Bound for an airport in the US in the 1950s, Keith Kyle, then the Washington correspondent for the Economist, stopped off at a pharmacy, dashed in, dashed out, hailed a cab and only remembered, an hour or so later at altitude, that he’d left his own car at the store with the engine running. His posthumous memoir, Keith Kyle, Reporting the World, is about the world as he saw it, the many things it threw at him – mostly golden opportunities – and others which, despite his prodigious memory for historical detail, he simply couldn’t recall.* ‘In my ointment,’ he wrote, ‘there exists a fly that at times has loomed Kafka-like threatening to absorb all else … a minor physical malfunction in that part of the brain that deals with short-term memory.’ The book speaks touchingly of this affliction, which began at an early age and was compounded, during his brief attempt at postgraduate research, by ME, an unknown illness half a century ago.

Kyle’s best known work is his history of Suez, published in 1991: he was in his late sixties, with a sterling career as a journalist and several fellowships behind him, by now a senior associate member of St Antony’s and a staff member of Chatham House. His long immersion in international affairs made research a relatively easy task: he assembled his materials in only three years, yet Suez is still regarded as definitive.

Kyle’s undergraduate studies in history at Oxford had been interrupted by the war; he’d served as an infantry captain and returned to take the degree in 1947. He leaped at the chance of research and was happy to serve as secretary of the Union, where he’d already made his mark as a speaker. But the listlessness he’d begun to feel before his finals was now a curtain of mist suspended between his powers of concentration and the archives in the Bodleian. ME forced him to abandon any thought of scholarship and look for less demanding and less solitary work. Before long the BBC took him on as a talks producer for the North American Service (‘that position,’ he writes, ‘had in fact been vacated by Tony Benn’). He worked underground in the broadcasting bunkers dug for the war; ‘in some of the studios the river Fleet could be heard rushing beneath the floorboards.’

In 1953 he was hauled up into the light of day by the Economist. From his posting in Washington he made his way around most of the states during the heyday of McCarthyism, as the civil rights movement was picking up steam. With black community leaders facing a conspiracy charge as a result of the bus boycott in Montgomery, he took off for Alabama, where he was struck by ‘an impressive 26-year-old cleric, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr’. Harangued by the editor of the Montgomery Advertiser about the hypocrisy of the Northern states, Kyle slid in a question about King. The editor looked ‘awestruck’. ‘That,’ he replied, ‘is an authentic intellectual.’

It was the kind of thing Kyle liked to hear about a celebrity, but he was charmed by all sorts and, not long afterwards in Washington, found himself at an Italian Embassy party ‘in danger of drowning in the enormous liquid pools of Sophia Loren’s eyes’. A ‘bitchy marchesa’ did her best to disabuse him: if he’d had any Italian, she confided, he’d know that Loren spoke ‘like a fishwife, what you call Billingsgate; all her films for Italian audiences have to be dubbed.’

On the eve of the Suez crisis, Kyle, a former admirer of the Liberal Party, set up a meeting in Washington with the Tory vice-chairman in charge of candidates, who happened to be in the US. Kyle’s idea was to leapfrog his way to a nomination and return to Britain. He cancelled the appointment as soon as he heard news of the Anglo-French ultimatum and copied his terse cable to Conservative Central Office: ‘In view of the British and French aggression against Egypt at Suez I can see no point in going through with the interview.’ It was the first step on his long journey that led to the Suez history 35 years later.

When he returned to the BBC, as a reporter on the Tonight programme, Kyle became a familiar face in the living-rooms, lounges and increasingly the front parlours of Britain, guiding viewers through the colonial crises in Africa: he filed stories about Mau Mau, the Katanga secession and UDI. By the end of the 1960s he was steering towards more controversial subjects. He had his first proper spat in 1969, after a lightning display of short-term memory. He’d lately been in Beirut where he’d heard a rumour that three El Al planes were to be hijacked or assaulted. One hijacking and an armed attack had already taken place and Kyle was sitting in the green room waiting to go on air with a different story altogether when news of a third incident broke. That must be ‘El Al Three’, he told a colleague. His editor was impressed and had him repeat the assertion in front of a camera. The Israelis, whom he admired, took him for an accessory to the attacks. As a result he lost two big interviews, with Golda Meir and the Israeli foreign minister, Abba Eban.

