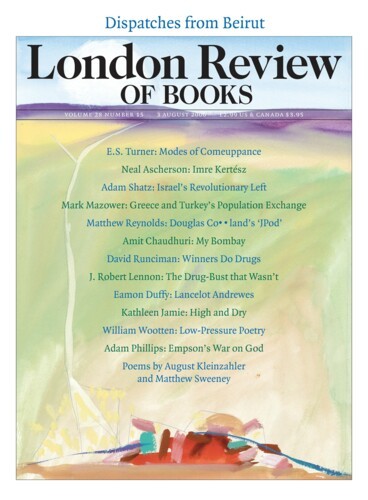

Douglas Coupland’s new book is both more than a novel and less. There is a JPod website where you can see the six main characters represented as Lego figurines, hear some of their favourite songs, and join in ‘pod pastimes’ – not much at present beyond selling yourself on eBay, but more is said to be ‘coming soon’. A ‘special edition’ of the novel includes a freebie Lego figurine: why not collect the whole set? Yet while the book-as-commodity expands into new media and merchandising, the book-as-fiction shrinks. Within its covers there are pages of pseudo-factual material cut and pasted from the textual world outside: labels for noodle soup and Doritos, advertising copy for the Subway sandwich franchise, and spam emails offering penis enlargements and fat sums of money from Nigeria.

This no man’s land of media culture is Coupland’s home ground. The astonishingly full and varied body of work that began with Generation X in 1991 is populated by alienated characters: a beauty queen, a medium, people caught up in human-interest news stories (high school shooting, disabled astronaut, woman in coma gives birth). For his non-celebrities, too, the world has come ready-formatted: by 1980s TV or Disney or ads for grooming products or mass evangelism. The books revel in all this. They are packed with tabloid-style plot entanglements – mother gets HIV when husband shoots bullet into her through son’s infected body – and carefully observed trashy language: ‘I see a fleet of Jeeps, pick-ups, and 4WDs bearing major Halogen light-show action, plus Skye’s Wagoonmobile (her mother’s rusted AMC Matador sloppily painted with daisies, peace signs, and pine trees and the license plate LIVED B4) and Harmony’s Celica PRV, beating us here from the gym (the Princess Rescuing Vehicle, licence plate: YE GEEKE).’ Like all good satirists, Coupland loves his targets. This passage may be a critique of the interdependence between personal style and corporate branding, but its cacophony of signs also says: enjoy!

Yet always, until now, Coupland has held onto a distinction between his own writing and the texts consumed and produced by his characters. For all their media literacy, his people are never great readers of novels: by putting them in a novel he sees them differently from the way they see themselves, even when the narration is in the first person. Coupland looks through the darkened glass of satire, but he has a visionary lens, too, through which he imagines his characters’ redemption.

This messianic ambition is signalled in images which take the emblems of a packaged world and connect them to something beyond: ‘the pacific sunset, utterly unused and orange and clean, like shrink-wrapped exotic vegetables’; ‘his eyes were the pale blue colour of sun-bleached parking tickets.’ These comparisons have a double impact. They nail the characters who see things that way; and they flag the inventiveness of the writer who does the nailing. His imagination is sharp enough to grasp the flatness of theirs, and generous enough to make beauty from it.

According to the usual trajectory, Coupland’s characters are released from their commodified perceptions into feelings that count as ‘real’: love and/or untrammelled awareness of the natural world. The sun emerges from its shrink wrapper, and the novel (Miss Wyoming, 2000) that began by slapping parking tickets on people’s irises ends up rescinding them: ‘Susan’s eyes were as wide and open as the cobalt sky above.’ The revelations are wordless, like the total immersion in a stream that concludes the story ‘1000 Years (Life After God)’, or millenarian, like the vision of global catastrophe that is granted to a bunch of teens in Girlfriend in a Coma (1998), or surreal: in Shampoo Planet (1993) a ceiling collapses under the weight of an indoor carp-pond, sending the menagerie flopping down into the apartment below. ‘“Wake up,” I say. “Wake up – the world is alive.”’

These moments are clearly meant to matter, but the switch from satire to bearing witness has always felt uneasy. The explicitness of the rhetoric and the obvious rose tinting (what became of the carp?) pull the revelations back towards the confected world they were intended to break through. You might dismiss them as a hippyish injunction to ‘wonder’, aimed at the popular audience Coupland has always nurtured. Yet their reverent tone and persistent Christian echoes – baptism, the Last Day, the Garden of Eden – make a deeper claim. Coupland seems to be serious about his mysticism, in a shy sort of way. He shares the old worry at having to use words to assert the value of wordlessness, at the deadening effect of banging on about the need to be ‘alive’.

