In the fall of 2002, in the company of a dog named Charlie Chaplin and an architect named Michael Meredith, I set out to drive a 1960 Chevy Apache 10 pick-up truck, at 45 mph, from far west Texas to New York City: 2364 miles through desert, suburbs, forests, lake-spattered plains, mountains, farmland, more suburbs and the Holland Tunnel. I got to know both of my travelling companions during a brief period living in the town of Marfa, Texas, which is also where I found the truck, parked in front of the post office: boxy, banged up, covered in sky-blue house paint, the half-smashed windshield a lattice of stars and linear cracks, like a flag. A Mexican man in his sixties walked outside with his mail and drove it away. Then I found it parked out by the cemetery. Jesse Santesteban, the owner, showed me where he’d signed the engine compartment like an artist, and said I could take a closer look. The doors had handmade wooden armrests, and the seatbelts were fashioned of canvas and chain link. An orange shag carpet covered the floorboards. I offered him $1200 cash. He handed over a green plastic keychain that read ‘Laugh, live, love and be happy!’ and warned: ‘Don’t take it over 45 or it’ll throw a rod.’ A friend later explained: ‘That’s a polite way of saying the engine will explode.’

Having to drive slow, pleasingly to my mind, made fun of the two main preoccupations of my country: velocity and ease. Not that I didn’t appreciate velocity myself. On a road trip a few years before I’d tried to set a car’s cruise control at 140 (mph). Now I would piss off and get passed by everyone, including a guy hauling hay and a wide-load trailer pulling a house. I almost passed a school bus in Arkansas, but when the sleepy driver spotted me, he floored it. I would be the slowest person in America.

Marfa is surrounded by one of the few untouched landscapes remaining in the lower 48 – a high desert formed in the Permian period and left more or less alone since. All roads out of town lead across empty yellow grasslands, through blue sage and cactus-covered mountains, where the traveller’s only company is the weather. A hailstorm once blackened the sky behind me, caught up, dented my hood, starred my windshield, and moved on into the distance. At night the stars glowed like phosphorescence in the sea and were as abundant as static on a broken TV.

At 9 a.m. on a Wednesday, I honked the horn in front of a small adobe where Michael had spent the night with some friends. It was a clear sound in the dry desert air. Michael had left Marfa for Canada but flew back for the drive. On the phone we’d planned the trip as follows: always take back roads, eat only in non-chains, never hurry, spend a day in San Antonio meeting a man I’ll call Don Harris, for whom Michael might design a house, write songs to perform at an open mike in Nashville. Charlie would ride in the bed of the truck, and we would have the cab. I tied his long leash to the truck’s roll bar, so he’d know not to jump out.

Michael dressed like an architect: thick glasses, black pants and a white shirt, the two colours separated by a belt with a brushed steel buckle. He’d met Charlie, but this was his first look at the truck.

‘Hello Charles,’ he said to Charlie, then remarked: ‘I like the shotgun rack.’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘It’s also good for keeping umbrellas.’

He stared. ‘No, man. Umbrellas? What kind of wuss-ass keeps umbrellas in his shotgun rack?’

Before I could answer he noticed the stick shift.

‘I didn’t sleep all night because I was worried about that. I can’t drive stick.’

‘What?’

‘I didn’t think it would be a stick shift. It’s American. Everything’s easy in America.’

‘It’s from 1960.’

I figured I could teach him. There was nothing to hit out in the desert. Then he told me we had to be in San Antonio by 9 a.m. the next day to meet Don, his potential client. San Antonio was just under 400 miles away. I’d planned to reach Del Rio, half the distance, following the Rio Grande.

‘You know we can only go 45.’

‘What? C’mon – you’re joking, right?’

‘No. Really. Look at this thing,’ I said. Michael took in the ancient interior and medieval seatbelts. ‘Can you call and tell him we’ll get there around noon?’

‘I only have his email. I just told him we’d be there.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘we’ll keep driving.’

We were, I later discovered, driving our way through a book I hadn’t read at the time: John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, wherein the author and his dog, Charley, lit out on the back roads of America in the fall of 1960, in a new GM pickup, in order to ‘rediscover this monster land’. Steinbeck is precise and prescient about America, observing that ‘there will come a time when we can no longer afford our wastefulness – chemical wastes in the rivers, metal wastes everywhere, and atomic wastes buried deep in the earth or sunk in the sea.’ In a letter he wrote to Adlai Stevenson, he declares: ‘If I wanted to destroy a nation, I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick.’

But there was no such musing as we made our way east: I was too absorbed in correcting the steering, an act of constant attention. Around lunchtime we’d barely made it a hundred miles. We stopped outside the town of Marathon.

