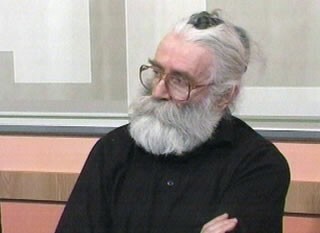

At the time of the parliamentary elections in Serbia earlier this summer, the possibility that Radovan Karadzic, once the leader of the Bosnian Serbs, might be handed over to stand trial at The Hague seemed remote. The acquittal of the former KLA leader Ramush Haradinaj in April had stunned opinion in Serbia and added to the sense that the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia was a Serb-grinding machine which spat out Bosnians, Kosovo Albanians and Croats intact. The idea of any more Serbs going on trial was not popular: even someone like Karadzic, born in Montenegro, long resident in Sarajevo and regarded by many as a ludicrous figure. His arrest late last month illustrates how rapidly things are changing in Serbia, and how keen the new pro-European leadership is to drive its policies forward. The process of EU accession has long been conditional on the delivery of the big three: Karadzic, Goran Hadzic, a Croatian Serb wanted for the massacre of Croats in Vukovar in 1991, and Ratko Mladic, the hands-on commander at Srebrenica. But the capture of Dr Karadzic – psychiatrist, poet, New Age healer, telegenic bigot and mass murderer – is the greater public relations coup.

Four months ago the position of the pro-Europeans in Belgrade looked shaky. In almost every forecast for the 11 May election the nationalist Radical Party (SRS) stood a very good chance of forming a government. A few days before the vote, people in the capital watched the streets fill with Radical supporters, fresh off the buses, heading for a downtown rally, their blue and white banners aloft under lowering skies, their manner aggressive-dejected, ready to make a point: these were thoroughbred Serbs, impoverished and passionate, dressed in standard-issue combats and busy T-shirts.

It was a promising moment for the Radical leader Tomislav Nikolic, deputising for the party’s president, Vojislav Seselj, who flew to The Hague several years ahead of Karadzic and is currently on trial for war crimes. The Radicals were neck and neck in the polls with Boris Tadic’s Democratic Party, which was heading an alliance with a handful of smaller parties ‘for a European Serbia’. The Radicals looked likely to score at least as well as the alliance, and emerge as the senior partner in some kind of coalition.

As the rain drove down on the rally, the Radical crowds retreated under the façades of the buildings, where they sheltered in long, resolute-looking lines, drying off their placards of Seselj and taking a grim pleasure in this minor setback. The image of the party as a redneck monstrosity is oversimplified, but that’s no bad thing, for the SRS itself or for Serbia. It pays to have one of your number pulling an ugly face if you want the EU to extend the hand of friendship a little further. The Radicals are cast as fundamentalists – no time for Europe, plenty for Russia and undying devotion to the idea of Kosovo – but they see advantage everywhere and know how to play off one patron against another. While Dragan Todorovic, a party notable, pleaded at the rally for an ‘economic alternative’ to membership of the EU – full, fraternal co-operation with Russia – Nikolic reminded the crowd that Serbia was ‘part of Europe’, with ‘the EU on our borders’.

Are you with Moscow or Brussels, a man or a girl’s blouse? Or can you be both? These were familiar themes in the election build-up and they’ve persisted. Whoever came to power, it seemed, would want to contrive an enviable dual status for the country a few years from now, cutting manly trade deals with the Russians and spinning around with a curtsy to collect the cheque from the Europeans. Whether they were in government or opposition, the Radicals would be a reminder to Brussels that Serbian nationalism was a force to be reckoned with. Their lingering presence on the political scene – in opposition, as it turns out – is to that extent a national asset.

