop-cultural clichés: anti-war activists are all rich, cynical and self-absorbed.

Matterhorn is a Bildungsroman charting the growth of the protagonist, Second Lieutenant Mellas, from callow careerist to chastened warrior. Through Mellas, Marlantes tries to make meaning out of meaningless suffering. The effort recalls Sartrean existentialism as well as a peculiarly modern version of militarism, more severe and paradoxical than the popular reverence for ‘our troops’ – a free-floating relish for combat.

The Supreme Court justice and Civil War veteran Oliver Wendell Holmes outlined this ‘soldier’s faith’ to a Harvard audience more than a century ago. Civilians, he said, might succumb to ‘the temptations of wallowing ease’ – but not men like himself, who had fought. ‘We have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top.’ This was what war came to mean – the passionate camaraderie of combat – in an age when larger structures of meaning were tottering. ‘I do not know what is true,’ Holmes said.

I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has no notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

The very emptiness of this warrior ethos made it adaptable to imperialist and fascist agendas. Heroism for its own sake is a dangerous game.

Marlantes may or may not have read Holmes, but Matterhorn is in the Holmesian tradition. Though Marlantes recognises the mendacity of the policy-makers (both civilian and military) and even hints at the meaninglessness of the medals they give out, in the end he takes refuge in the warrior ethos. For Marlantes, as for Holmes, war’s mindless slaughter allows combatants to feel ‘the passion of life to its top’. A war’s political purpose (or lack of one) is less important than its capacity to connect us to our deepest selves and to our comrades, through the supreme authentic experience of killing and being killed.

The tale of self-development begins when Mellas reports to Bravo Company’s command post. He is a smalltown kid from Oregon who went to Princeton on a military scholarship (a free ride in exchange for four years of active duty). Combining humble origins with elite credentials, he nurtures political ambitions: combat service in Vietnam will look good on his résumé. So will a medal or two. Like any green platoon commander, he wants to fit in, to be one of the guys. But he also wants to advance his career. ‘It would look bad on his fitness report if he had a lot of cases of immersion foot’ – a result of constant marching through cold water. Gradually he becomes more attuned to his men’s welfare, less concerned with appearances. A key figure in the shift is Lieutenant Hawke, his charismatic predecessor as platoon commander who is now company executive officer. The men would follow Hawke anywhere. He becomes a model for Mellas and a voice of vernacular wisdom in the novel.

Early on there are signs of the war’s futility. As in Conrad’s novels of empire, human exertions are quickly negated by the overwhelming fecundity of tropical nature. ‘The company left no more mark on the jungle than a ship’s wake on the sea,’ Marlantes writes. Advanced technology is repeatedly undone by weather and topography: fixed-wing aircraft are useless in the highlands, and helicopters are vulnerable to hidden sniper and artillery fire. Impossible terrain and an invisible enemy mean constant vulnerability to ambush and frequent deaths by friendly fire. A sense of pointlessness envelops every slog through the dense jungle. ‘Just tell me where the gold is,’ mutters the machine gunner Hippy. ‘Just some fucking gold so it all made sense.’ Confronted with a particular tactical absurdity, the men can only murmur: ‘There it is.’

Even senior officers fitfully recognise the incoherence of a strategy entirely based on inflated body counts. Only Major Blakely, the crisply bureaucratic ‘problem solver’, is untroubled by doubts about larger aims. He knows how to play by the numbers. ‘There was no doubt in Mellas’s mind that the fucking prig would be a general one day.’ Blakely’s immediate superior, the bellicose and alcoholic Colonel Simpson, says the company must retake Matterhorn ‘to redeem their honour and get their pride back’. The language is hollow: Simpson is trying to salvage his last chance for promotion by piling up Vietnamese bodies. When what is left of Bravo Company finishes off the last NVA bunker on Matterhorn, Blakely and Simpson, watching from a safe distance through field glasses, burst into cheers. ‘Magnificent. I wish I’d had a movie camera,’ Simpson says over the radio. Mellas, injured and enraged, draws a bead on the colonel with his M-16, but Hawke tackles him at the last second.