A lean old man touched his cowboy hat, pointed at the truck, and said: ‘’65?’ Michael replied, ‘Yep,’ and the man walked away.

I said: ‘It’s a ’60, actually.’

Michael said: ‘Yeah, but why bother correcting him? He just wants to feel like he knows something – now he feels good.’

We were on a slight downhill: a good place to learn stick, so I let Michael drive. The truck got going after a few stalls, and we rolled through the Chihuahuan Desert. He struggled with the loose steering, veering into the oncoming lane – me scared and hollering, ‘Watch out!’; him apologising, ‘Sorry, sorry, I got a trick leg!’ – until a rank of orange plastic drums, like buoys in the sea of the desert, shunted us to the side of the road. Two border patrol agents asked where we were going.

In this context, Michael in his architect’s uniform and me in a skateboard sweatshirt and Kangol cap, I imagined we made no sense as anything other than a gay couple. They walked off to confer, and seemed to be snickering. Eventually they waved us on. Michael threw it in reverse, and we started rolling back towards Marfa. The agents didn’t bother hiding their laughter.

Then Michael stalled. Charlie lost his balance, fell over in the bed, and gave me an aggrieved look. Shortly afterwards he tried to dive out of the back. I jumped from the cab and somehow caught him before he could hang himself on his leash. He lifted his nose and gave me a gentle tap on the neck. I sat him between Michael and me, and took the wheel.

Charlie was a Catahoula, the state dog of Louisiana, which looks like a spotted wolf, a dingo or, as a man who spotted him on the street once put it, ‘one of those wild dogs of Africa’. He was conversational and made a lot of noises that definitely weren’t barking, growling, or anything canine: ‘Wroarowlwolf.’ ‘Oohwar.’ ‘Rrolf.’ ‘Aaahlh!’ ‘Meol.’ ‘Wrrp.’ Going by all the distinct letters I heard him pronounce (a talent he shared with Steinbeck’s Charley), I was pretty sure I could have taught him to speak a few words in English.

The landscape unfolded, changing only because the light was changing. The truck’s bench seat had springs that poked most of the way through on the driver’s side, and the result of a couple of hours sitting on it was searing pain. Adding to the discomfort, Charlie kept subtly shoving me, until my arm was fully extended to reach the Bakelite knob on top of the gear stick, my left hip pressed into the door, and he was at the wheel.

Michael broke his silence and said: ‘I found out a couple of days ago I’m one of the six finalists to design a memorial for the victims of the attack on the Pentagon.’

It took me a second to realise what he was talking about. ‘What? The 9/11 memorial in Washington?’

‘Yeah. Right where the plane crashed.’

‘Wow. What’s your design?’

‘It’s a viewing pedestal. The people who come to remember are the memorial. They’re living statues. The idea is to be really small and intimate next to something that is out-of-control big – one of the few man-made objects you can see from outer space. For a memorial it seems better to be modest – it’s more likely to be built if it isn’t expensive. I have to meet with them next week in DC. And the New York victims’ families, too. The New York families also want the New York names in DC. Of course the DC names aren’t going to be in New York.’

This struck me as an insult to grief. ‘When do you have to meet the families?’ ‘Uh.’ Long pause. ‘Tuesday.’

I told Michael it was impossible.

‘Let’s just keep driving,’ he said.

Signs of civilisation had begun to appear along the road, indicating our emergence from the landscape of the Palaeozoic and into 21st-century America. A strange tension had been set up, and it would pull at us for the rest of the trip.

At around midnight we arrived in San Antonio and found a motel right beneath I-37. I noticed there was a back entrance, checked in, and while Michael took our stuff inside, I walked Charlie around the neighbourhood, then through the back, catching the door before it closed behind a woman in a grey business suit. Charlie followed me and sat like a gentleman. She gave him a look of withering contempt.

Had she mistaken Charlie for another, very similar looking, Texas Catahoula, named Smut, then notorious in certain parts of the state for swimming in George Bush’s pool, and, when Vladimir Putin came to visit, per the Dallas Morning News, ‘barking and chasing after the president and his visitors’? (The paper also quoted the Westerfields, Bush’s neighbours and Smut’s owners. Mrs Westerfield said: ‘He chased those Russian dignitaries all over that place.’ Noting that they’d eventually castrated the dog, Mr Westerfield lamented: ‘That old boy lost everything because he wouldn’t stay off the president’s place.’)

