It has become the odour of the age, flowers rotting in their cellophane wrappers. People began laying them on the steps of St Pancras Church the morning after the 7 July bombings, and within a day or two the steps had been transformed into a slope of glinting paper, the flowers strangely urban behind the police cordon. It was also a slope of words: handwritten messages, emails, shop-bought cards and pavement script. The church’s columns were chalked with words too, and the Word of God – a King James Bible, ‘User’s Guide on Back’ – appeared to float unabashed on a sea of London scrawls.

For a few days after the explosions, the atmosphere was bad on the buses. Passengers were looking into every face as they sat on a Number 30 from King’s Cross, and if the face happened to be brown, they looked to their bag or backpack. That is how fear and paranoia work: they create turbulence in your everyday passivity, and everyone was affected after the attempted bombings on 22 July in ways that won’t quickly go away. In the realm of paranoia, the second bombings were more powerful than the first, for they made it clear how very gettable we are, even in a culture of high alert. To anyone with imagination (or who knows anyone who’s ever had a second stroke) the most recent attack brings a dimension of constant threat. No one needed to die for this to take effect: 7 July showed us what death on the bus or the Tube looks like; the second attack showed that these images wouldn’t be allowed to remain just a bad memory. Sitting upstairs on the Number 30 a few days after 7 July, I found myself thinking: in this seat, would it be a leg I’d lose, or an arm? Would I die instantly? Or would I be one of those walking around afterwards in a daze? The London bombings are an ontological disaster for anyone who commutes in a big city: the blasts have taken the steadiness out of people’s expectations and replaced it with a more or less hysterical dependence on the size of their luck. That sort of thing is okay from a distance, but it can punish your spirit on the down escalator at nine o’clock in the morning.

When the Number 30 passed a statue of John F. Kennedy in Marylebone Road, a teenager looked up at his mother. ‘It all started with him,’ he said.

‘I know what you mean,’ his mother said. ‘He was the first to get this amount of coverage.’

In Regent’s Park rows of old ladies were sitting in the rose garden. In their white skirts and sandals, they had an air of seen-it-all about them, pointing to beds of flowers and thinking nothing of cellophane. And maybe they had seen it all: by the boating pond, fixed to the bandstand, was a plaque engraved with yet more London words. ‘To the memory of those bandsmen of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Green Jackets who died as a result of the terrorist attack here on 20 July 1982.’

The remains of the Number 30 bus were covered in blue tarpaulin and removed from Tavistock Square a week later. In the days when the street was blocked off, when Upper Woburn Place became a forensic scene and a no-man’s-land, I found myself quietly hankering after the openness of Tavistock Square, and several times that week I came down to look at the barricade and puzzle over the idea that the square had gone. I wondered if the street had not lost its life too, as often happened in the Second World War, when people would arrive to mourn both the dead and the place where they used to go. Among many things, the bombings gave those of us who are attached to the city a sense of what it might be like to be very old, to see a graveyard at the corner of every street, a bar where some dead friend used to drink, a bench where you once got a kiss.

There’s an essay by Cyril Connolly, ‘One of My Londons’, in which he writes of London as a city of prose. At the point of writing the essay, Connolly found it hard to be in London for more than a few days at a time, so freighted with former lives were the streets around Fitzrovia, so haunted by memory and well-honed sentences. The square that is formed by King’s Cross, Lamb’s Conduit Street, Tottenham Court Road and Warren Street is one of my Londons, and the very centre of that London is Tavistock Square. If London is a city of prose, then this is the capital’s capital, a square of reason and memory and imagination. My home’s home.

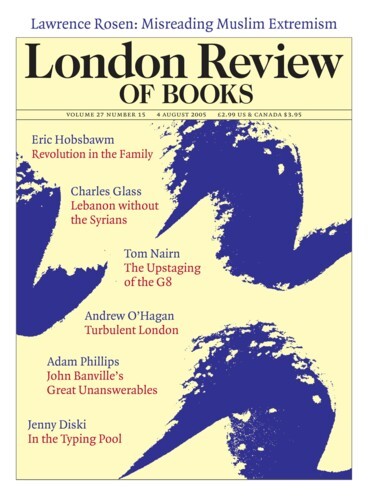

The London Review of Books had its offices in Tavistock Square for almost ten years. We were housed in a couple of rooms on the third floor of the BMA building, Entrance C, where the great blue door is now shattered and the windows pierced. The paper bears no deeper connection than that to this terrible event, and the pictures of Entrance C spattered with gore will alter every Londoner’s sense of London, not just those who knew the doors and the square they open onto. Yet proximity is the currency in a culture of bomb-fear: those of us who used to come to that place every morning might be allowed to pause for a second in our own way. The London Review sent out prose, and poems, from that building every fortnight, and one day a young man came to the door with a bomb strapped to his back.

Standing in the square the other day, trying to ignore the statue of Mahatma Gandhi – it’s not hard to ignore, both because of its ugliness and the minatory nature of his peaceableness – I reached for the answer. But the answer, of course, was there all along: more thought. More argument. For Blair to deny that the invasion of Iraq influenced the bombers is an insult to both language and morality. For Islamic extremists to pretend that their cause will not be set back in Britain by targeting buses and tubes is a murderous delusion. Blair’s war has been a drafting exercise for young jihadis, and the efforts of the young jihadis will be a drafting exercise for the British National Party. Welcome to Endgame England.

