after Ovid

Pentheus – man of sorrows, king

of Thebes – despised the gods, and had no time

for blind old men or their prophecies.

‘You’re a fool, Tiresias, and you belong

in the darkness. Now, leave me be!’

‘You might wish, sire, for my affliction soon enough,

if only to save you from witnessing

the rites of Dionysus.

He is near at hand, I feel it now,

and if you fail to honour him – your cousin

the god – you will be torn to a thousand ribbons

left hanging in the trees, your blood

fouling your mother and her sisters.

Your eyes have sight but you are blind.

My eyes are blind but I see the truth . . .’

But before Tiresias had finished with his warning,

even as the king pushed him away,

it had already begun.

He was walking on the earth,

and you could hear the shrieks

of the dancers in the fields, see the people

streaming out of the city, men and women,

young and old, nobles and commoners, climbing

to Cithaeron and the god

who was now made manifest.

Pentheus stared out in disbelief.

‘What lunacy is this? You people

bewitched by cymbals, pipes and trickery –

you who have stood with swords drawn

in the din of battle on the field of war –

now dance with a gaggle of wailing women

waving tambourines? You wear garlands

instead of helmets, hold fennel wands

instead of spears, and all for some boy!

If the walls of Thebes were to fall

– which they will not – it will be

at the hands of soldiers and their engines of war,

not by the flowers, the embroidered robes

and scented hair of this weaponless pretty-boy.

Find him! Bring him here, where he’ll

confess that he’s no son of Zeus and these

sacred rites are just a shaman’s lie.

Bring him here to me now, in chains!’

His counsellors gathered, muttering restraint,

which just inflamed the king who

like a river in spate

boiled and foamed

at any hindrance in the way.

His men returned, stained in blood

and claiming they saw no sign

of Dionysus, just this priest of his

– a comrade and an acolyte – and they

pushed forward the man, a foreigner,

hands tied behind his back.

Eyes bright with rage, Pentheus

spoke slowly:

‘Before you die, I want your name,

your country, and why you came here with this

fraud and his filthy cult.’

Unblinking, the prisoner replied:

‘I am Acoetes, from Lydia,

son of a humble fisherman,

now a fisherman myself.

I learnt how to steer, to set a course,

to read the wind and stars,

so I left the rocks of home and went to sea.

I’d raised a crew, and on our way to Delos

a storm forced a landfall

on the shores of Chios. The next morning

I sent the men to fetch fresh water

and they came back with a child.

The bosun pulled him up on board, saying

they’d found him in a field, this prize,

this boy as beautiful as a girl, stumbling

slightly from sleep, or wine.

I knew, by the face, by every movement,

that this was no mortal,that I was looking at a god.

“Honour this child,” I said to the crew,

“for he is not of us.” And to the boy:

“Show us grace and bless our labours

and grant these men forgiveness,

for they know not what they do.”

One slid down the rigging, calling

“Don’t you bother with prayers on our account,”

and the others circled, nodding and shouting,

their voices fat with greed.

“I am the captain, and I’ll have no

sacrilege aboard this ship, and no

harm to our fellow traveller.”

“Our plunder,” said the worst of them

taking me by the throat

to the cheers and yelps of the rest.

And their noise woke Dionysus – for it was him

who opened his eyes –

“Tell me sailors: what’s happening?

How did I get here and where am I going?”

One told him not to worry, asked him

to name his port of call.

“Naxos. Turn your course for Naxos,

my home, and you’ll find a welcome there.”

And so the mutinous crew

swore by all the gods of the sea they would do

just that and told me to set sail.

Naxos lay to starboard but

winking and laughing

they made me steer to port.

“I’ll have no part of this,” I said,

and I was shouldered from the helm.

“No one is indispensable, captain.

Our safety does not lie with you alone.”

And the painted prow was turned

away from Naxos, out to the open sea.

Then the god began to toy with them.

Gazing out from the curving deck

across the ocean, feigning tears, he cried:

“These are not the shores you promised me,

these shores are not my home.

What glory is there when men

deceive a boy: so many against one?”

My tears were real, but the mutineers

just laughed at both of us and kept on rowing.

Now I swear to you by that god himself

– and there is no god nearer than him –

that this is true: that the ship just stopped.

It stood still on the sea as if in dry dock.