We met Don Harris the next morning in the lobby of the Menger Hotel, which was pillared, balconied, sconce-and-stained-glass-lit Victorian. Don, a middle-aged man in the midst of all this distinctiveness, was nondescript. He had a rounded physique that seemed to make the light fall away from him. Michael said hello and introduced me as a writer. Formalities concluded, Don asked if he could tell us a bit about the city, then delivered a monologue that was, to me, a coastal American, a total revelation about the history, depth and texture at the heart of the country. He said:

San Antonio has always seemed to me to be a city out of a Borges story, particularly one with knife-fighters, political thugs and Hispanic-Irish gangsters, like Death and the Compass. The past here is so intense that it’s also the present, and nothing ever really disappears. The city’s always existed with wild Indians, soldiers, priests, vaqueros, pachucos, socialites, aristocrats, writers and working people, in a constant mix. Conrad’s favourite writer, R.B. Cunninghame Graham, the Scottish laird – the real king of Scotland, some say – spent several years in San Antonio, attempting to become a cattle baron, going broke, and then, out of desperation, beginning his writing career with an account of a hanging in Cotulla for the San Antonio Express. Stephen Crane wandered around with the Chili Queens in the same plaza where the Comanches would ride into town and receive tribute – pay or the town would be burned and looted. This lobby is the setting for a scene from All the Pretty Horses. John Grady Cole spies on his mother, sitting with ‘boots crossed one over the other’ (I know El Cormac is being reappraised here and there – but he’s still bulletproof in Texas). The Gunter – another cattle king hotel – is where Robert Johnson made his first recordings, in 1936, and rock and roll was born. Eisenhower had an office in town, and he was in it on the morning he heard about Pearl Harbor. I don’t even think he was a general then. The San Antonio gangster Freddie Carrasco, while in prison at Huntsville, made a suit of armour in the style of Ned Kelly and tried to shoot his way out. This is what I mean when I mention Borges.

Then a brisk walk outside. A few quick turns, and we dodged inside a bar where three gamblers were playing cards for money. A drunk shouted ‘Dammit!’ and lurched at nondescript Don, who wove and kept walking towards a glimmer of sunlight at the back. It was a very long bar, terminating at a balcony overlooking the San Antonio River. We stepped out onto it and Don hooked a thumb behind us. ‘The Esquire Bar, the lost state of Esquire. Claimed to be one of the longest bars in Texas. Kind of place that people have their booths in. Completely democratic crowd, too, in the social sense: criminal lawyers and their clients, thugs and socialites.’

Later I looked the place up and found the following customer reviews on Citysearch: ‘Pros: cheap drinks. Cons: staff, bathrooms, local Hispanics.’ And: ‘Only nefarious locals go here. Not recommended for northerners or passers-by.’

Don showed us the courthouse, ‘machine-gunned one morning during the early 1970s in a ferocious drug war that came to a head with a federal judge’s assassination by Woody Harrelson’s dad’. Then he placed San Antonio in continental context, taking us to the edge of a sleepy square and declaiming: ‘Travis Park, in my view, is where Latin America begins. Everything north of this park, in governance and culture, is English; everything south, all the way to Cape Horn, is Spanish. It’s the actual border of the two Americas.’

‘Who is he?’ I asked Michael over brisket and white bread at Black’s BBQ in Lockhart, 72 miles later.

‘I don’t know. He’s just this guy who wrote me and said he wanted to build a house. I don’t know!’

I do know now. He had said that he ‘used to live in the Paradise Valley in Montana with my literary friends Richard Ford and Thomas McGuane’. Some weeks later, I met Richard Ford at a wedding, and I asked him about Harris. Ford squinted and said: ‘Don Harris . . . Don Harris . . .’ Then he raised his hands and shouted: ‘Don Harris is a fugitive from justice! He fled the country to Mexico. I was giving a reading in South Carolina when someone said there was a friend of mine who wanted me to go outside and see him. I said, “Tell him to come in here,” but they said he wouldn’t. I asked his name and they told me “Estebán de Jesús” and I went outside and it was Don. If he’s back in the US now and using his own name he must have resolved his legal troubles. But I’ll tell you this . . . don’t let your friend build a house for Don Harris!’

We woke up the next morning in Crockett, Texas, so far behind Michael’s schedule there was no way we could make the coast without blowing the engine. Our sad room was of the sort Steinbeck, feeling sorry for himself, described as ‘dirty yellow, the curtains like the underskirts of a slattern’.

I walked Charlie across a leach field from the L of our hotel, over to a pawnshop (it shared a single prefab building with a feed store), where cheap, sun-bleached acoustic guitars hung in the window.

‘Michael,’ I said when I got back. ‘Let’s buy a guitar so we can work out a routine for Nashville.’

He replied, distractedly: ‘OK, yeah.’