Apart from this incident, dissent in the ranks is race-based. From Marlantes’s account, one would never know how pervasive anti-war protest was among both white and black soldiers, ranging from individual and collective refusal of combat, to the ‘fragging’ (or assassination) of officers by surreptitiously triggered grenades, to the recording and reporting of atrocities. In Patriots, an air force medic stationed at Cam Ranh Bay hospital in 1969 remembers treating the civilian victims of American violence, an experience that provoked him to post signs on the hospital bulletin board saying: ‘Don’t Do What They Tell You, Tell What They Do.’ His defiance, he later realised, ‘was a tiny splinter in the midst of a sort of uprising among soldiers’. But in Matterhorn only black soldiers are political, and despite a few grumbles about their racial kinship with the ‘gooks’, their protest is mostly against unfair treatment by the military rather than the war itself.

Marlantes respects the black characters without sentimentalising them. He has an ear for African American speech and an eye for racial rituals, as well as a keen sense of how personal humiliation can lead to racial violence. When a black marine called Parker refuses to cut his hair, the bullying racist Sergeant Cassidy cuts it for him. Parker, simmering silently, rigs one of Cassidy’s grenades to explode unexpectedly. Cassidy discovers the attempted fragging (though not its perpetrator) before it happens. Shortly afterwards, ‘humping’ through the bush, Parker comes down with convulsions and a rapidly rising fever; it turns out to be a fatal case of cerebral malaria, not something the medics have ever seen before. As Parker lies dying on a litter, carried by his comrades through a stream, he confesses to the attempted murder. Cortell, a black rifleman, offers the terrified Parker forgiveness by baptising him on the spot. ‘How can I go to hell?’ Parker asks.

‘You ain’t goin’ to hell. That where you been. You just ask Jesus to forgive you.’ Cortell gently poured another handful of water onto Parker’s head.

‘I can’t.’

‘Then I will.’ Cortell let a third handful of water drain onto Parker’s head. He placed his helmet on Parker’s stomach. Then he bent over the helmet, hands folded, and closed his eyes. ‘Lord Jesus. Sweet Lord Jesus. You know this man Duane Parker who is about to come to thee. He has been a good man. He has seen some bad times. Now he asks you with all of his heart for you to forgive him so he might come to thee and thy glory. Lord Jesus, I know you hear me, even here in this river. Amen.’

The scene is extraordinary, but the narrative leads elsewhere. While Parker is being reborn in Jesus, Mellas is en route to his own secular rebirth, his move away from shallow civilian values and towards a warrior ethos. The deeper he penetrates the jungle, the more alienated he feels from the folks back home ‘gorging themselves in front of their televisions’, and especially the men who managed to evade the nightmarish absurdity he has chosen. He is convinced that he and his comrades are somehow ‘better people’ than those who refused to go. Puzzling as this conviction may be, given Marlantes’s harsh critique of the war, it lies at the heart of Mellas’s militarist creed. Holmes, for one, would understand.

As for anti-war activists, Marlantes can’t take their convictions seriously. Or so one infers from the uniformly derisive references to the peace movement made by the members of Bravo Company. Hawke leads the way in his disdain. Though he is a graduate of the University of Massachusetts, he gets to deliver the formulaic working-class view on protest. He cannot believe that someone with Mellas’s privileged educational background would have chosen to join the marines. ‘All the rest of your hoity-toity buddies joined the navy, didn’t they? At least the ones that weren’t screwing their brains out and smoking dope at some peace rally.’

In a crucial scene, Mellas watches his comrades race to board a helicopter and whispers the Marine Corps motto: ‘Semper Fi, brothers.’ Then he remembers a conversation at his college eating club. Princeton boys and Bryn Mawr girls had scoffed at all the military talk of honour, and Mellas had joined in,

not wanting to be thought of as whatever bad thing they thought a warrior was. Protected by their class and sex, they would never have to know otherwise. Now, seeing the Marines run across the landing zone, Mellas knew he could never join that cynical laughter again. Something had changed. People he loved were going to die to give meaning and life to what he’d always thought of as meaningless words in a dead language.

Semper fidelis.

Still he wavers. After realising that he has killed one of his own men, he stares into his soul and sees himself as nothing but ‘a collection of empty events’. He considers playing dead as an animal might, to stay alive, but then rejects the idea and cries with ‘the rage and hurt of a newborn child, at last, however roughly, being taken from the womb’. He knows then that he will not play dead. Instead, ‘he’d choose to stay on the hill and do what he could to save those around him.’ Killing is redeemed by community.

