I took a look around Harrods last weekend. Barging my way in through a crowd of animal rights protesters, I wondered if I should tell them to try their luck around the corner. Harrods is selling the furs, but I’d just come from Christie’s in South Kensington, and there I’d been surrounded by the people who buy them.

They buy art, too. A lot of it, for a lot of money. They’re spending most of it on modern art – Old Masters don’t come up for sale very often – and, increasingly, on ‘postwar and contemporary art’ in particular. You wouldn’t want to press too hard on the periodisation: there’s a loose sense that ‘contemporary’ art began in the 1960s, when Pop finally put paid to Modernism, but the proliferation and recirculation of styles in the last sixty years has made the chronology messy. Anyway the market knows what it likes and, for the moment, likes what it sees. Christie’s sold £459 million worth of postwar and contemporary art in the first half of last year. In May, Sotheby’s in New York more than doubled the record price for a contemporary work when it sold Rothko’s White Centre (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose) for $72.8 million; the following night, at Christie’s, Warhol’s Green Car Crash (Green Burning Car I) went for $71.7 million in a sale that fetched a record total of $384 million.

I was in South Kensington to take a look at what would be on offer a few days later at the first big Christie’s sale of 2008. Viewings like this are a nice city secret: free admittance to room after room of modern classics, some of which can be seen only for these few days as they slip from one private collection into another. It isn’t like being in a regular gallery; there’s something different about the kind of attention being paid to the pictures. A man leans in to inspect a detail on a Cy Twombly, looks at the price (estimate: £1.5 to 2 million), then whips a tape measure out of his pocket. One woman in furs tells another that she’s given the children a budget of £10 million: ‘They chose lots of Warhol.’ (I think it’s a game.) A gaggle of off-duty waitresses – they’d been serving champagne – gather around Lucio Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, Attesa, a six-foot-high bright red canvas with a metre-long vertical slit down its middle. ‘Do you think anyone’s noticed it’s damaged?’ one of them asks. The question isn’t silly. When you come across one of Fontana’s works from the turn of the 1960s in the Tate, it’s possible to see it as a decisive intervention in 20th-century art, witty, violent and heroic all at once; severed from that context, and with a caption estimating its value at between three and five million pounds, it’s easy to imagine that the canvas might have been shivved by an outraged passer-by. The year before last, the casino owner Steve Wynn put his right elbow through Picasso’s Le Rêve, which he’d just agreed to sell privately for $139 million. Perhaps he didn’t want to sell it after all.

When the auction came around on 6 February, the Fontana sold for closer to £7 million, the highest price ever paid for one of his paintings. It’s an elegant thing to look at, but there are others just as beautiful for a tenth of the price. Whoever bought it was buying a bit of art history too: the tear in Fontana’s canvas retains the aura of the gesture that made it. To people who care about contemporary art the importance of that gesture isn’t in question. Concetto Spaziale should be a solid investment, its value immune to fashion. How its value is translated into a price is, of course, a different matter. Last year’s record sales were just one more excess in an art market that has been booming for years. Contemporary art made gains of 55 per cent in the year leading up to June 2007. There is nothing to prevent a painting being treated as a commodity: bid a few million over the phone for a masterpiece half a world away, put it in storage then sell it again a year later for a few million more. You wouldn’t even have to look at it, still less trouble yourself with whether or not you were putting the right price on the sublime. You just need to be sure that the price will keep rising.