The election results were a surprise. Even with Kosovo so prominent in the campaign, three months after its proclamation of independence, the Radicals did much less well than expected, with about 29 per cent of the vote, while Tadic had a very good day with about 39. Vojislav Kostunica’s ruling party, the DSS (predicted to be the decisive player in post-election coalition haggling), gave a poor performance, with only 11 per cent of the vote. Kostunica, who has kept Serbia spinning on the spot for the last four years in a blur of ambivalence, will have to reconsider his position. The same goes for Nikolic and the Radicals, whose attempt to form a government with Kostunica’s party and the smaller Socialist Party of Serbia (ex-Milosevic) ended in failure. The SPS were decisive in this; they’d done well enough in the elections to determine which of the two rival blocs would govern. In June, after lengthy negotiations, they walked out on Kostunica and the Radicals and started talks with Tadic’s people. Matters went well and by the end of the month they had come to an agreement. At last there was a government to speak of. Eight weeks had elapsed since the election. The key date in that long interval was 15 June, when Kosovo’s ‘independence’ constitution came into force: another perilous, storm-burst moment after the Kosovan UDI in February. Politicians in Belgrade had clearly decided to retire below decks until the danger had passed, leaving Tadic, in his formal role as president, to signal his disapproval.

On 11 May I was in Gracanica, an isolated enclave of Kosovo Serbs, not far from Pristina. Like the other enclaves and the bigger swathe of Serb-inhabited territory north and west of the Ibar river, Gracanica voted in the Serbian elections. The UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (Unmik) and the Kosovo Albanian government in Pristina were unhappy about the Kosovo Serbs casting votes in local elections under self-supervision, and strongly opposed to their voting in a Serbian general election. There were plenty of Nato troops in town, but everything went off quietly. A Serb in his sixties, a little drunk, approached the huddle of reporters outside the polling station and sounded off against the parties in Belgrade and their representatives in Kosovo: useless, self-serving, liars and thieves. Other voters and polling officials looked on, apparently undismayed. Two hard men slung a racial insult at an Albanian journalist; another told us: ‘Serbs will never recognise an independent Kosovo, but they will accept the realities of living together.’ The old drinker was right in a way: this municipal vote was the first chance in a long time that Kosovo Serbs have had to replace self-appointed spokespeople and minor barons with candidates of their preference: voter turnout was high.

In Kosovo, 15 June was hardly a bright new morning. Russia weighed in at the UN to ensure that Unmik’s departure would be held up for as long as possible. Closer to home, Serb leaders in northern Kosovo announced that they would form their own local assembly. Serbs further south are not sure what this means for them: their homes are not contiguous with Serbia proper, unlike those of the northerners, and it’s not obvious that they share the northern fervour for full separation from Albanians. They live in places Belgrade can’t control and they’re almost certain to comply with the regime in Pristina – the new constitution involves a review of passports, ID cards and vehicle number plates – in order to stay out of trouble.

The Kosovo constitution is hard to fault as a blueprint for a democratic, secular republic; it’s good, too, on the substantial Serbian minority, designating Albanian and Serbian as the two official languages. Like the Romanian constitution, it nods to Nato in a clause about ‘Euro-Atlantic integration’ and pledges Kosovo to ‘a market economy with free competition’. Serbs in Serbia proper are heading in the same direction but they recoil from the constitution of Kosovo: it feels to them like pirate authorisation for a surgical procedure that starts with amputation and ends with a severed limb performing grotesque gestures of its own. For Kosovo Serbs – especially in the north of the territory – there is no mad rush for free markets. They receive substantial bursaries from Belgrade so they can remain in Kosovo flying the flag of Serbian sovereignty: a good proportion live up beyond the provincial border, putting in regular appearances in Kosovo in order to qualify for the handouts (one reason the number of Kosovo Serbs is hard to count). These bursaries, awarded in Serbian dinars, sustain the population of northern Kosovo and the system of patronage which rewards the right kind of loyalty. A miniature command economy, then, with the addition of some high revenue from crime, mostly smuggling.

