It’s now at last clear that most Labour politicians are sure they’re going to lose the next general election. Some of them are behaving as though they’re already in opposition. Not by criticising actual government policy – they’re too craven for that – but in the more modern way, à la Blair c.1995 and Cameron c. 2005, of calling for a ‘debate’ on their party’s future, preparing the ground for a re-examination of ‘values’, a ‘reinvention’ of the party for a new age. And so it begins. They’ve given up hope, so they talk as if hope is what they’re made of. Last month, James Purnell, who resigned from his job at the Department for Work and Pensions in June, plainly feeling he was meant for higher things, sent a round-robin email to various eminent figures announcing the launch of Open Left, which he described as ‘a three-year project to renew the ideas and thinking of the left through open debate and new policy ideas.’ The project, he explained with due modesty, ‘aims to redefine left-wing politics for the 21st century’. ‘It would be great,’ he added, more disarmingly, ‘if you wanted to get involved.’ Some people did! And their contributions, which take the form of responses to a number of questions – ‘What do you consider made you left-wing?’, ‘How would you describe the sort of society you want Britain to be?’, ‘Which person, event, era or movement from the past should we look to for inspiration now?’ – have started to appear on the new Open Left website, sometimes by way of the Guardian. It’s giddy stuff.

One reason Purnell might be asking these searching questions, apart from wanting to fill the vacuum that is his own head, is that he, and people like him, desperately want to be able to say they’re on the left but genuinely don’t know what they’d have to believe for that to be true. His first question asks, plaintively: ‘What is it about your political beliefs that puts you on the left rather than the right?’ He needs to know, because he’s pissed off that the Tories have ‘stolen’ Labour’s ideas: he evidently wants to be told what makes him special. Later he asks, even more plaintively: ‘Is there anything distinctive about Labour’s goals, if the Conservatives can say they share them?’ He might as well admit that there is no distinction, though he does see some problems with the way things are. ‘We let ourselves think that government worked best when it was publicly owned and centrally run.’ Ah, so that was what New Labour has been getting wrong: it hasn’t been sufficiently receptive to the notion that private enterprise has a role to play in state provision. At least Purnell did his bit to put that right, in his Welfare Reform Bill, which, besides insisting that certain categories of benefits claimants should work for no money, would contract out jobseekers’ services to private companies.

In his quest for a definition of the left, Purnell has settled on a move from equality of opportunity to ‘equality of capability’, a phrase nicked from the work of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. Except that, not having the Aristotle, he doesn’t mean it quite the way they do. The Open Left project is sponsored and overseen by Demos, one of those nifty think-tanks where besuited young people talk about the emerging shape of the 21st century, and Demos, too, has an interest in ‘capabilities’. ‘Personal resources – such as skills, character, health and material resources – deeply affect people’s ability to shape their own lives,’ runs one of its foundational statements. ‘Our programme of work on capabilities will focus on the skills and traits’ – health and material resources clearly being of subsidiary interest – ‘people need to lead a fulfilled and autonomous life.’ Skills, character, health, material resources: spot the odd one out. That’s right, three of them are things people can be helped with. ‘Character’, on the other hand, is about people helping themselves. Purnell may fade away (we live in hope). The danger is that whoever is leading the Labour Party in five or ten years’ time, or whenever it next wins office, will look, and speak, very much as he does.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

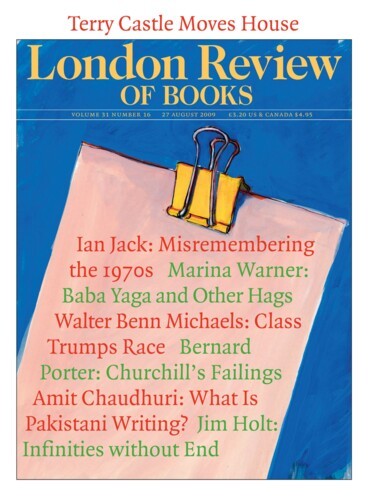

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.