What would you want with that? They said, and fairly,

when the auctioneer’s van dumped it in the drive.

It was far worse than they knew. One absent bidder

had ruined me for the thing, the quartz was cracked

and I’d lied about it being a prototype;

none survived, thanks to the famous flaw

that left them on the seabed with their pilots

smeared all over their one wall. No matter.

This thing still looked straight out of the codex

with its double skin of pig iron and sheet steel,

the daft bespoke of all that brass-and-walnut

and, of course, that eye. Which I avoided.

From the air I must have looked like a dung-beetle

as I wrestled it, all breathers and reverses,

over the hill and into the ring of rocks

I’d laid the day before as anchorage.

What did I want with it? God only knows

there were days when I wondered, sat bored to tears

with my legs asleep, my hands on the dead levers

and barely light to read the empty log,

but something – it was maybe just the cost –

had me stay on, and so I kept my station

till such goose-cries or gear-grinds as could reach me

came slowed and lowered as through a dream of water.

Two years into my watch they showed themselves.

Shadows too fast for clouds, too slow for birds;

then a looming black-eyed face I thought

some kid’s, until I saw it had no mouth.

Now work was a pure joy. I tuned and attuned

and saw their shapes darken and clarify

and heard the bell fill up with their long song.

I was happy. I mean: it would have been enough.

It was the morning. I heard a chain lock up

on the roof, the rocks grind under me

and before I understood the meaning of it

we came free, and a great force bore us upward.

How long the raising took I do not know,

but through the weightless orb there rang a song

so vast and strange I thought my head would burst.

My eardrums did. I was so long past caring

that when the quarry clanged under the bowl

where I lay curled, I had to prompt myself

to be bewildered. In that hourless day

my only certainty was that we’d risen.

It took me both my hands to turn the wheel.

Light cut the door; I put my weight to it

and took my small step down into a world

that was identical and wholly other.

When they ask me what I saw, they all expect

some blissed-out excuse for my not saying,

but I know what I saw: I saw in everything

the germ and genius of its own ascent,

the fire of its increase; I saw the earth

put forth the trees, like a woman her dark hair;

I saw the sun’s star and the river’s river,

I saw the whole abundant overflow;

I saw my own mind surge into the world

and close it all inside one human tear;

I saw how every man-made thing will turn

its lonely face up to us like a child’s;

I saw that time is love, and time requires

of everything its full expenditure

that love might be conserved; and then I saw

that love is not what we mean by the word.

For some idea of it, choose a point

in the middle of a waterfall, and stare

for as long as you can stand. Now look around:

you see how every rock and tree flows upwards?

So the whole world blooms continually

within its true and hidden element,

a sea, a beautiful and lucid sea

through which it pilots, rising without end.

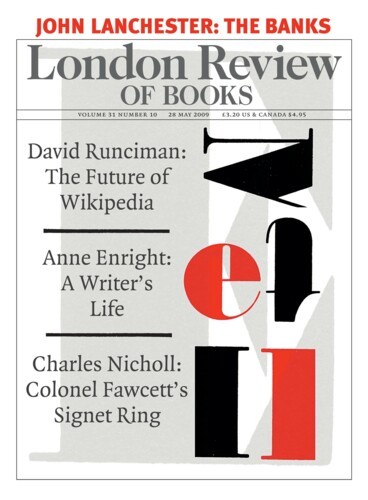

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.