Serbs in the north of Kosovo have taken 15 June as an occasion to bunker in a little deeper. They are very hostile to the Ahtisaari plan for ‘supervised independence’ – a plan now being implemented under the auspices of the EU and an International Civilian Office backed by 25 countries, including the US, which favour a two-state solution. The plan was drawn up under UN auspices but blocked in the Security Council by Russia. The determination of the ICO and the EU to push it through regardless is not popular with Serbs, especially the Serbs of northern Kosovo, where any attempt to impose law and order – the stated mandate of the EU mission in Kosovo – will be resisted.

At the same time, it’s hard to think of the ‘assembly’ of Kosovo Serbs, which convened at the end of June, as anything more than a symbolic snub to Pristina and an echo-chamber for anti-independence rhetoric. We Serbs, it will be repeated, can never live under Albanian rule. That is surely a kind of truth, at least for the time being, and one that the Ahtisaari plan, which envisages decentralisation to the point of self-rule, is at pains to acknowledge. It will be interesting to see how northern Kosovo Serbs react to the big flows of money that the EU plans for the enclaves in the south.

The nagging worry is that Serbs in the north are trying to turn the partition of Kosovo, which Albanians have always opposed, into a fact on the ground. In the 1990s Serbian intellectuals mooted several schemes for partition and it was rumoured last year that the Serbian government was considering it again, in the run-up to Pristina’s UDI. But even if partition became an acknowledged reality in Kosovo, Serbs would still feel a ‘phantom pain’ from severed parts of the territory below the Ibar – including important Orthodox sites – while objections from Kosovo Albanians would go beyond mere words. For obvious reasons, partition is a worrying prospect to Serbs living in central and southern Kosovo. Redrawing the present border of Kosovo, whether one believes it to be a provincial or a national boundary, would extend the legacy of the Milosevic era, when ‘territorial’ integrity and ethnic integrity were both invoked – first one, then the other – to hasten disintegration.

‘The UN had no reason to come down on one side,’ said Gerard Gallucci, Unmik’s man in the Mitrovica region. The Ibar runs east-west through the town of Mitrovica, dividing Albanians in the south from Serbs in the north. Gallucci’s offices lie on the south bank, but he is on good terms with many Kosovo Serbs. An American with a background in the State Department, he is not popular with Albanians because he persists in repeating, stubbornly and clearly, that you cannot have a satisfactory multi-ethnic compromise if you’ve already settled on an outcome that’s unacceptable to one ethnicity. Gallucci believes that Milosevic made intervention inevitable. What could and should have been avoided was the implicit promise to Albanians, post-intervention, that there would be full independence notwithstanding Resolution 1244, which said nothing of the kind. Separation from Serbia was a foregone conclusion, he believes, the day the Americans began building Camp Bondsteel, the enormous military base south of Pristina; the Serbs had no incentive to discuss the new arrangement once they knew that key decisions were out of their hands.

In Gallucci’s view, then, intervention was fine, even though it was non-negotiable (the Rambouillet conference, just prior to the bombing, was a declaration of war by the West, not a negotiation). Independence, however, is not fine precisely because it’s not been negotiated. That’s a stubborn nut for Serbs to crack, but there’s probably a kernel of principle. Gallucci is, by instinct and from his time in the State Department, deeply suspicious of Washington – another reason Kosovo Albanians don’t care for him – and when he says the UN ‘doesn’t work for one group of countries’, he means that in Kosovo he’d rather it hadn’t. We met while there was still no government in Belgrade, but Gallucci felt that even with a Tadic coalition in power – which is now the case – northern Kosovo might be ungovernable from Pristina, let alone from Brussels. Whatever their misgivings about the UN, Kosovo Serbs had come to regard it, he said, ‘as their shield’, and for that reason Unmik should probably remain in place, even if it was often ‘corrupt and undemocratic’ men in northern Mitrovica who were being shielded. No one south of the Ibar has any patience with this kind of reasoning. Gallucci is one of the first items of UN furniture the EU mission will want to see shipped out of Kosovo, if he hasn’t gone already.