The panicked men pulled harder,

letting out sail to try and find the wind,

but ivy was swarming up the oars

twining tendrils round the blades,

whipping along the decks and up the mast,

dragging at the encumbered sails

till they sagged in heavy-berried clusters.

And now the god revealed himself at last.

Around his brow a garland of grapes;

in his hand a wand, tight-twisted with vine;

and at his feet, the slinking

phantom shapes of wild beasts:

tigers, lynxes, panthers.

Illusions, perhaps, but the crew began to leap

overboard, in terror or madness or both.

One body darkened and went black,

back arcing in a curve; another started to call out

just as his jaws spread wide, his nose hooked over,

his skin hardened into scales. Another, still

fumbling with an oar, looked down

and saw his hands shrinking till they were

hands no more, just fins.

And I watched one, reaching up for a rope, finding

he had no arms

and as he toppled over,

finding he had no legs either:

all torso, he back-flipped into the sea,

tail horned like a crescent moon.

They leapt on every side in showers of spray:

bursting free of the water, plunging down again

like dancers or tumblers at play.

The only human left of twenty

I stood there shaking

till I heard the god speak out:

“Hold your nerve

and this empty ship

and track us down the coast to home!”

And so I did. And there I joined

his rites and sacrifices, and now I follow him:

Iacchus, Bromius, Liber, Dionysus.’

‘Well,’ said Pentheus, ‘I have listened patiently

to this long, rambling fantasy of yours:

an attempt, no doubt, to diminish my anger

and delay your punishment. Well, it didn’t work.

Take him, men, and break him on the rack.

Send him down to Hell.’

And so Acoetes was dragged away

to the cells; but while the fire, the steel,

the instruments of pain, were being prepared

the doors flew open of their own accord

and the chains fell from his hands.

Hearing this – not trusting anyone now –

Pentheus stood and went

to settle things, once and for all.

Alone, he clambered up Cithaeron, the mountain

chosen for these rites, now ringing

with the songs and chants of the maenads,

the celebrants of the god.

And he was stirred by them, roused like a warhorse

at the sound of battle trumpets, their

shiver in the air. The long cries

thrilling through him

he pressed on:

skittish, fevered, feeling again

some passion in him flare.

Halfway up the mountainside,

surrounded by woods, was an open clearing.

Here he stood, in full view. Here he looked

upon the naked mysteries with uninitiated eyes.

The first to see him, the first

to rush at him, the first

to hurl her sharpened wand into his side,

was Agave, his mother,

screaming: ‘Come, my sisters, quick!

There is a wild boar here we must kill!’

And the three sisters led the rest

and fell on him in frenzy,

and Pentheus the king was terrified, crying out,

confessing all his sins. Blood

streaming from a hundred wounds

he called to Autonoe: ‘I am Pentheus!

Don’t you know your own nephew?

Would you do to me

what was done to Actaeon, your son?’

But the names meant nothing to her,

and she simply

tore his right arm out of its shoulder.

Her sister, Ino, wrenched off the other

like a chicken’s wing.

With no hands left to pray, no arms

to reach for his mother, he just said,

‘Mother, look at me.’

And Agave looked, and howled, and shook

the hair from her face, and went to him

and took his head in her hands

and in a throb of rapture

twisted it, clean off.

In her bloody grip, the head swung

with its red strings: ‘See,

my sisters: victory!’

And quicker than a winter wind strips

the last leaves from a tree,

so all the others ripped Pentheus to pieces

with their own bare hands.

By this lesson piety was learned,

and due reverence for the great god Dionysus,

for his rites and for this holy mountain shrine.

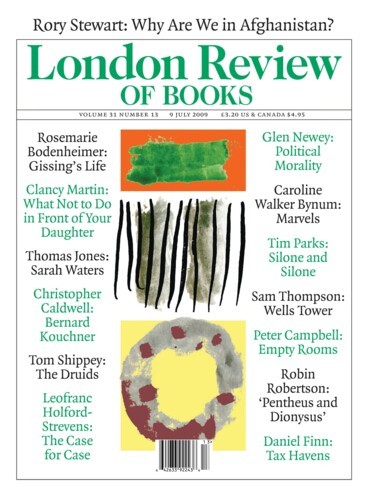

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.