Last year, when she was five, my daughter announced that she was going to become a Muslim.

‘It’s an awful lot of washing,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry, I am able to reach the sink with my feet.’ She went up to her room and stuck six sheets of paper together to make a prayer mat. It was time, I decided, to send her to Catholic Instruction. This is an after-school class that, besides fulfilling her tribal spiritual needs, provides a solid half-hour of free childcare, every Monday. It is conducted by a catechetics expert in lace-up shoes who looks like she means business. When I drove my daughter home after her first class, she was quite unhinged, muttering like an old gossip and quietly raving in the back of the car.

‘I didn’t know he was arrested,’ she said.

‘What? Who?’

‘Jesus,’ she said. ‘I knew they killed him all right. I just didn’t know they arrested him first.’

Hot news. It is still a great story, it seems. Besides, the child has what might be called a religious temperament, being prone to bliss and rendered solemn by the sacred. I used to think that all children were like this, but her brother is a much more pragmatic, ironic sort of guy. He doesn’t believe or disbelieve things as much as look at them to see what they might do next. Even so, there is one tenet he holds dear, and that is the resurrection from the dead of Jesus Christ. He is adamant that there is one living creature who, unlike everyone else who ever lived, did not have to stay dead, once he had died. My son is three. He is on a bad mortality jag. Our summer holiday was spent driving these two young people around Brittany, looking for a toilet and talking about the grave.

I suspect they are in cahoots.

‘Stop at that church!’ says the elder, and, ‘Where are the Romans?’ says the younger, walking with some authority into the medieval gloom.

‘Where is Jesus?’

‘He is on the cross.’

‘Why is he cross?’ and so on.

We do a tour of the dead, the dying, the writhing and the floating. There are six different churches in here, one overlaid on the other. The earliest, painted and carved on the beams of the vaulted ceiling, is a charnel house of dancing skeletons and rows of skulls.

‘Are they dead?’

‘Yes, they are dead.’

My son is completely anxious and completely happy. I look at the roof beams and think, quite inaccurately, that the late medieval mind was very like a three-year-old’s; death was where Europe had got stuck.

It is a common enough idea. It is in the air. I keep stumbling across it: the idea that the clean wind of the Renaissance took with it all our superstitions and our fears. It was there in Brecht’s Galileo at the National, and again in Brenton’s In Extremis at the London Globe, where Abelard’s dialectical method, his ‘Sic et Non’ is pitched against the bonkers fundamentalism of St Bernard of Clairvaux. Here, Brenton seems to imply, is the seed of the modern age. It is one of the founding myths of European secular society that faith succumbs, eventually, to reason. Even though it doesn’t, really.

You can’t be a Muslim, I should say to my daughter – they never went through the Renaissance. Whereas we did, obviously. We Irish schoolteachers, or peasants, or whatever the Enrights used to be: those peasant schoolteachers who aped their Renaissance from the rational British, who got their Renaissance, not from Italy, but by natural right, who got their Renaissance in their father’s womb. Don’t talk to me about the fucking Renaissance, that’s what I say, in a world where the rich think that being sensible is what actually divides them from the poor.

It was spookily prescient of Brenton, though – wasn’t his father a man of the cloth? In September, the Pope came out on Abelard’s side with his remarkable Regensburg speech. ‘For Muslim teaching,’ he said, ‘God is absolutely transcendent. His will is not bound up with any of our categories, even that of rationality.’ Benedict knew exactly where he was pitching his argument in the history of Christian theology, which is to say around 1141 ad, because that’s his job: the Pope likes to think in the long term.

‘It’s your fault, you know. It’s all your fault that Jesus died on the cross,’ I say to my daughter when she is being pious (she is not in the slightest bit good, thank God). I suspect she will stick with it all the way to her Holy Communion: the only girl in Dublin who isn’t in it for the dress.

I can’t tell you how much I hate Catholicism. Though I still like nuns. And I almost miss priests, with their teasing celibacy. All my young life I was subject to sudden and agonisingly profound discussions with strangers dressed in black. I really enjoyed them. One night in the children’s hospital where I was, briefly, a patient, the priest sat by my bed and talked about the small operation I would have the next day; he asked me did I know about the general anaesthetic, and was I afraid I might die. I didn’t think I would die, and I probably told him as much, but I also said that, anyway, I was not afraid of dying, and I remember how keen his interest in me was, just at that moment. After which, we had a very interesting discussion about God. I was, I think, 11.