A two-minute walk into northern Mitrovica brings you to the office of Oliver Ivanovic. Ivanovic is in his early fifties, a businessman but increasingly a political animal waiting for a proper career in politics – he’s currently a free-floating, high-profile advocate of peaceful coexistence for Serbs and Albanians. When Nato entered Kosovo in 1999 he became a member of the ‘bridge-watchers’, a Serbian vigilante group. They are still a presence at the northern end of the bridge that spans the river and divides the two communities, and serve as a salutary reminder that for all the dangers of intervention, non-intervention would almost certainly have cost more lives. The bridge-watchers nowadays are little more than ageing skinheads, bumming off Belgrade and assaulting stray Albanians: anaemic descendants of the Milosevic-era extremists, who were fully armed and better financed. Ivanovic got out of bridge-watching a while ago and recast himself as a Mitrovica moderate, willing to do business with people in Pristina, including Albanian politicians. He headed a Serbian list for elections to the Kosovo parliament in 2004 and even though the seats it took were never occupied, harder men in Mitrovica felt that he shouldn’t have stood in the first place. He received the usual threats and in 2005 his car was blown up. He is the acceptable face of northern Mitrovica and all visitors to Kosovo, from NGOs through party political delegates to journalists, are directed to his door.

Some forty countries have recognised Kosovo’s independence, but it’s noticeable that the further north you get from Pristina, beginning in Gerard Gallucci’s offices, the more resistance there is to the idea. Ivanovic, for example, will tell you that even if two-thirds of the UN’s member states were to recognise Kosovo, it would change nothing in international law. Kosovo Albanians, he says, have been far too fixated on ‘status’ – i.e. the drive for independence – and according to Ivanovic this fixation is ‘a sign of weakness’, by which he means Kosovo’s failure to make headway on economic development and flourishing public institutions: the so-called ‘standards’ devised by the internationals for the territory in 2003. ‘Standards’ were seen as stage one of a two-stage model: assure the foundations of a Western-style, market democracy, open a dialogue with Belgrade and guarantee freedom of movement in the territory; then, and only then, resolve the question of status.

Everyone agrees the first stage has been bypassed, largely because of a chicken-and-egg argument, Kosovo Albanians insisting with some justification that the vagueness of the territory’s status was undermining their ability to meet the ‘standards’. Preferring irresolution to independence, Serbs took the opposite position; to which Ivanovic adds a note of disdain for people seeking new national boundaries in a world where nation-states, he thinks, are obsolete. He would like Kosovo to be left hanging as ‘an incomplete national project’, one of two open-ended stories, the other being Serbia. He imagines a return to the task of ‘standards’ – investment, an economy, jobs and services, law and order – and, before long, an EU start-up package of such generosity for both entities that questions of national and territorial identity simply melt away. In other words, he would like Kosovo to remain a part of Serbia, perhaps for the good reason that any other position would not be a vote-winner in Kosovo Serbian areas.

The Centre for Civil Society Development is an NGO with premises in a guarded compound deeper into Mitrovica north. Its co-ordinator, Momcilo Arlov, operates across the Serb-Albanian faultline in more conspicuous ways than the suave Ivanovic and faces higher risks. One wall of his office still bears the traces of a recent grenade attack and there’s a bullet hole in the window. The men who run Mitrovica are against ‘dialogue’. Arlov and his colleagues work mostly with younger people. In the rundown Serbian-language schools and faculties, they’ve invited them to consider the curriculum and debate its contents with their teachers; they’ve revived student union activity, encouraged school councils and parent-teacher associations; they’ve taken part in demonstrations in Mitrovica – against Kosovo’s UDI, for instance, to which Arlov is thoroughly opposed – and urged young Kosovo Serbs to distance themselves from the violence favoured by the old guard. Eighty per cent of their projects are run in conjunction with Albanian NGOs. That is as good as, if not better than, anything managed by Unmik, the EU, the Kosovo government and the swarm of foreign charities in Kosovo.

