Island race or not, we have not been doing at all well when putting out to sea in past weeks. First, in the benign setting of the Caribbean, the vice-captain and muscular icon of the England one-day cricket eleven, Freddie Flintoff, was sacked from the vice-captaincy, though not, for sure, from his iconicity, for having had a great deal too much to drink before driving a pedalo out into the local waters in the middle of the night and then capsizing it; something which I’d have thought was beyond even a man as large and as heavy as Flintoff, so reassuringly stable did pedalos always seem when we far frailer pedallers sat in them. The England players in the World Cup have performed very poorly, and if they have to come home having failed to do anything in the least commendable out on the pitch, then Flintoff’s sottish buffoonery will be the one ranking memory of our participation in that tournament.

That first small piece of faulty seamanship was a farce from beginning to end. The second small piece may not have begun as a farce but it certainly ended as one, when the 15 sailors and marines who had been taken into charge by the Iranians were flamboyantly released, wearing the not too ill-fitting new suits that they had been given, rather as if they too were a sports team setting off on a tour supplied with identical outfits by their sartorial sponsor. This apparently tame climb-down on the part of the Iranians will have come as a disappointment to the tabloid commentators who had been persuading their readers that the holding of these captives, hostages, kidnap victims or whatever was an outrage for which there was no conceivable justification. There were moments when it seemed as if they thought they had lighted on a true casus belli, tied in as the episode was with the incessant, Bush-led demonising of Iran in respect of what may or may not be its eventual nuclear ambitions.

Some of us were unable to see it that way. The notion of an outrage could be based only on the assumption that when the sailors and marines in question were impounded by ‘revolutionary guards’, who can but sound more sinister and politically savvy than a simple able seaman, they were on the Iraqi side of the line held to divide Iraqi from Iranian territorial waters in that part of the Gulf. To start with, we were assured very confidently by this rear-admiral or that that of course they were where they should have been, that it was the Iranian boats, not our own, that had crossed the line and committed an act of piracy. Before too long, the admirals went quiet again, as if no longer quite so sure they’d been reading the charts aright, and if you spend even a short time browsing relevant sites on the internet, you can see why: it’s perfectly clear that, in the opinion of experts of maritime law and international boundaries, there is no agreement as to where Iraqi territorial waters end and Iranian begin. Neither side in this overblown dispute had anything firm to go on.

The Iranians surely knew this, and how refreshing it would have been had our own government recognised from the start what the boundary situation was instead of lapsing mechanically into bluster, a lapse which will have alerted Tehran at once to the likelihood of a simple propaganda victory, leading them on to the eccentric act of magnanimity of taking their temporary British guests round to the local equivalent of M&S and finding suits for them.

As for the behaviour when in custody of the 14 men and – as we were at no point allowed to forget – one woman, what can one say? It was miserable beyond belief. I had always understood that members of the Armed Forces were instructed, should they be captured, to tell their captors their name and service number, and absolutely nothing else. These particular captives appear on the contrary to have fallen in with every demand made of them, admitting trespass, announcing they were being well treated, writing implausible letters home to Iranian dictation and all the rest of it. Little wonder that when they were finally sent back home to this country, they were given demob suits to replace the battle dress they’d been wearing when captured. It’s a pity that they hadn’t had a chance to see the movie reviewed by Michael Wood on another page of this issue of the LRB, in which an outnumbered group of the military stood up a lot more robustly for the West in an earlier clash of civilisations: the Spartans at Thermopylae (the movie version of whose last stand is unlikely to get a showing in contemporary Persia). It would be going a little far to ask that Spartan values be taken as the norm among servicemen and women today but it would be good if they could be brought to realise that to expect to be paid for telling us what their few days of anxiety in Iran were like, in what are laughably called ‘their own words’, is a gross dereliction. As for a government that first gives them permission to take the money and run, and then immediately – and rightly – withdraws it …

Send Letters To:

The Editor

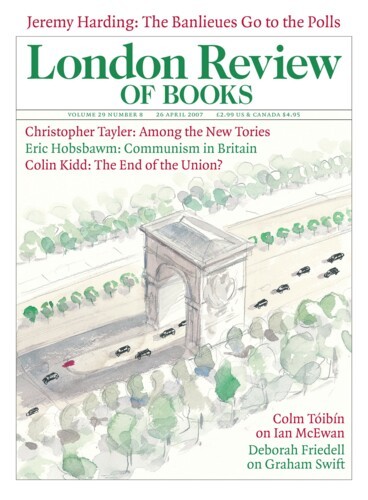

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.