His last two books, Hey Nostradamus! (2003) and Eleanor Rigby (2004), stand out from the rest because they recognise this difficulty and imagine ways through it. Their redemptions are harder won, and the movement towards them is worked into the text from the start. Eleanor Rigby’s life story, for instance, is extraordinary and sounds like a vehicle for schmaltz: her son, given up for adoption when she was a teenager – she had been so drunk she didn’t even know she had had sex – returns to her as an adult, only to die of MS; and then she discovers that she loves his father, an Austrian she was never aware of having met. The Christian template is evident: sort-of virgin birth followed by sort-of resurrection followed by just-about-sort-of assumption into heaven. But the complex characterisation, the lack of knee-jerk satire and the tentativeness of the narrative keep it the right side of miraculous.

JPod replays many of Coupland’s signature themes, but lacks any spiritual modulation. The book it most revisits is the one with the most thinly imagined happy ending: in Microserfs (1995) a bunch of overworked geeks leave Microsoft, go to California and set up their own software company, writing Oop!, a game of virtual Lego. It is nice down there – ‘so alive!’ – and their personalities in various ways flower. All this is narrated in a laptop diary by one of their number, Dan. There is much sharp, sweet observation of techie oddities and group dynamics, and much fun with formatting: at one point Dan splits his words across two pages, consonants to the left and vowels to the right. When Dan’s mother has a stroke we are asked to feel that it is not too much of a downer, since she can communicate via a keyboard in a vowel-depleted shorthand. ‘All of my messing around with words last year and now, well … it’s real life,’ Dan says – the idea apparently being that language can connect to ‘life’ so long as it stays electronic. In the general atmosphere of redemption via word-processor Dan somehow comes to feel that his long-dead brother has been returned to him too.

In JPod no one would think of writing a computer game as a way of being born again. Now, big business messes around with words. The novel takes its title from the characters’ workgroup, which has been created by an arbitrary alphabetic tyranny: employees whose surnames start with ‘J’ are sent there. This time round, the bunch of geeks, labourers for a big software company in Vancouver, are already at work on a game: even fun is corporate now. The game starts off ‘generic’ but the new marketing man, Steve, wants to make it distinctive by inserting ‘a charismatic cuddly turtle character’. But this ‘charisma’ is generic too: the character is modelled on the cheesy presenter of Survivor, Jeff Probst, and is derivative of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise. So the program is made over into a fantasy adventure called ‘SpriteQuest’, itself indebted (though no one admits this) to a real game called ‘Elfquest’ – not to mention the fizzy drink. Disgusted, the geeks try to subvert the new version by inserting a sociopathic Ronald McDonald character; but this attempt at sabotage is happily absorbed and marketed by the corporation.

The usual Coupland escape route into Nature is now closed. Roads are ‘treeless’; a rainforest has been ‘bulldozed to make way for jumbo houses’. In Eleanor Rigby and Shampoo Planet, foreign travel was transformative, but here a trip to China yields only grey: ‘All you’d need to portray the place is an HB pencil, and then dip your brush in a spittoon,’ the narrator, Ethan, says. His love interest, Kaitlin, is rebelliously perceptive, just like Karla, the narrator’s love interest in Microserfs (across Coupland’s work there is a KPod of sparky young women). She tells her co-workers that they have no ‘character’, that they are nothing but depressing assemblages of ‘pop culture influences and cancelled emotions, driven by the sputtering engine of only the most banal form of capitalism’. In Microserfs this sort of protest led to lifestyle revolution. Second time around it is only a passing strop, something to be absorbed into the routine of the working day:

We heard a cat yowl from behind our cubicle wall: Kaitlin. ‘You people are driving me absolutely fucking crazy. All you ever talk about is junk.’

I looked over at her – brown hairs Van de Graaffing from her forehead; a pimple she’d been hoping nobody would notice caked in skin product; small, perfect teeth. I was wondering what her kiss would taste like, when she picked up a Clive Cussler novel that everyone in the pod had read, and hucked it at the wall by the air intake.

Bree encouraged her. ‘You throw that book, Kaitlin! Get it all out!’

She gave another snared-in-the-leg-hold cry, then hurled an N64 development folder from 1998, followed by a hardcover copy of If They Only Knew, the 1999 autobiography of World Wrestling Federation sensation Chyna.

After this, she seemed as spent as Mr Burns handing a shovel to Smithers after throwing a handful of dirt onto a grave, and she spoke in the one word sentences used by exhausted slaves: ‘All. I. Want. To. Do. Tonight. Is. Design. A. Realistic. Looking. Waterfall. Ripple. Texture. Is. That. Too. Fucking. Much. To. Ask?’

‘I think we should all get back to work,’ I said.

So many stifling elements so expertly blocked in: the crap books good only for throwing at the wall; The Simpsons and the movies as the points of comparison (where has Ethan encountered exhausted slaves?); the return to work as the only way forward. It’s a very cold sort of comedy.

Generation X celebrated narrative as a means of support: ‘Either our lives become stories, or there’s just no way to get through them.’ In JPod the characters are kept going by routine. Routines can be tuneful: unsurprisingly, in a book whose title echoes the iPod, JPod boasts karaoke, ballroom dancing – and choruses like this one, prompted by someone’s bringing a McDonalds into the office: ‘Heads and bodies appeared as if on cue in a Broadway musical: The Taint? The Taint!’ Or they can be numerical, like the routines computers go through: the JPod geeks love trying to spot one wrong digit inserted into the first 100,000 places of pi (all printed out so we can join in), or a letter O instead of a zero in a list of 58,894 random numbers. Narratives tend to individuate, routines tend to generalise: they ask to be repeated and are easily done in groups.