Arlov is a troubled activist, and the Mitrovica factor is to blame. He is constantly threatened by his Serbian elders for fumbling towards a modus vivendi with Albanians. His frustration with the old guard is probably surpassed by his disappointment with Kosovo Albanians for failing to reciprocate. They are the winners in the conflict, he feels, and should now create the conditions in which he, and others like him on the losing side, can act as brokers between the two communities without putting their lives at risk. Until now the Kosovo government has shirked the business of creating wealth and jobs, and offering Serbs a way into a depoliticised, de-ethnicised economy.

Up in Serbia proper, there is no shortage of NGOs. The catchwords (including ‘capacity-building’ and ‘advocacy training’) tell you where you are; so does the list of donors. Youth Initiative for Human Rights, for example, is funded by several of the Western embassies in the Balkans, two UN agencies, George Soros, the Organisation for Security and Co-Operation in Europe and the Swedish Helsinki Committee for Human Rights. Young people in Serbia who pin their colours to the mast of liberal democracy have something in common with the dissidents of the Cold War era. The sense of a clear divide between East and West, reinforced by the Nato intervention of 1999, is reminiscent of the Cold War template and still shapes the way people in Serbia think, or feel they ought to think, eight years after Milosevic’s fall.

The ‘ought to’ factor is a result of the bombing, which has made it hard for young activists, whose values might be more or less ‘Western’ in character, to identify wholeheartedly with the US and Britain. Andrej Nosov, who runs the Youth Initiative offices in Belgrade, is even cautious about the great dream of the EU. Nosov detects in Boris Tadic what he calls a ‘Gastarbeiter mentality: “Let’s go to Europe to get money and eat butter.”’ Prosperity alone, he feels, may not sweep away the residue of Serbian ultra-nationalism, though the arrest of Karadzic will have raised his spirits.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Radical Party’s preference for friendship with Russia is driven largely by suspicions of an aggressive, condescending Europe (and behind it Washington), yet conservative nationalists can be neither as anti-Western nor as pro-Russian as they would like to be. Ljiljana Smajlovic, the editor of the powerful Belgrade daily Politika – once a party organ, then a Milosevic fiefdom, now part-owned by the German media corporation WAZ – called Europe an ‘ontological ideal’: ‘It’s where we feel we belong. In Communist times we were pro-Western and even Milosevic believed he could be reconciled with the West.’ She approves of the relationship with Moscow, but feels that links with Russia tend to be a liability for politicians in Belgrade; the election results in May don’t contradict her.

For all sides, there are practical considerations. Nosov’s ideal of a human rights culture emerging from the Milosevic years without being promoted or bankrolled from the outside has not been possible and, though he has occasionally refused USAID money, he knows that reliance on European and American funding leaves groups like his open to the charge that their product is an unwelcome foreign import. Nevertheless, the fact that influential donors continue to look out for them allows Youth Initiative people and other groups a leeway they wouldn’t have otherwise. In Nis, a couple of hours south-east of Belgrade, a contingent of young fascists, members of Nacionalni Stroj (National Alignment) and other groups, have plagued Nosov’s colleague Maja Stojanovic for months, surrounding the meeting centre she has set up for local youth and threatening her personally. Without a sense of lifelines beyond Serbia, she’d have had to call it a day. Youth Initiative’s slogan ‘I am the heart of Serbia’ – seen most often as a lapel badge with a pictogram heart – has been controversial, in Nis and every other city. The message is that Kosovo, too often referred to as the heart of Serbia, has become a distraction from more pressing realities in the rest of the country. The badges appeared before the elections and they’re still being worn.

The Radicals, for their part, haven’t been able to wallow undisturbed in dreams of a reconstituted Serbian nationalism. They have worked carefully to widen their support and have built up the party as a business with a core of satisfied clients. When they talk about cleaning up politics in Serbia, it pays to remember that the leadership was once closely associated with Milosevic and the gilded age of corruption. In the last few years, they’ve used local government strongholds to cultivate a class of small entrepreneurs with a dislike of building regulations, commercial laws and tax of any description. In Zemun, a district of Belgrade, the Radicals waived construction permits, issued trading licences like confetti and added a layer of energetic hustling to a part of town that was already stacked with organised crime. (The leaders of the Zemun clan, shot while resisting arrest, were suspected of planning the assassination of Zoran Djindjic in 2003.)

