Misha Vainberg, like a twisted 21st-century Whitman, contains multitudes. Son of the 1238th richest man in Russia. Graduate of Accidental College in the American Midwest, with a degree in multicultural studies. Victim of a botched circumcision at the hands of Hasidim in New York. A 325-pound behemoth with a fondness for grilled sturgeon and fried chicken wings. Possessor of a ‘toxic hump’ that floods his body alternately with sadness and rage. A ‘holy fool’, ‘an innocent surrounded by schemers’, a ‘modest person bent on privacy and lonely sadness’, a ‘giant florid hymie with big, squishy hands and a rather mean-looking overbite’, a ‘sophisticate and a melancholic’. He pops Ativan by the handful and swills Johnny Walker Black; an aficionado of hip-hop, he rolls with a manservant called Timofey in a Land Rover driven by a Chechen. Dressed in a vintage Puma tracksuit he resembles ‘the infamous North Korean playboy Kim Jong Il’; swaddled in a Hyatt Hotel robe he feels ‘like the Reichstag must have felt when it was being draped by Christo’. Squalid, horrifying and attractive, Misha is meant to embody the excesses and contradictions of our millennial stew of sexual confusion, ethnic tension, appalling consumerism and multicultural angst. You need a poster-sized Venn diagram to keep track of his entanglements, from New York to St Petersburg to the fictional former Soviet republic that gives the novel its name.

Gary Shteyngart would seem well placed to attempt an ambitious satire of the post-Cold War world in all its bloody ethnic feuds, byzantine oil politics and Western narcissism. He emigrated to America from Leningrad in 1979 at the age of seven. In the early 1990s he attended Oberlin, a liberal arts college in Ohio; like thousands of liberal-minded young Americans he landed in Prague in the mid-1990s, an experience that fuelled his first novel, The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. In 1999 he revisited St Petersburg and found Russia even sadder and stranger than the Communist superpower of his youth. In recent years, the New Yorker and Travel and Leisure have allowed him to wander around the world on an expense account and take notes, a great many of which, it seems, have found their way into Abusrdistan.

Any attempt at summarising the novel’s madcap plot seems not only, well, absurd, but almost beside the point. Nonetheless: it is mid-2001. Misha is in St Petersburg, prevented from returning to New York because his Russian gangster father has murdered an American businessman. The US consulate has rejected his visa application nine times. He dreams of New York mainly because his lover Rouenna – a sassy Latina homegirl he met in a Lower Manhattan ‘titty bar’, and who believes Dickens is a porn star – lives in the Bronx. When Misha’s father is himself murdered by a corrupt business associate, all seems lost. No father, no visa, no point in going on; until he is given $35 million in exchange for his father’s business assets. When a police chief happens to mention that a Belgian passport can be obtained from a corrupt consular official in Absurdistan, Misha catches a plane and lands right in the middle of an erupting ethnic conflict.

American reviewers have been unable to resist comparing Shteyngart’s book with John Kennedy Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces, though the two novels share very little beyond an omnivorous, obese hero who falls for a girl from the Bronx. Temperamentally, Misha Vainberg is Ignatius Reilly’s opposite. Reilly railed against the lack of ‘theology and geometry’ in the world, and was repulsed by both modernity and sex; Misha, by contrast, is a sensualist and libertine, hip to the latest developments in music and fashion, and utterly lacking the renunciatory impulse that made Reilly not only funny but touching too, and a little bit sad. Misha is many things, but he is never an occasion for pathos. This may be a consequence of Shteyngart’s indiscriminate joke-making.

Almost nothing escapes Shteyngart’s satirical guns. He takes aim at American military contractors and their effect on the countries in which they operate: ‘Golly Burton, Golly Burton!’ the Absurdi prostitutes ululate as they look for trade, making Dick Cheney’s former company sound like the refrain in a nursery rhyme. A schism between two Christian sects in Absurdistan is traced back to the tilt of Christ’s footrest in depictions of the crucifixion (upward to the left, Svani; to the right, Sevo); the disagreement led to the Three Hundred Year War of the Footrest Secession. Misha’s father is frequently described as having been a Jewish dissident during the Soviet era; it turns out he went to prison for capturing and urinating on an anti-semitic dog, an act which inconveniently took place in front of the KGB office in Leningrad. In Absurdistan’s capital, Svani City, the main street market deals exclusively in used remote-control devices, an excuse for Shteyngart to send up the developing world’s hunger for Western technology. Vladimir Putin is described as looking like ‘a mildly unhappy horse dipping his mouth into a bowl of oats’. Even the Holocaust – and its power as a political and fundraising tool – is a target. Hired as minister of multicultural affairs by the Sevo group responsible for plotting the coup that plunges Absurdistan into chaos, Misha attempts to shake down American Jews with a grant proposal for an Institute for Caspian Holocaust Studies, aka the Museum of Sevo-Jewish Friendship:

Studies have shown that it’s never too early to frighten a child with images of skeletal remains and naked women being chased by dogs across the Polish snow. Holocaust for Kidz will deliver a carefully tailored miasma of fear, rage, impotence and guilt in children as young as ten. Through the magic of Animatronics, Claymation and Jurassic technology, the inane ramblings of underqualified American Hebrew day school teachers on the subject of the Holocaust will be condensed into a concise 40-minute bloodbath. Young participants will leave feeling alienated and profoundly depressed, feelings that will be partly redeemed and partly thwarted by the ice-cream truck awaiting them at the end of the exhibit.

Misha is drawn to the Sevo putsch leaders because they represent the country’s beleagured minority. He believes them to be fighting for freedom and democracy, but it turns out they have the crassest of motives: the oil supposedly in abundance in the bordering Caspian Sea has all been tapped, drying up a bustling trade in kickbacks. So the Absurdis collude with a Halliburton subsidiary for a cut of a support-service contract, to be divvied up when and if the US sends a peacekeeping force (‘How can we make this place more like Bosnia?’ is the question asked by the coup leaders). The Sevo group is in fact in collusion with the ruling Svanis, and a phony bout of civil unrest is staged to draw the world’s attention via CNN and the BBC. Two things go wrong. First, the war gets out of hand, thanks in part to some mercenary Ukrainians sent in to carry out some shelling for the benefit of the cameras. Second, no one in the West cares. Of the Ukrainians, who would once have been proud Red Army soldiers, Misha says: ‘Like any empire in decline, ours was becoming ever more brilliant at knocking things apart, at raising palls of smoke over cratered school yards and charred market stalls.’ This can also be taken as a description of our own flailing American empire and its penchant for heedless destruction. Except that in fictional Absurdistan the country’s dissident leaders actually begged for his city to be attacked. It’s a reminder of the scheming Ahmad Chalabi and his strategic dinners at the White House.

Shteyngart has a gift for physical comedy, and Misha gives him nearly unlimited opportunities. Misha’s body – ‘a continent of flesh’ – is depicted again and again throughout the novel. After his unfortunate circumcision, Misha’s penis is variously described as a ‘crushed purple insect’, an ‘abused iguana’, and ‘a rocket that had failed re-entry’. Hot days make ‘a sour borscht’ of his genitals. His Absurdi lover’s vagina is described as ‘a powerful ethnic muscle scented by bitter melon, the breezes of the local sea, and the sweaty needs of a tiny nation trying to breed itself into a future’. What makes these descriptions more than cheap humour is a certain taxonomic and geographical precision.

Misha is heedless of everything but his own appetites: for food, sex, love, an American visa, a hip-hop life in the Bronx. He has the attention span of a three-year-old. And unless we’re paying close attention ourselves, we may miss the dissonance at the heart of the novel. This man, contrary to the much repeated refrain, is not ‘a sophisticate and a melancholic’. Nor is he a ‘modest person’ bent on ‘lonely sadness’. He is an unholy fool. Only one character in the book even vaguely embodies some more noble ideal. His name is Sakha – a friend of Misha’s, a campaigner for democracy in Absurdistan, and editor of a magazine called Gimme Freedom – and while Misha looks on he is shot in the head during the chaos following the Sevo putsch. Immediately afterwards, Misha consoles himself with internet porn:

As depressed and immobile as a 21st-century Oblomov, I lay on my bed scrolling through the darkest corners of the internet, the laptop whizzing and bleating atop the mound of my stomach. I watched all kinds of unfortunate women being degraded and humiliated, tied up, spat upon, forced to swallow gigantic penises, and I wished I could wipe off their dripping faces, whisk them away to some Minneapolis or Toronto, and teach them to take pleasure in a simple linear life far from their big-dicked tormentors.