In interviews, Coupland describes himself not as a novelist but as an artist who writes. JPod’s way with text – including its pages of numbers – owes much to contemporary visual art and has little in common with other novels, even those that are called experimental. Usually in such books – in B.S. Johnson, say, or Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2005) – the messing around with words is designed to be expressive: this page is split in half because the character is in two minds; this page is fragmented because the character cannot hear. The typographical oddities aim to make the text mean more.

But Coupland evacuates meaning by extracting words from their contexts. Take the following, one of several found texts printed in large type:

Increasing

Effectiveness

through

Situational

Leadership®

This works like Jenny Holzer’s ‘truisms’ projected onto buildings or printed on T-shirts. There it is: what do you make of it? How does it connect? In Microserfs, such snippets were firmly placed in Dan’s ‘subconscious files’; in JPod they float bafflingly free. We can guess that this slogan has to do with Ethan’s desire to rise to the rank of production assistant, but whether as cause or as consequence we cannot say.

Other inserts are transcribed food labels. Like the labels created by Damien Hirst in The Last Supper, they emphasise food’s constructedness and connect reading to the routine of eating. A series of alphabetical lists – of acronyms, of three-letter scrabble words – set up yet another routine, one which exerts an eerie power when a challenging, impersonal voice – apparently the voice of ‘our culture’ – gets infected by alphabetical order. Language circulates through the book in ways that are semi-ordered, designedly inauthentic and largely disconnected from people.

Events unfold not so much in a plot as in a series of loosely connected conceptual art installations. Ethan’s mum electrocutes a threatening biker in the basement marijuana grow-op of her suburban home. Ethan finds that his apartment is full of Chinese immigrants who have been dumped there by Kam Fong, a people-and-drug-smuggling associate of his brother’s. Kam Fong goes ballroom dancing with Ethan’s dad. Steve, the marketing man, who has been hassling Ethan’s mum, is abducted by Kam Fong and then found by Ethan working on a production line in China, addicted to heroin. There is an outbreak of ‘Cat-Related SARS’ in the factory but Ethan and Steve are rescued by someone called Douglas Coupland, who extorts Ethan’s laptop as payment. Steve’s mum has a bit of a thing with freedom (lower-case ‘f’), the lesbian mother of one of Ethan’s co-workers who has changed his name to John Doe and strives ‘to be statistically normal to counteract his wacko upbringing’. Ethan’s dad keeps failing to get a speaking part in a movie but his moment comes as the voice of the computerised Ronald McDonald: ‘I shall pierce your being with shakes made of ground bones, nay, chalk.’

Meanwhile, the pod’s routines have continued and Ethan and Kaitlin have rather cursorily got it together. Then everyone goes to work for Coupland and Kam Fong on a great business idea, Dglobe. This is a beach-ball sized globe on which you can watch the history and future of continental drift, or of the world’s weather, or ‘a colour-coded slow-speed mapping of human populations on the planet since 5000 BC’: ‘Everyone in the world is going to want one.’ Ethan thinks of this as a happy ending, but his shiny protestations – ‘Yesirree, life sure is good’ – seem as shallow as a painting by Gary Hume.

Coupland is often called a zeitgeist author but here – and I think always – he is no less interested in the spirit of place. His two Souvenir of Canada volumes give many reasons for thinking of JPod as a book about Vancouver (‘indoor grow-ops are an entrenched way of cash-crop farming in Vancouver … they surround my parents’ house’). But these days, with cheap flights, the global market and Google, places aren’t as particular as they used to be: the roll-out vision for Dglobe – a world in every sitting-room – is not so different from Google Earth. With its internationally owned property, and its international trade in software, drugs and people, JPod’s Vancouver is, in part, an anywhere. And Coupland, an internationally marketed novelist, contributes to this expansion, which is also a loss. That is why ‘Douglas Coupland’ is so much shiftier than his nearest relative, the ‘Paul Auster’ of City of Glass, and why he is in partnership with Kam Fong, the smuggler of drugs and people.

JPod offers itself not – like Coupland’s other novels – as something different, warm-hearted and transformative and true, but as one more product in the global circulation of text. Hence the website tie-in and the Lego merchandise. The running analogy between the book and a computer game reinforces this point (the last words are ‘Play again? Y/N’), as does the flattened style and the way all the characters – even Kam Fong – sound the same. It is an extraordinary book, wide-ranging and wildly inventive yet also overwhelmingly drab. In a mini-essay on her life for a course she is taking at the Kwantlen College Learning Annex, Kaitlin remarks that ‘the air smells like five hundred sheets of paper’. JPod occupies 449 pages and doesn’t leave you much room to breathe.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.