For me, drawing is an inquiry, a way of finding out – the first thing that I discover is that I do not know. This is alarming even to the point of momentary panic. Only experience reassures me that this encounter with my own ignorance – with the unknown – is my chosen and particular task, and provided I can make the required effort the rewards may reach the unimaginable. It is as though there is an eye at the end of my pencil, which tries, independently of my personal general-purpose eye, to penetrate a kind of obscuring veil or thickness. To break down this thickness, this deadening opacity, to elicit some particle of clarity or insight, is what I want to do.

The strange thing is that the information I am looking for is, of course, there all the time and as present to one’s naked eye, so to speak, as it ever will be. But to get the essentials down there on my sheet of paper so that I can recover and see again what I have just seen, that is what I have to push towards. What it amounts to is that while drawing I am watching and simultaneously recording myself looking, discovering things that on the one hand are staring me in the face and on the other I have not yet really seen. It is this effort ‘to clarify’ that makes drawing particularly useful and it is in this way that I assimilate experience and find new ground.

This practice is rooted in my experience of drawing from the nude and from nature. But I found it could be moved across surprisingly easily to the elements of abstract painting, centring as it does on inquiry and what happens down there on the paper. I have always believed that those ‘ultimate’ statements of the great protagonists of abstract art were, in fact, declarations of new radical beginnings. Would those principles and geometric forms really yield the riches dreamed of? Or would they prove a block to creative will and passion? But, in art, prohibitions and denials are always a challenge and a powerful spur to inquiry.

For the last 50 years, it has been my belief that as a modern artist you should make a contribution to the art of your time, if only a small one. When I was young, the situation was very different. Abstract painting hung like a mirage in the desert. The door had been pushed open by a small number of visionary artists – mainly Mondrian, Kandinsky, Malevich, Rodchenko. Although travelling by different routes, each had arrived at what was virtually a common core. Having discarded the figure and nature, what remained? Colour as colour itself, those simple shapes and forms that geometry and writing provided, and the material facts.

Severe limitations indeed, but did they hold the secret of a new way of working? No tried or tested criteria existed: everything that would constitute a viable art form had to be found, discovered, reinvented or recreated. It was an immense task but one that seemed essential if the implications and insights of modern art were to be pursued. The very bleakness and constraints of this uncharted land seemed to hold an attractive potential, as Stravinsky claimed in Poetics of Music: ‘My freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit.’

But to be excited by the prospect of a great adventure is one thing, to act is another. To make a start, I had to sacrifice some hard-won achievements and joys. For instance colour, about which I had only recently gained some understanding, now had to be laid aside until an abstract form equal to its purity could be found. You cannot just paint colour: if you try to do this you inevitably end up in the trap of monochrome painting. It was seven years before I found a way of even beginning to work with colour. But first I had to make a start.

Perhaps the time I had spent drawing allowed me to trust the eye at the end of my pencil. Movement in Squares (1961) began in this way. It came at the end of a time of great difficulty for me. I had very nearly lost the studio, and even when I managed to secure it, I had no real sense of what to do there. Although I had taken a few steps in the direction of abstract painting, I had not yet arrived at a point where I could establish a dialogue. One evening on my way to the studio, I thought of drawing a square. Everyone knows what a square looks like and how to make one in geometric terms. It is a monumental, highly conceptualised form: stable and symmetrical, equal angles, equal sides. I drew the first few squares. No discoveries there. Was there anything to be found in a square? But as I drew, things began to change. Quite suddenly something was happening down there on the paper that I had not anticipated. I continued, I went on drawing; I pushed ahead, both intuitively and consciously. The squares began to lose their original form. They were taking on a new pictorial identity. I drew the whole of Movement in Squares without a pause and then, to see more clearly what was there, I painted each alternate space black. When I stepped back, I was surprised and elated by what I saw. The painting Movement in Squares came directly out of this study. My experience of working with the square was to prove crucial. Having been lately becalmed, now a strong wind filled my sails.

The way of working I had found was both new and yet familiar. If my subject had been the human figure instead of a geometric form, I would have been looking for the ways in which the balance shifted. I would have found a twist or turn, which gave life and movement. I chose other geometric forms – the circle, the triangle, the oval, the curve – and found that through drawing I could analyse and study them. What could a triangle, for example, do and, equally important, not do? I put the triangle through its paces. I treated other pictorial elements as units in a similar way. For instance, in 1962, when I tried to introduce a third colour into the Black and White paintings, I soon realised that this was impossible because there was ‘no place’ for a third colour. I had come up against a problem that would in the past have been called ‘plastic’. The structure I was working with was binary and that had to be broken down or opened up if it was going to include a third factor. I did this by ‘pacing grey’, approaching grey simply as a different kind of unit. What is grey? It lies between black and white. It can be a single, central grey, or it can move in steps or modulations of grey.

This fluidity of grey movements and its capacity to bridge the light/dark contrast allowed me to keep a door open for colour. I had to work through the Black and White paintings before I could even begin to think about possibilities of colour. There are no short cuts. I had to go step by step, testing the ground before making a move. It would be a long time before I felt ready to leave the support of the greys for full colour.

Some people thought that I gave up my Black and White structure for a far less radical approach to colour. But this was not the case; the challenge of colour had to be met on its own terms. Just as I had inquired earlier into the square and other geometric forms freed from their conceptual roles, I now felt I had to inquire into colour as another pictorial player – in many ways the least emancipated and possibly the most complex of all.

