Introduction

Hugo Williams sits looking somewhat

cowed and apprehensive in the tea rooms

of the Waldorf Hotel. His appearance, dark,

formal suit and tie, silk handkerchief

arranged for show in his breast pocket,

makes him look old-fashioned actorish.

It is almost as if he were costumed

for a funeral service, and in a sense he is.

Old theatrical aficionados of English

drawing room comedy and older followers

of old movies where pukka chaps had stiff

upper lips and stiff moustaches, the whole

upper class apparatus from top hats

to gardenias in the buttonhole, will remember

his father, the actor and playwright

Hugh Williams, whom he writes about so affectingly.

The actor first flared in Hollywood in the Thirties,

disappeared into the Army for the duration

of the war, then re-emerged suave and grey

as actor-author, presiding over the drinks tray

in a series of debonair light comedies,

which allowed him to play himself

in the world he knew best – a forgotten world,

re-created here by his son.

Ransacking old letters, he has raided the past

to imagine himself into his father’s life

and personality. As the lives of father and son

loom clear, perception of the past is altered.

Reflections shimmer back and forth

as we watch Hugo Williams strolling through

the long twilight of upper middle class

light comedy, arm in arm with his son.

Brow

The brow of the hill rose steeply

ahead of me, a patch of light

like a window in its polished surface.

I would set my foot on that slick

of black ice, its luminous white line

would lead me before long

over the horizon of my father’s head.

The Mouthful

Flights of steel-tipped arrows

pass across my father’s face

as he looks around the table.

His widow’s peak is pulled down

like a Norman helmet.

His eyes are shrapnel.

His irises are wearing

little white spectacles of bacon fat

to examine my plate.

He tells me it’s rude

to push my food around,

making dams out of mashed potato

when other people are eating.

He has loaded his fork

with a top-heavy parcel

of peas and underdone lamb,

added mint sauce and redcurrant jelly

and hoisted it to his lips.

He tips his head to one side,

as if he is listening,

shuts his eyes for a moment

and lets his jaw go slack.

It quivers slightly, opening wider

to allow the mouthful to go in.

I clench my fists under the table

and draw strength from a fly

that is sitting feeding in his parting.

Fur

I traced the makers

of his musquash-lined evening coat

from a label in the pocket

to a basement in Cork Street

and discussed repairing it with a man

who didn’t remember my father

or the white waistcoats

they used to make for him before the war,

but smiled and shook his head

and suggested pulling out the fur

to sell separately

and offered me ten quid.

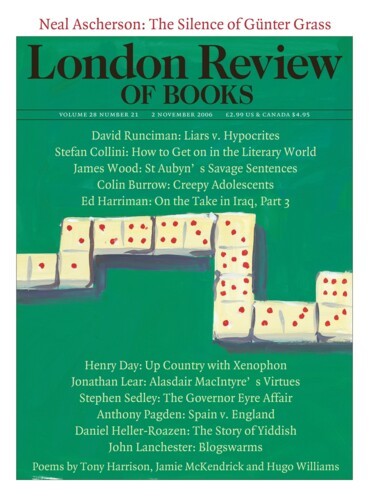

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.