This is no doubt meant as one more satirical thrust. A man loses a friend to an undeserved fate; in his grief he turns to images of sexual domination to replace the image of his friend being murdered in the light of day in front of a gleaming Western hotel in a backward ex-Soviet republic. Western technology and sexual imagery as the balm for Caspian grief. Ha ha. Except that, for Misha, it actually works.

The best kind of satire is the kind we’re meant to take seriously. If Shteyngart were serious about Misha, he would make the poor slob pay for his self-absorption. He cannot do this, in part because he cannot see far enough past his own jokes to work out whether Misha is the vehicle or the target of the satire. Is Misha the cynic who can deftly satirise the Holocaust in a grant proposal, or the gullible man-child open to manipulation by people who merely want a chunk of his inheritance? Is he sincere in his love for Rouenna, or for the woman who takes her place, the Sevo beauty Nana who desperately wants him to return to college in New York, and whom he woos by quoting Zagat’s guide to her from memory? And if he is sincere in his love for both – or if they are both merely stand-ins for his love of New York – then shouldn’t this triangle of desire lead him to some moment of realisation?

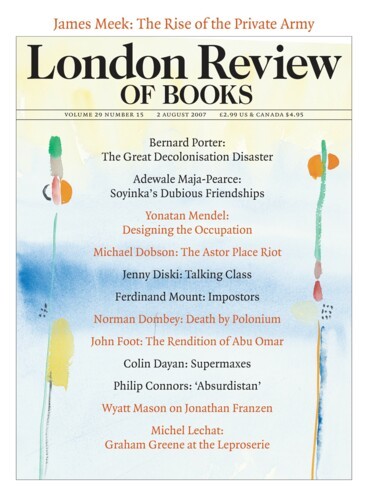

For Misha there are no consequences, ever. He bribes his way out of trouble, or avoids it when he sees it coming. He wants to be a misanthrope but remains a sentimentalist. When a poor woman attempts to peddle her five-year-old daughter for his sexual satisfaction, he claims to want ‘to take vengeance’ – as he puts it – ‘for my life’. His life, not the child’s life. Sure, he claims he wanted to kill the mother. But he didn’t. He’s interested only in ‘the conditions for my salvation’. He rages at the unfairness of the world, but this is disingenuous. Eight pages later he is overcome ‘by a surge of universal man-love’. But he doesn’t mean that, either. He doesn’t mean much of anything he says. Yet his insincerity – the biggest target for satire the novel presents – is never punished. Only ideas and concepts are punished, and punished and punished again: American empire and arrogance, post-Soviet anarchy, silly religious rivalries, Western oil gluttony, inauthentic lifestyle poses, thoughtless acquisition, liberal education. Each of these gets its comeuppance, well deserved and well aimed. Shteyngart even satirises himself in the form of Jerry Shteynfarb (sometimes called, by Misha, Jerry Shitfarb), a former college acquaintance of Misha’s for whom Rouenna falls, a writer and teacher best known for his novel The Russian Arriviste’s Hand Job. This authorial double is described as ‘an upper-middleclass phony who came to the States as a kid and is now playing the professional immigrant game’. Misha, though, is allowed to remain the holy fool – always acted on, never culpable. Fiction – even, and perhaps especially, satire – works its magic on us through the actions of its characters, and the consequences of those actions. Where there are no consequences, there is no magic. Shteyngart remains, at heart, a partisan essayist, happy to ridicule everything in his sight except his fabulous and ultimately hollow central creation.

In an end we ought to have seen coming, Misha abandons his Absurdi girlfriend and takes a train bound for the border, in order to save his own hide. Outside the train, beggars are being shot. Back in Svani City Nana will face an uncertain future. This, of course, does not occur to him. He is too involved in dreams of his own satisfaction, of a life with Rouenna in the Bronx: ‘In our basement, the laundry machines and dryers are spinning. You pass me a rolled-up ball of baby socks, warm to the touch. Our household is large. There will be many cycles. Oh, my sweet endless Rouenna. Have faith in me. On these cruel, fragrant streets, we shall finish the difficult lives we were given.’ We can’t claim we weren’t warned, right up front, in the second paragraph in fact, warned by Misha himself: ‘This is also a book about too much love. It’s a book about being had.’ True for him and true for us.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.