The Radicals have dealt cleverly with outsiders. In political terms they can still look frightening: there is the skinhead following, the mawkish talk of a Greater Serbia and the fact that they are still led by Seselj: a so-called ‘chetnik’ who has denied his links to the SRS-affiliated paramilitaries known as the ‘White Eagles’ – Vocin massacre (Croatia, 1991); Visegrad massacre (Bosnia, 1992) – and continues to rail against his prosecutors at The Hague, where he was indicted in 2003 (full proceedings began at the end of last year).

Slobodan Brkic, a staffer at the International Finance Corporation (part of the World Bank Group), told me he thought Nikolic, Seselj’s deputy, had been groomed ‘to look like someone’s boring uncle’, a party caretaker with a realistic grasp of economic issues. Ten days before the vote he promised the Financial Times he would not ‘jeopardise foreign direct investment’ and said that in the event of forming a government, he would appoint economic advisers without a history of corruption, to compensate for the party’s lack of expertise in economics (or possibly for their expertise in corruption – it wasn’t clear).

At any rate the signals were good; the FT reported that ‘foreign companies operating in Serbia say they have pondered a Radical victory and are not anxious about it.’ Nikolic skilfully spun his objections to the controversial Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the EU – fundamental objections about Europe’s support for an independent Kosovo – by claiming that it was only Tadic & Co. who’d approved it, not ‘the citizens of Serbia’. That the same citizens went on to vote in such large numbers for the DS must have come as a shock.

The DS itself is suddenly a party of change embarking on a programme that seems less controversial by the day. Its energetically pro-EU agenda, announced last month, includes full membership in five years’ time plus continued integration into Nato. Brussels has rewarded Serbia by pretending for a moment that its noisy opposition to Kosovo’s independence is not an obstacle to membership and, post-Karadzic, an avalanche of goodwill from the higher reaches of the EU looks likely. Something unsavoury in the eyes of DS supporters – and their former alliance partners – attaches to the new rapprochement with the socialists. Milosevic’s old party is still associated with his programme of Serbian ascendancy in Yugoslavia and tarnished by its former links to his wife’s party, Yugoslav Left, alongside which the SPS fought an election in the 1990s. The socialists were successful war profiteers as well as warriors, engaged in top-dollar sanctions-busting, smuggling, political assassination and paramilitary levies. As Misha Glenny explains in McMafia,* nationalism was a sound business proposition as much as an ideology. The presence of the SPS in government has jogged a few memories about how well it once did.

Russia’s role in all this is less inflected. A supportive arm is slipped around a beleaguered little friend; investment opportunities are picked up when the price seems right; Kosovo becomes a rallying-point for all those who regard the West, with its crusading double standards, as a dangerous enemy. Even if they have reservations about value for money, Serbs welcome investment from an ally that shares the rhetoric about Kosovo. When he was still prime minister earlier this year, Kostunica thanked Putin, during discussions of a big oil infrastructure deal, for his ‘stance against secession’, as if the two things were indistinguishable. Perhaps they are. In any case Russia’s expansionist energy policy has rumbled forward on the debris of an old territorial dispute, with the purchase of a controlling stake in Serbia’s state-owned petroleum processor, NIS, for a painless 400 million euros plus 500 million promised in investment over five years. In 2003 the Russian company Lukoil bought up Serbia’s fuel distributor Beopetrol and made a similar investment pledge but, on reflection, decided not to commit new money. Serbia may or may not get a stake in Russia’s South Stream pipeline when it’s completed in 2013, but it will certainly get cheap energy, like every other amenable client.