We made for Louisiana, swaying along an empty road that threaded through trees, interrupted by the houses of the poor. I let Michael drive. Entering Shreveport, he ran just-turned-red after just-turned-red, to avoid stopping/stalling. We swung onto a road north towards Arkansas. Surrounded by Louisiana farmland, we pulled over. This was Charlie’s chance to know his native soil. He sniffed around. Michael’s phone rang. The Pentagon finalists had just been announced that morning in Washington. A reporter from the Albany Times Union, the paper Michael had delivered as a boy, wanted to interview him. He talked as I drove. Then, in Arkansas, we stopped at a gas station, selling unbranded gas, to fill up and get snacks. A thin, beautifully sulky woman in a housedress, right out of a WPA photograph, was sweeping the concrete around the pumps. Her twin sister was at the register, talking lazily with a sexy blonde in a tube top. ‘Can you recommend a healthy snack?’ I asked, trying to flirt. There was a long pause till the counter-working twin replied, in an accent of such deep Arkansan exoticness, a subtle inflection making it clear how unfascinating she found me: ‘How ’bout some peanut butter and crackers?’

As we pulled out of the station Michael said: ‘They were like sirens.’

Half an hour later, I realised: ‘Damn, we forgot to buy a guitar for Nashville!’

‘We’ll just a capella it and get booed off stage – with a lot of thigh slappin’ and hooting!’ Michael declared.

This was what I’d imagined, why I’d wanted him to come along. We made up a Yankee ballad about southern food and southern accents – how we couldn’t resist either one. Title: ‘I Got the South in My Mouth!’ It was a beautiful day for a drive. Sunny. Breeze full of birds. Singing, our voices were bad and scratchy. We were both starting to get colds. As the day progressed we filled the Apache with loaded Kleenex and cough-drop wrappers: a major divergence from Steinbeck, who filled his truck with ‘bourbon, scotch, gin, vermouth, vodka, a medium good brandy, aged applejack and a case of beer’, lamenting that ‘if there had been room . . . I would have packed the WPA Guides to the States, all 48 volumes of them.’ Steinbeck could have spent a lot less time getting lost, then depressed, then drunk.

We had pie for dinner (having skipped lunch), after which I silently drove, and drove, and drove, and drove, the strain on the engine and the torque of our incompatible needs seeming sure to cause some sort of explosion, till we rounded a corner in a blank part of the map near the Mississippi border, where a strip of river and two gas stations, nothing you could call a town, had nonetheless caused two groups of young men to come into proximity – one shirtless and black and drinking beer, the other shirtless and white and selling Confederate flag patches and 9/11 keepsakes. We filled the tank at a station frequented exclusively by black customers, and looked across a dirt road at a station frequented exclusively by white people. The heavy sound of insects was all around, while harsh stares came from the white gas station at the two Yankees and their wild dog of Africa. Then the whites started to shout at the blacks. When the word ‘Fuck!’ rang out, we fled. No more back roads that night. We made for the interstate.

Coming out of the midnight darkness of St Francis County, Arkansas, we took I-40 towards the Mississippi River – while endless trucks did the same thing. Twenty miles from the bridge we broke into a column that stretched back as far as we could see. (Turning around, Michael said: ‘They just keep going for ever.’) This was the only single-lane section of I-40 coast to coast. Usually it’s single lane for just a mile. But that night construction had the highway down to half capacity for more like twenty. The lane was tight, the looseness of the Apache’s steering magnified by the sensation of driving in a trench; I slowed down to 40, 35, 30, to keep from crashing into guardrails or roadworkers. Soon we were holding back a flood of trucks. Space opened up in front of us. By mid-span on the Hernando de Soto, the bridge that carries I-40 into Memphis, we had nothing but open road ahead, while in our wake so many drivers had hit their brakes that the sky was red. I looked in the rear-view mirror and saw a screaming trucker. At the same moment he blew his air horn, and contorted his face in rage. A wrathful BWOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOLF! sound filled my ears and seemed like it was coming straight out of his mouth.

Exiting the highway in Lakeland, Tennessee, Michael said: ‘That was terrifying. I thought we were going to die.’ It was a too close encounter with American velocity: the terror of stopping all these trucks from hurtling along at 80, loaded with consumer goods, all the things we need to make life easy.

After checking into a big Super 8 overlooking the highway, I walked Charlie along something called Huff Puff Road, dropped him in the room then went to check the truck’s engine (sweating oil). When I returned Michael was watching TV, Charlie was drinking out of the toilet, and an ad for ‘Snoop Dogg’s Girls Gone Wild’ came on. Snoop screwed up his face and framed his gold jewellery-covered chest with his arms; teenagers on streets and beaches flashed their breasts at him. It was mesmerising. When the ad was over a feeling of loneliness crushed us to sleep.