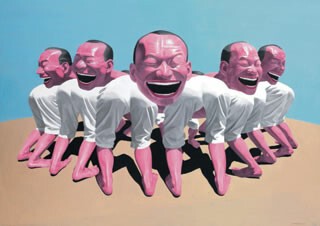

In fact, most of the buyers aren’t behaving this way. Everybody likes to have nice things to put on their walls; it’s just that the rich will pay more for them. But they don’t like to make bad investments. The most expensive painting ever sold at auction is Picasso’s Garçon à la pipe of 1905, which went for $104 million at Sotheby’s in New York in 2004. One hundred million dollars, but not a billion; £7 million for Fontana, but not 50 million. The limit is determined, as with all commodities, by the buyer’s confidence – in this case that he will get something more than merely decorative for his money. That said, if you’re desperate to own a Picasso, you might also be prepared to pay what it takes and write off the loss. A better indicator of market confidence might be the record sums being spent on less proven artists, on Jeff Koons, Richard Prince and Damien Hirst. No one can be sure, yet, how their reputations will fare. They’re risky investments, and should their moment pass, you might find yourself stuck with something you can’t sell but don’t want in the house. Currently, the most speculative money is being spent on contemporary Chinese painting: at the Christie’s sale there was a raw-meat coloured portrait of Mao by Yan Pei-Ming, a sadistic burst of fleshy pinks and reds from Yang Shaobin, and a sinister, denatured self-portrait (see left) by Yue Minjun, the most fashionable of them all. ‘It would be worth taking a few hits on that stuff,’ I heard a dealer mutter to his assistant, ‘just to break into the Chinese market.’

At Christie’s in St James’s for the auction itself, there was little sign of the nerves that are supposed to have seized the market at the end of last year. Confidence is dropping, the analysts say, in the wake of the credit crunch. Yet the estimates were higher than ever, masterpieces by Gerhard Richter and Francis Bacon were on offer (‘estimates on request’) and the saleroom was full to bursting. There’s an enforced indignity to the occasion, expensive coats thrown over the backs of cheap chairs, no discernible hierarchy between bidders and dealers and journalists and hangers-on, all of us squashed together in the marketplace. The auctioneer sees and hears everything. Bids are relayed by smiles, nods and shakes of the head from assistants on phones; they reach him from neighbouring rooms and invisibly from the rows in front. The sales are brisk, unfussy; it would be unseemly to draw attention to the sums involved, to hurry or cajole, at least without charm. ‘Not yours, sir,’ he soothes, ‘the bid’s with me … take your time … will you give me one point six?’ He responds to each change in the bidding with a shift in posture – a lean on the elbows, a flick of the wrist, the extension of an arm, the raise of an eyebrow, each movement more pronounced than the last – and relaxes again only when he brings the hammer down for a sale. There is a constant low hubbub that fades only for the big money. ‘I’ll start at 20 million,’ he announces quietly to open the bidding for Bacon’s Triptych 1974-77, the last of the paintings Bacon made in the wake of the suicide of his lover, George Dyer, in 1971. It hangs there, unlooked at: all eyes are scanning for the bidders. But there isn’t time; it’s over in a flash; the Bacon is sold – to a man in the doorway on a mobile phone, who escapes seconds later – for £26.3 million, the most expensive work of art ever sold at Christie’s in London.

And yet, it seemed to me, the crowd went away quieter than they’d arrived. On those overheated evenings in New York last May, 90 per cent of the lots on offer were sold; at Christie’s this week, it was a back-to-normal 69 per cent. Nothing sold wildly above its estimated price, and so the excitement of seeing money spent without restraint wasn’t to be had. It will have been noted that the pictures doing exceptionally well were by Bacon, Fontana, Twombly and Yves Klein. The hideous Chinese pictures aside, things were less encouraging for the fashionable artists, and therefore for the market as a whole. One of Damien Hirst’s paintings didn’t sell, the other – Sarcosine Antihydride, an array of 1056 dots of gloss household paint on white canvas – just made it. Christie’s probably thought it was a good idea to hang it alongside another spot-painting, Bridget Riley’s Static 2 from 1966, but they won’t make that mistake again. Both paintings have your eyes wandering over their surface, but Static 2 makes you feel like the subject in an experiment of its own devising, while Hirst’s dolly-mixture colours just leave you feeling stupefied. Riley was given a lower estimate than Hirst, but sold for nearly twice as much.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.