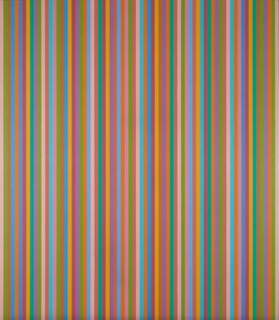

At that time, it seemed to me that form and colour were incompatible, that they destroyed one another. If I wanted to make colour a central issue, I had to give up the complexities of form with which I had been working. In the straight line I had one of the most fundamental forms. The line has direction and length, it lends itself to simple repetition and by its regularity it simultaneously supports and counteracts the fugitive, fleeting character of colour. Although Seurat’s dot is comparable in its simplicity, the line has fractionally more going for it.

My studies of the greys paved the way for the colour movement in Late Morning (1967-68). In that painting, I began in a very simple way to draw with colour. The blue to bright green movement is the form. At the core of colour lies a paradox. It is simultaneously one thing and several things – you can never see colour by itself, it is always affected by other colours. As a child one plays by lying on one’s back and filling one’s sight with the blue of the sky, only to find the blue goes slowly towards grey. Your own eye produced the after-image of yellow-orange to compensate for the intensity of the blue. Colour relationships in painting depend on the interactive character of colour; this is its essential nature. I had given up the complexity of form in my Black and White paintings, but I found that the principles that lay behind them – contrast, harmony, reversal, repetition, movement, rhythm etc – could be recast in colour and with a new freedom.

Although careful never to presume ‘to know’ what the pictorial elements would do in a particular situation, I began to feel that experience was fuelling my inquiry and that, whether I felt prepared to make some advance – or not – I had no choice but to do so. Having twisted my colour round the straight line, I looked again at the curve element and turned it into the supple twists of Song of Orpheus (1978). I drew these curves together into clustered fields spliced by diagonals.

The work became increasingly finely balanced and beyond a certain point needed firmer and more robust treatment. I returned to a broader stripe or band, but the growing complexity of the colour relationships required further changes. It is part of a painter’s work to be aware of the role that distance plays in the viewer’s experience. Ecclesia (1985) seen close up shows a particular group of painted colours. Each band has a clear identity. Step back and the colours begin to interact, further away still a field of closely modulated harmonies cut by strong contrasts opens up. I had to work simultaneously on these two levels: the physical identity of the painted colours and the visual experience of their relationship. I used cut bands of painted paper in a collage technique to adjust, change and move colours around.

This group of stripe paintings turned out to be a rich vein of colour thinking. In the end, that very richness precipitated a new approach. By making the effort to draw, I found my way. I had to lay aside the almost magical interactive power of colour that I had taken to a high level. The stripe itself went too; its limits had been reached. I needed to move the eye in different ways over the canvas.

I searched for a new form that would be unlike any I had used before: a form that did not have the familiar identity of squares, triangles, ovals etc. Eventually, I found what I was looking for in the conjunction of the vertical and the diagonal. This conjunction was the new form. It could be seen as a patch of colour – acting almost like a brush mark. When enlarged, these formal patches became coloured planes that could take up different positions in space. They could serve several functions and being contained they were also movable: could change scale, harmonise or contrast with one another, repeat, echo, ‘create places’ etc. A whole new field of relationships opened up. Together with a more extensive use of my particular collage technique, I had arrived at means broader than any that were available to me before. Now drawing with colour became central to my activity. I found I had to establish a common plane, which ran right through the composition, and from which and to which the spatial advances and recessions of colour would relate. This could not be predetermined – it had to be found afresh each time. It was essential to get across the area, to build a chain of visual events that would carry the eye through its own realm. Shimmered Shade (1990) is one of the paintings that came out of this. I had found this new way of working by taking up an opposing position. It can sometimes happen that, when confronted by what seems to be a wall, which one cannot get either through or round, a kind of radical reorientation is called for. Turning the whole thing over so that an approach can be made from the opposite side, as it were. If this is to succeed, it nearly always means relinquishing some cherished notion or something that you have relied on. This destructive side to creative life is essential to an artist’s survival.

You cannot deal with thought directly outside practice as a painter: ‘doing’ is essential in order to find out what form your thought takes. The ‘new curves’ that I started in 1998 grew directly out of paintings such as Shimmered Shade. The latent visual arcs and sweeping movements came to the fore in Painting with Verticals 1 (2006) and Red with Red 1 (2007). Retaining the diagonals and verticals of the earlier group of paintings, I introduced a curve that connected to the existing structure. This is the underpinning of my new curvilinear work. The vertical is still there, acting like a break in the movement across the canvas. The cut collage pieces define the various contours that arise from combining and recombining the slender curve with its diagonal accents. This has developed into a layering technique that allows me to weave forms and colours together in a supple plastic space. I have reduced the number of colours and increased the scale of the imagery. Would it be possible to once again build up a repertoire of these invented forms, a repertoire that might gradually acquire sufficient momentum to put itself at risk, to precipitate its own kind of hazard? It is only through the experience of working that answers may be discovered within the inner logic of an invented reality such as the art of painting.

All pictures illustrating this article © Bridget Riley.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.