Shortly afterwards, he filmed the demolition of a Palestinian house in the (newly) Occupied Territories; as part of his voice-over he read out an article from the Geneva Conventions. The Jewish Chronicle called him ‘one of the most extreme pro-Arabists among British journalists’. There was a visit to the BBC’s chairman by the Jewish Board of Deputies, but Kyle’s research was unimpeachable and the charge of ‘pro-Arabism’, or anti-semitism as it would be nowadays, simply failed to stick.

These were minor provocations by comparison with his 1977 report (again for Tonight) on detention in Ulster. The focus of the story was Bernard O’Connor, a high-profile Catholic in his mid-thirties, who had been held by the RUC for seven days and interrogated for 51 hours – he was thought to be organising killings on behalf of the Republicans. Kyle got wind of O’Connor’s treatment in detention just as the attorney general, Sam Silkin, announced an end to the interrogation methods in Ireland that the European Commission of Human Rights had condemned. The O’Connor interview stirred up a gale of invective against the BBC for its ‘bash Britain’ programming. Kyle was summoned by Silkin, whose drift was very clear: Kyle should let O’Connor know that there was a good case against the chief constable of the RUC and that he might want to proceed. It was a civil suit, heard by a Diplock court; O’Connor was not compensated for brain damage but he was awarded ‘exemplary damages by way of punishment of the police’. Kyle was relieved: the judgment vouched for his programme’s accuracy. It also confirmed his earlier worries about detention, expressed in a piece about the BBC’s coverage of Northern Ireland for the Listener in 1971, a few months after internment came into force:

If our political leaders are not perhaps those best equipped to teach us how to report, they can sometimes show us what to avoid. Of the 900 plus arrested under the Special Powers Act in Northern Ireland about half have so far been released. Not one has yet been charged. Speaking on ITN’s News at Ten Lord Carrington, the secretary of state for defence, said: ‘You must remember that the people being questioned are murderers or people indirectly responsible for murder.’

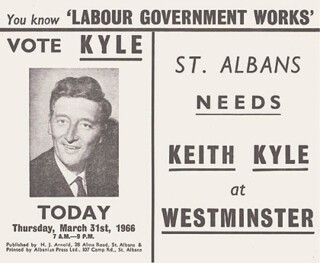

The only disappointment in Kyle’s long career was his failure to win a seat at Westminster. Over Suez, he’d turned down the chance to become a streamed Tory candidate; ten years later, he ran and lost as Labour candidate for St Albans; in 1969 he failed to get selected for Labour in North Islington; in 1974 he lost for Labour in the new constituency of Braintree and again, in 1983, for the SDP in Northampton South, standing for ‘what might be described in anticipation as a Blairite programme’ – in retrospect, one shudders slightly. In the 1980s, Kyle became a valued contributor to the LRB, also enthusiastic about the Social Democrats at the time. Kyle’s piece for the paper in 1981 after a by-election in Croydon foresaw a dazzling future for the SDP/Liberal alliance.

It is now apparent that the public opinion polls were consistently correct in showing that, while support for the Liberal Party as such remained of a traditionally modest order and support for the Social Democrats alone was a similar or even smaller percentage, backing for the two-party alliance as a third force in British politics was a wholly different matter, and promised the chance of a complete breakthrough under the existing electoral system.

The best one can say of a man who moved from Liberal to Tory to Labour to SDP is that his political loyalty was vivacious – in his mind’s eye, Kyle was the life and soul of every party. Yet even without the voters’ endorsement, he could look back over his life with some satisfaction. He had rubbed shoulders with the great, the good and the disreputable; he seemed to know everyone and everything, dead or alive; and now, as a member for nowhere north or south of anywhere, he could at last get started on the book that that would clinch his reputation as a historian.

Many of the better stories in this memoir are not about the laurels bestowed on Kyle, or citations from the glowing reviews of Suez, but anecdotes drawn from a life of rich and hectic contact with other human beings. After the poll in St Albans, 1966: ‘I voted for you,’ a woman in the constituency tells him. ‘As I murmured expressions of gratitude, she went on: “I could never vote for Victor Goodhew. His chain of restaurants all cook with sunflower oil.”’ And best of all a ‘very tragic episode’ in Northampton in 1983:

A civic body had organised a brains trust, with the three candidates taking part. When a question was asked by an elderly gentleman about the Middle East I foresaw for myself a certain advantage through possessing more specialist knowledge than my two rivals. I was called on last and gave what I thought was a balanced and informed reply. Immediately I finished the questioner gave out a short groan and died. He slumped to the floor and was immediately certified dead by a doctor who was present.

Beneath the courtesy and disarray Keith Kyle turned out to have the killer instinct after all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.