Serbs are flattered by the attentions of Europe and Russia, but not dazzled. Until very recently, bet-spreading was something of a Serbian tradition: Miroslav Miskovic, the tycoon who made his fortune out of sanctions-busting in the 1990s, was said to be funding at least two parties in the run-up to the last elections. Yet if voting patterns are anything to go by, people prefer the promise of Europe to the solidarity of Russia. Both come at a price and, as the slightly Euro-critical Slobodan Brkic argues, the Russians dither a good deal less than Western Europeans when it comes to converting money invested into political influence. Younger Serbs hunger for hassle-free visas, travel, the rebirth of cosmopolitanism: these things count more for them than a Russian company acquiring a stake in a bus factory. It’s nonetheless a stretch to imagine Europe and Russia as purely contradictory forces. Many who applauded Fiat’s commitment of 700 million euros to the old Zastava plant in Kragujevac earlier this year saw a bonus in the fact that a lot of cars rolling off the production line would be destined for the Russian market.

Ljiljana Smajlovic told me that the nation is divided from top to bottom on the great political issues of the day, a view briskly countered by Brkic, who argues that ‘polarisation’ is reserved, increasingly, for political elites. Brkic’s Serbia is a place where all kinds of contradictions have emerged – ‘not just young versus old, but rural versus urban, entrepreneurs versus proletariat’ – in the course of a jagged transition, making support for political campaign issues even more provisional than it usually is. If he is right, then what people really think about Kosovo is not clear. When politicians use the K-word, it can sound like a collection box being rattled angrily to keep foreign well-wishers up to the mark. In the broader national imagination, Kosovo is the name of a memory, to do with pride, humiliation, ‘roots’, the richness of Orthodox Christian tradition, a thought with no precise object, and all the more powerful for that. Even so, the rumour rippling through the congregation, this side of the iconostasis, is that Kosovo is no longer the heart of Serbia, if it ever was.

Something Brkic said in Belgrade took me by surprise. He’d remained in the city throughout the bombardment of 1999. He got used to it and came, in those 78 days, to believe the targeting was indeed conceived to minimise loss of life. ‘There were mistakes,’ he added, ‘and the people responsible should rot in hell.’ The figures for deaths and injuries on all sides were contested at the time and remain so. Nato’s early estimates of Kosovo Albanian deaths at the hands of Serbs were pure mendacity; Milosevic’s count of Serbian casualties inflicted by Nato was less absurd and much of that absurdity, according to Brkic, was wishful thinking: once there was no going back, the president had hoped for a thoroughgoing slaughter, to replenish the wells of Serbian nationalism and prolong his hold on power.

On the way down to Nis from Belgrade, I tried for the fifth or sixth time since the bombing, when I’d stood in the mountains of northern Albania with the rest of the media watching refugees coming out of Kosovo, to draw up something like a death count. People who favoured intervention (as I did) and those who opposed it tend to count the dead in ways that suit them. The numbers still seem to matter for the record, not the argument. The ICRC has good data for the ‘missing’ in Kosovo: there are currently about two thousand, the great majority Albanian, of whom 351 are known to have died. Their names are recorded in a book, which exists in print and online and is now in a fourth edition: Paul-Henri Arni, the delegation chief, and his colleagues in Belgrade and Pristina keep track of cases closed, often through DNA matching of remains with living relatives. These missing combine with the number of dead established promptly and beyond doubt on the Kosovo Albanian side at around half the estimated 10,000 on which the State Department, the ICTY and Human Rights Watch appear to agree. On the Serbian side, there is a helpful incident report, listing (mostly) civilian deaths and drawn up by the fiercely anti-interventionist International Action Center in New York: the total comes in at around 550, to which at least the same number should be added for ‘war-related’ deaths caused by injury and illnesses, including cancer. (Thousands of civilians who suffered serious injury but have not died are another matter. Then there are those who were killed by Kosovo Albanians after Nato entered the territory.)

Nevenka Deljanin, a war widow in Nis, had a record of military deaths in Serbia, which she kept on a shelf in the living-room of her little flat: an official memorial volume put out after the bombing, with photographs and details of all servicemen, police, reservists and volunteers lost in the war for Kosovo, Nevenka’s relatives among them. The total comes to 1002, but the start of hostilities is given as February 1998, more than a year before Nato launched the first missile attack: Milosevic was deploying all kinds of killers and enforcers in Kosovo in 1998 and they were taking casualties at the hands of the KLA, though far fewer than they inflicted on the population at large.