Several of the victims of the bus bombs were taken into the forecourt of the British Medical Association, where they were attended to by as many doctors, and where two passengers died. I was always amazed by the length and circuitousness of the corridors in the BMA building, which made one feel like a lost blood cell travelling through the arteries of some giant corporate body. Our office seemed so small and tight compared to all that expanse, but it was to those rooms, with their windows looking down on Tavistock Square, that Salman Rushdie once delivered his review of Calvino’s Invisible Cities, and where it was edited, cared for, ‘washed and ironed’, as the editors would say. ‘Why,’ he wrote, ‘should we bother with Calvino, a word-juggler, a fantasist, in an age in which our cities burn and our leaders blame our parents? What does it mean to write about non-existent knights, or the formation of the Moon, or how a reader reads, while the neutron bomb gets the go-ahead in Washington, and plans are made to station germ-warfare weaponry in Europe?’ He went on: ‘The reason Calvino is such an indispensable writer is precisely that he tells us, joyfully, wickedly, that there are things in the world worth loving as well as hating; and that such things exist in people, too.’

Those were the same rooms where Tony Blair arrived breathlessly one day before catching the train at Euston. The piece he delivered may have required more ironing than Rushdie’s, but it too, in October 1987, found its place in the paper’s pages. He wrote that Mrs Thatcher ‘will wield her power over the next few years dictatorially and without compunction’ and further predicted that ‘the 1990s will not see the continuing triumph of the market, but its failure.’ And it was into those same rooms that Ronan Bennett came with one of the longest pieces ever published in a single issue of this paper, a report on the civil and legal injustices perpetrated by the state in its desperate pursuit of those guilty of the Guildford bombings. Argument in the long run is louder than bombs, even if, as often happened in my day at the London Review, people would ring up to cancel their subscriptions when they violently disagreed. It was mostly after we’d run a piece by Edward Said. ‘I refuse to read pieces written by murderers,’ one of them said.

‘And we’re happy not to publish them,’ I said.

‘Said is happy to see Israelis bombed,’ she said.

‘No,’ I said. ‘Professor Said is happy to make arguments, and we are happy to publish them.’

But it was Tavistock Square itself that was on my mind. It is understandable that condemnation, in such a case as this, will precede contemplation, but perhaps less bearable that we live at a time when it will overthrow honest thinking altogether. The square is a living testament to the opposite view. More than a hundred years before people were phoning to complain about Edward Said’s right to write, Charles Dickens was furnishing his new house on the same site, and furnishing his new novel, Bleak House, with characters who struggled to agree about how to live in the world and what to believe. Peter Ackroyd provides a nice picture of the novelist in the agonies of trying to complete his new house, sitting disconsolately on a stepladder while ‘Irish labourers stare in through the very slates.’ A later visitor, Hans Christian Andersen, saw a magnificent 18-room house, filled with pictures and engravings. But nothing is simply one thing, not even the reputation of a great house, and Dickens’s pile on Tavistock Square drew ire from George Eliot. ‘Splendid library, of course,’ she wrote, ‘with soft carpet, couches etc, such as become a sympathiser with the suffering classes. How can we sufficiently pity the needy unless we know fully the blessings of plenty?’

The commentators spoke almost by rote about how the bus explosion on Tavistock Square was ‘unimaginable’, and it was pretty unimaginable, all the more so in a place where so much had been imagined and where people had lived, indeed, fully in accordance with their empathetic capacities. We used sometimes to have a drink after work at the County Hotel, which looks out to Upper Woburn Place with a rather doleful quiver about its nicotine-stained jowls. Everybody who came into that bar – railwaymen from Euston, dancers from the London School of Contemporary Dance – carried a very large sense of particularity about them. Maybe it was the lighting. In among the half-pints of bitter and the curly sandwiches, something in the atmosphere of that bar, with its giant 1940s radio, made everyone seem discrete and minutely alive, not like the hordes of Southampton Row. Everybody smoked cigarettes in those days. There was no television and nobody had a mobile phone. They served lemonade out of bottles. It was heaven to me.

Dorothy Richardson lived at 2 Woburn Walk, the narrow passage next to the County Hotel. It was a ‘flagged alley’ in 1905, a ‘terrible place to live’, she wrote. Nearly under the shadow of St Pancras Church, Richardson’s flat stood above a row of shops (as it still does), a stonemason’s, in her case, while across the alley, at Number 18, W.B. Yeats had one of his London addresses. Richardson recalled seeing him standing at the window on hot summer evenings, breathing the ‘parched air’, as she called it. In his biography of the poet, Roy Foster reports that ‘the flat at Woburn Buildings was scraped and repapered in an effort to remove insect life, though WBY still returned there for his Monday evening entertainments.’ It appears that Dorothy Richardson was never invited; she and Yeats never actually spoke, though years later she remembered them almost bumping into each other in Tavistock Square. ‘For memory,’ she wrote, ‘we stand permanently confronted either side of that lake of moonlight in the square.’

Like Hasib Hussain, the Number 30 bus was a stranger to Tavistock Square. But the 18-year-old who wasted his own life and 12 other people’s on that bus knew something about the poetry of Yeats. The bomber had seven GCSEs, including one in English, and Yeats was one of his topics. Heaven knows what was on his mind when he set off his terrible backpack that morning, and one can only be sad that it wasn’t Yeats, a one-time neighbour to his terrible, beautyless act, or his poem ‘Easter 1916’, a distillation for me of the saving power of two-mindedness, the great theme of old Bloomsbury.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.