At Michael’s insistence we spent the whole next day on the interstate, needle at 45, occasionally 50, steady rain falling. A pool formed in the dents on the hood. We got to Nashville in five hours, ate, and kept going, not even mentioning our plans for the open mike. Hoping to relieve the spring-induced pain in my thigh, I let Michael drive till he almost crashed. Pain or terror: those were my choices. Steinbeck called the interstate a ‘wide gash’ where the minimum speed ‘was greater than any I had previously driven’: ‘When we get these thruways across the whole country . . . it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.’

By nightfall in Knoxville I was done. We exited into a deserted downtown. ‘This is it,’ I said. ‘I can’t take any more of this. You want to get there on time, just rent a car.’

‘Shit, man. No,’ Michael said. We hadn’t talked for hours. ‘We have to do this together.’

‘What? Sit silently in terror? This thing won’t go any faster.’ Michael was silent. Unable to think of anything else to say, I came out with: ‘And that’s such an architect’s belt buckle.’

Then I got out of the truck with Charlie and walked off.

When I got back Michael said: ‘OK. I’ll get a car. But I don’t want the trip to end like this. Let’s drive as far as we can tonight. I’ll get a rental tomorrow.’

What followed was the best drive of the trip. Michael took the wheel, and I looked out the window: a hundred miles of empty road following a low ridge line, like a levee through the woods, nothing but trees with slashes of cloud-filtered moonlight coming through their leaves, and shreds of silver river visible beyond their bare trunks.

We ended up in Kingsport, improbably large for a fume-choked industrial city nobody’s ever heard of. We checked into an Econo Lodge. Michael went to the room and I took Charlie for a walk. I half-noticed something catching the street light in the wet grass, and let go of Charlie’s leash so he could investigate. Suddenly he was lying on his back and rolling on it. He dug in. Legs straight up in the air, head kicked back, Charlie twisted side to side, ecstatic, his eyes pure white. I’d never seen him so fulfilled. I laughed. Here was his inner Smut. When he got up I saw what looked like a rack of thick rib bones with a flap of white chamois on top: a dead animal that had gone flat and sunk into the earth. Then the smell hit me – hard.

Michael and I said goodbye early the next day. I wished him luck with his memorial. He wished me luck with the rest of the trip, patted ‘Charles’ and said: ‘Good call on the belt buckle. I’m gonna get rid of it.’

I carried on in what smelled like a coffin. On a brief stretch of unavoidable interstate, Michael passed us in a tiny silver car, honked, and waved. Then Charlie and I disappeared into the rainy closeness of Virginia and West Virginia, following Route 460, where the two states traded places every few miles. I went to a pizza place, ordered a salad, and the dark-skinned proprietor brought me fresh feta, olives, lettuce, peppers, bread – the homemade meal I’d been wanting the whole trip. I asked him where he was from, and he told me Egypt.

I drove 17 hours without a rest, crossing the Mason-Dixon line at 1 a.m., at the same time as an Amish buggy with reflective bands Velcroed around its horses’ ankles; a quick sleep in Harrisburg, PA, where, beside the banks of the Susquehanna River, hoping to remove the spring that had been boring into my pelvis, I disembowelled the bench seat with a pocket knife; past the Hershey chocolate factory, over towards the Jersey border; across the deep-carved bed of the Delaware River on a gleaming steel bridge, barely wide enough for the truck; another highway gash, and finally we saw the New York skyline. My dog said: ‘Wroarowlwolf!’

Michael didn’t win the contest to design the 9/11 memorial in Washington. He told me they could ‘obviously see through my criticism of the massive war machine’. He’s now teaching at Harvard, and has a dog of his own. Charlie died of cancer in 2004. I still have the truck. It cheers up everyone who sees it in New York (especially firemen). I’ve recently been thinking of driving it back to Texas with my family, a reverse trip that, with two small children and $5 gas, would mock ease even more than velocity.

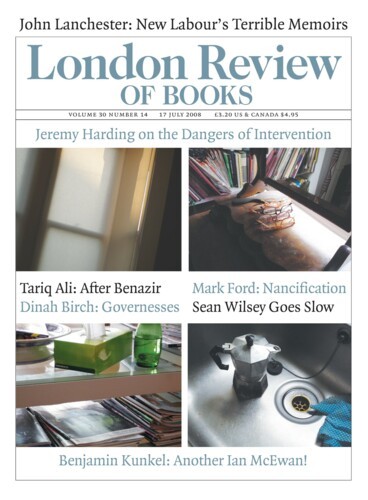

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.