Nevenka had seen a cluster container fall from the sky on 7 May 1999. She was visiting her mother near the hospital in Nis – the damage here and in the central marketplace was pretty bad. She’d had the presence of mind to fling her four-year-old nephew into a ditch in the garden, but she lost her cousin, her brother and her husband in the devastation. The family were not allowed to inscribe ‘death by cluster bomb’ on the graves as they’d wanted and she’d had a terrible time trying to finalise the paperwork for burial; to file her insurance claim, she was asked to estimate ‘the damage in dinars’. She hated Milosevic, but Nato ran him a close second. ‘We never understood why they were doing this to us,’ she said. At least 15 died in Nis on that day and 60 were wounded. It was one of dozens of sorties over the town. Humanitarian interventionists were able to live with this kind of eventuality. When Wesley Clark fielded questions about the attack on a passenger train crossing the Grdelica gorge on 12 April 1999 – one of Brkic’s ‘rot in hell’ moments – he used the words ‘regret’ and ‘unfortunate’; an ambulance orderly from nearby Leskovac who tried to describe it to me felt quite differently.

In terms of human life, the costliest blunders of the Nato air extravaganza were the killings of scores of Kosovo Albanian fugitives, the very people the organisation was sent to liberate, on the Djakova-Decani road in April 1999 and a refugee camp near Korisa a month later. Even the worst incidents involving Serbian civilians fell short of the death tolls in both these episodes and, though Kosovo Albanians rarely complained about it, the bombing was harder in the province than anywhere else. In many ways, Kosovo’s endemic disadvantage has lingered on. Serbian war damage has been tackled with some thought; Pristina by contrast is a manic building site without a foreman, while the villages where people once lived are still empty. The ecological harm done in Serbia – depleted uranium pollution, water-table contamination, chemical leakage and the threat to the Danube and Sava rivers – has been treated as a priority. In Kosovo, by contrast, there are still people prepared to risk their lives by taking a mallet to an unexploded cluster bomblet in the hope of a few euros on the scrap metal market. Despite objections from Russian investors – the state-owned Gazprom among them – Serbia is gearing up to meet EU environmental standards. Kosovo is a pollution black spot with no plans to reduce its carbon emissions.

Other evidence tells the same story. Serbia has two suitors in the form of the West and Russia, Kosovo only one. Serbia is a sovereign state with a piece missing; nearly ten years after intervention, Kosovo’s status is in contention. Serbia enjoys economic growth – between five and seven per cent. It has plentiful agriculture in a world where food prices are spiralling, reasonable energy prospects and 80 per cent of its people in work. The situation in Kosovo doesn’t bear comparison. If Kosovo were really the heart of Serbia, the patient would have been in the mortuary by now. Sooner or later Tadic and his new prime minister, or their successors, will acknowledge that Serbia can get along without Kosovo. Kosovo Albanians will be delighted: no distance from the memory of Serbian domination is far enough for them. Their home will be a heritage site for older generations of Serbs on tour buses, as Ahtisaari proposes, while the youth of Belgrade will prefer to head west. If Kosovo is lucky, it will play host to a thriving Serbian minority that lives by the rules. Both Serbia and Kosovo will see increasing prosperity, which will in turn displace the bitterness of the last thirty years. If Glenny is right, accession to the EU will reduce organised crime in both places. Kosovo will begin producing food and continue lobbying rich countries to take its unskilled migrant labour, while Serbia will attract foreign investment in manufacture, property, banking and eventually agriculture. There will be broad agreement about the two things it’s easy for Serbs and Kosovo Albanians to agree on: the ills of Communism and the virtue of markets. Charming nationalist analogies will lose their currency – torn-out hearts, severed body parts, raw bones of contention, cradles of one thing or another. That is the plan.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.