‘Are you all right there, Father?’ said a passing nurse, airily, and even at 11, I noticed her rudeness and the surge of irritation from the man sitting at my bedside. Twenty-five years later, a former chaplain of the hospital was done for the most vicious child abuse. I don’t know if it was him, though the dates match well enough. I don’t know if priests who are not paedophiles ask children the kind of questions he asked me about death. I want to reach into my past and hold him by both shoulders, and take a good, long look at him.

At 13, I made my last confession, which was just as banal as my first. I think it was the priest’s depression that got to me; the pure irrelevance of him; the fleshy slab of his middle-aged face behind the grille. The world had moved away from this, and I had moved with it, or so it seemed at the time. Three years later I was suddenly, ecstatically Born Again (hallelujah!), because lapsing was not a matter of indifference, after all, but of crisis.

No one talks about how much fun it is to be a fundamentalist. The word has changed, of course: for any rational person, ‘fundamentalist’ now means ‘manifestation of raw evil’, but being a charismatic Christian was a hoot. It was like being at a wild party with no drink, no sex, no hangover, no regrets. I believe! I believe! I am in a suburban sitting-room, and I believe! It was a constant state of expectation and yearning; a suspension so high and long, it was almost like release. Speaking in tongues – I could do it now, if I dared – was pure flow; you had to wince at the sweetness of it. Miracles were two a penny. Everything made sense. People prayed for their lost glasses and found their dentures instead and we all laughed at God’s little joke. You can’t live up there for ever, of course, and the downs, like a junkie’s, were terrible and complicated. The whole group tried to undo the knot of your error, to release you back into the ether where you belonged. These people – dentists, housewives, students, lost souls – performed a kinder and less lonely version of what Catholics call ‘examining your conscience’. This is an overly rational, slightly paranoid activity that involves thinking very hard for a very long time, until the answer comes from somewhere else entirely. Love. God. That which descends. The answer. Bliss.

People like the Pope, who understand religion, also understand that the activity of religion can be highly rational (unless you are a Muslim, according to him). I argued my religious convictions for a year or more, and won every argument (of course) and loved it. Sic et Non! Sic et Non! What conquered my faith in this, its most florid phase, was not the forces of reason, but those of love. It disappeared along with my virginity, I’m afraid. Well not at that precise moment, but somewhere around then, in all the fuss. Virginity. Now there’s a word I don’t get to type that often. I remember not believing in it – quite passionately – I remember saying that there was no such thing; that ‘virginity’ (unlike God) did not exist.

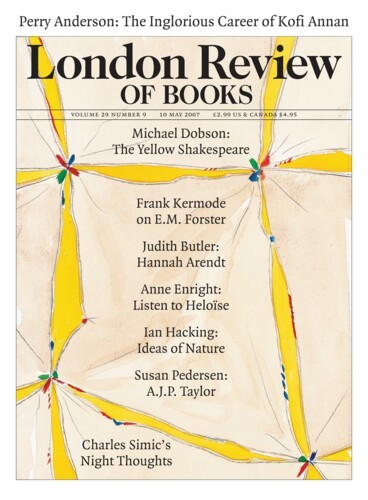

So it is Heloïse we must listen to, not Abelard, or even Bernard. The most damaging thing that happened to Catholicism in Ireland was the legalisation of contraception, because the real religious wars are fought over the bodies of women. Guns are something else again. No one in their right minds, for example, ever thought that Catholics and Protestants were killing each other in Northern Ireland because they couldn’t agree about transubstantiation.

I still believe in God, in some reluctant, furtive part of me. I’m not proud of it. I understand atheists, who are averse to religious people as they might be averse to fat people, as being actually quite dangerous in their weakness. So I am weak (and slightly fat, indeed) and a bit too ethnic, if it comes down to it. I just won’t shape up and become a proper person who believes in nothing at all.

Meanwhile, my daughter is in thrall to the sublime and my son ‘loves Jesus more than Santa Claus’. I have no interest in applying a bracing dose of reason to their credulity: I just don’t feel like pointing out the error of their ways. It is already clear that belief is something they claim as a personal possession, one that they will defend if I try to take it away. This is something akin to sexuality. It is, already, none of my business.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.