But the warrior ethos is about individual as well as communal experience. Mellas gradually recognises that mortal combat can be exhilarating. This takes time. After his first firefight, he feels merely ‘a strange exultation, as if his team had just won a football championship’. Soon he realises that being on patrol, expecting an ambush, made him feel ‘wonderfully powerful and dangerous’, with his senses ‘keenly alive’. Even so he refuses to let one of his men kill a wounded NVA soldier because ‘it’d be murder.’ Eventually, during another firefight, Mellas is ‘transported outside himself, beyond himself … this brilliant and intense fear, this terrible here and now, combined with the crucial significance of every movement of his body, pushed him over a barrier whose existence he had not known about until this moment. He gave himself over to the god of war within him.’ War as authentic experience: this is the nihilist edge of modern militarism, unalloyed by moral pretension.

Marlantes sidesteps the nihilism by coupling it with communal redemption. But redemption is not always available, and the spectre of nothingness looms. ‘It was all absurd, without reason or meaning,’ Mellas thinks. ‘People who didn’t even know each other were going to kill each other over a hill none of them cared about.’ It is a ‘great joke’, he concludes, that he ‘would probably get a medal for killing one of his own men’, just as Nixon ‘would probably get re-elected for doing the same thing on a far larger scale’. His despair deepens when he is sent to a hospital ship for treatment of an eye injury.

He meets a red-headed nurse from a small New England town. They reminisce about the pleasures of berry-picking until Mellas breaks off and imagines the idyllic scene being interrupted. In his mind’s eye he watches as a car pulls up, full of drunken, beefy guys armed with rifles. They drag the berry-pickers off to the dump, where they organise a dangerous game. The berry-pickers

have to crawl through the dump from one end to the other. Whenever we come across a can whose lid we cannot see, we must pick it up and show it to the men with the rifles. If the can turns out to be empty, we can continue. If it turns up unopened, then we get killed … We even get ribbons if we’re particularly clever … And one by fucking one … the guys you picked berries with get killed. And you just keep being clever.

There is no redemption in this narrative; ‘The game goes on and on and on.’ Frightened by his rage, the nurse tries to sympathise but backs away. Mellas is left alone with his awareness of the criminality of the game and the triviality of the prizes.

Return to the company brings a lifting of despair. In a half-drunk conversation with Hawke, Mellas admits he’s ‘“been feeling bad because I enjoy killing people”. Hawke laughs quietly. “At least you’re over the hump on that one. It’s the people who don’t know it who are dangerous. There’s at least two hundred million of them back in the world. Boot camp doesn’t make us killers. It’s just a fucking finishing school.”’ Hawke’s ‘number-one squaw’ back home has dropped him because she finds it ‘inconceivable’ that she could do what he’s done. She and the other civilians just don’t get it. ‘“None of them had met the mad monkey inside us,” Hawke added. “But we have.” “There it is,” Mellas said.’ We are all capable of taking pleasure in killing, and if we were honest we would own up to it. War, as organised violence, is absurd, which is what makes it the ultimate authentic experience.

This perspective is disturbing for many reasons. One is the misogyny at its core. Hawke’s disdain for his ex-squaw is symptomatic; he and his fellow officers complain often about college girls, about their class-bound moral arrogance and disdain for men in uniform. Mellas ‘really hated women at some level, maybe because they stayed home and couldn’t get drafted. Maybe it was the power they held over him because of his yearning to be with one, just talk with one.’ The conclusion is sanitised but the general idea is clear: women are among the most insulated, hypocritical and clueless members of the civilian population.

Just as troubling is the tendency of the warrior ethos to validate violence by enlisting it in a cult of authentic experience. Claims that everyone secretly loves killing are shaky. Since World War Two, the US military has made a systematic effort to break down the reluctance of recruits to fire their weapons in combat. Boot camp is less a finishing school than a remaking of the self. And the kinds of killing military men learn to do cannot be sublimated into a universal ‘destructive element’, a phrase Conrad intended to refer to human experience in all its tragic dimensions. War is not simply an expression of the beast within. Nor is it merely an opportunity for intense male experiences unavailable in civilian life – physical testing, the creation of community. It is also a product of policy decisions that can be challenged, changed or reversed.

Marlantes doesn’t take on any of this as he trudges towards an unsatisfying conclusion. Hawke is fragged by a grenade meant for Cassidy. Mellas decides that ‘he alone could make Hawke’s death meaningful by choosing what Hawke had chosen, the company.’ He shares a cup of coffee with a militant black soldier named China. The company chants the praises of their fallen comrades, and the clouds cross the moon. The political questions remain: why are these men in that place? Who is responsible? Is this what we want? Until we learn how to ask them more insistently, we will be stuck with the demons of Vietnam, which won’t be exorcised any time soon, and more imperial misadventures are on the way. There it is.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.