In 1945, Somerset Maugham contributed a list to Redbook magazine of what were, in his opinion, ‘the ten best novels in the world’. Maugham’s choices were neither surprising nor controversial (War and Peace, Madame Bovary, Moby-Dick) but in a note that accompanied his list, he suggested that ‘the wise reader’ will ‘get the greatest enjoyment out of reading them if he learns the useful art of skipping’. Skip, then, to the moment when the American publishing house John C. Winston Company, taking Maugham at his word, hired him to demonstrate this art. Under the series title ‘Great Novelists and Their Novels’, the books Maugham had chosen were issued in new editions ‘edited by W. Somerset Maugham’ in 1948. In an essay inaugurating the series, Maugham explained that ‘the novel is essentially an imperfect form . . . to be read with enjoyment. If it does not give that it is worthless.’ Noting that ‘readers in the past seem to have been more patient than the readers of today,’ that ‘they had more time to read novels of a length that seems to us now inordinate,’ Maugham explained that ‘it is to induce readers to read them that this series has been designed’:

The attempt has been made to omit from these ten novels everything but what tells the story the author has to tell, exposes his relevant ideas and displays with adequacy the characters he has created. Some students of literature, some professors and critics, will exclaim that it is a shocking thing to mutilate a masterpiece, and that it should be read as the author wrote it. But do they actually do this? I suggest that they skip what is not worth reading, and it may be that they have cultivated the art of skipping to their profit; but most people haven’t: it is surely better that they should have their skipping done for them by someone of taste and discrimination.

Here’s a paragraph Maugham struck from the first chapter of Madame Bovary:

It would be impossible now for any of us to remember anything about him. He was a levelheaded boy who played during playtime, was diligent in his studies, attentive in class, slept well in the dormitory, ate well in the refectory. His local guardian wholesaled hardware on rue Ganterie, taking him out once a month, on Sundays after he closed up shop, sending him to walk around the port to look at the boats, then bringing him back to school by seven, for dinner. Every Thursday evening, he wrote a long letter to his mother in red ink, using three sealing waxes; then he went over his history notebooks, or read from an old volume of Anacharsis that was always lying around. When he went for walks, he chatted with the maid who, like himself, was from the country.

Maugham has skipped Charles’s undistinguished boyhood at boarding school; his dutiful epistolary regime; his rapport with the maid (the only woman that a boy who missed his mother got to be near). He systematically blurs our view of Charles, removing the images that might linger in a reader’s mind (the red ink, the sedulously applied sealing wax), and trims away anything that doesn’t directly and explicitly advance the plot. The ‘relevant ideas’ that underlie this paragraph are, for Maugham, already displayed ‘with adequacy’ elsewhere. The seeds of the blundering doctor into which the very average Charles will sprout, the roots of the loneliness that will make him susceptible to the charms of any woman no matter her nature: both pervade the chapter’s soil. And yet Maugham’s versions – however discriminating and logically justifiable his exclusions – didn’t attract readers: his svelte hit parade (‘uniform in size and design’) never caught on, and soon went out of print. The reason was clear. Maugham had left us the stories of these novels but had robbed us of one of the chief pleasures that fiction provides: access to the unreasonable excess produced by another mind.

There is little that is excessive and much that is reasonable in the early novels of the young American writer J. Robert Lennon. At 34, Lennon, already the author of four novels, plots his books with a rigour and restraint uncharacteristic of writers of his generation. Whereas his immediate contemporaries Dave Eggers, Colson Whitehead and Mark Danielewski all thrive on – and have in part made themselves known for – work that brims with clever digression, Lennon includes only what advances his plots and broadens our sense of his characters. In an era where a species of self-congratulatory prose is often mistaken for writerly talent, Lennon’s unselfconscious style does not assault the reader with reminders of its hipness. It is perhaps for these reasons that Lennon is relatively unheard of in America, despite having written books more satisfying and moving than those by his better-known peers.

Each of Lennon’s first three novels begins with a destabilising event the tremors of which reverberate through the narrative until order is, at last, firmly restored. In The Light of Falling Stars (1997), a plane crashes behind a couple’s home in rural Montana, initiating a search for survivors (the book ends when the fate of those on board is at last made clear); in The Funnies (1999), the famous cartoonist father of a large, unhappy family he has memorialised in a newspaper strip dies (the book ends when the baroque provisions of his will are fully enacted and family conflicts are finally resolved); in On the Night Plain (2001), the son of a sheep rancher leaves his family in Montana to make his way in the world (the book ends after the son returns and comes, with time, to accept his birthright). But although he sets these books in motion with big events, it is in his handling of small moments that Lennon has distinguished himself. In The Light of Falling Stars, the couple who saw the plane crash and who are on the brink of separation, take a bath together that provides a valedictory intimacy:

She climbed back into the water, her breasts long and slender from the pull of gravity as she stood above him . . . [He] understood that this was what he was in danger of losing – this privilege of seeing her body at its most raw and practical. The muscles in her thighs went taut as she sat, her shoulders bowed; this was unsexual and beautiful to him, and the loss was a great, awful vacuum in his chest, pulling at anything he seemed to have left inside him.

In The Funnies, the dead cartoonist’s son, who has been left his father’s cartoon strip, must learn to draw the members of a family he neither understands nor particularly likes, parsing the pen and ink physiognomies that reveal character, in particular that of his dead father: ‘That slouch he gave himself, I think, expressed backhandedly a despair he was loath to express explicitly. It was a great and subtle slouch, just the faintest forward collapse of the shoulders, the merest fold of gut jutting out over his belt. He looked like he was in constant danger of toppling over, onto his face.’ In On the Night Plain, the rancher’s son’s thoughts about sheep betray his growing appreciation of the integrity of the life he had abandoned:

Once he’s seen a flock move across a hillside and mistook it for the shadow of a cloud. He had watched sheep gather where they once found a salt lick years before, even the lambs, who hadn’t been alive to see it. A sheepflock seemed to pulse with purpose almost as if it was one creature, a vast and simple mind that understood its relationship to the land and to man, while a herd of cattle was nothing more than a vegetable garden with hooves, a lowing orchard, inefficient and dumb.

Lennon’s writing is always intelligent, occasionally exceptional; characters, always artfully sketched, sometimes take on a human heft; late moments in the books consistently yield emotional dividends: these novels work, but they work familiarly, providing comforting resolutions rather than complicated revelations. Despite its glaring shortcomings, John Henry Days, Colson Whitehead’s uneven book, nonetheless contains – thanks to its daring and ambition, its willingness to take risks that sometimes don’t come off – stretches of writing (the chaos of Altamont, the myth of John Henry’s last days) far more memorable than anything in Lennon’s more consistently achieved productions. Lennon’s first books are less necessary works for readers than they were necessary books for their writer.

Lennon’s fourth novel, Mailman (2003), showed him staking a claim to terrain all his own. He shed the narrative strategy that had served him in his first three books. Rather than an immediate, destabilising event at the outset, Lennon establishes an unstable central character slowly and deliberately. A long first chapter takes us literally step by step through a day in the life of Albert Lippincott, a postman in a small upstate New York college town. In the place of a conventionally unfolding plot, Lennon gives us access to Lippincott’s unconventional thoughts as he follows his delivery route, allowing us to assemble, through these apparently offhand musings, an evolving sense of his character. The third-person prose reflects Lippincott’s amusing but unamused sense of the world around him on a day when his town is holding its annual fair, a ‘citywide jerkoff . . . full of longhairs hawking their cheesy doodads out of plywood booths, restaurateurs setting up greasepits on the sidewalk, experimental theatre groups emoting in intersections . . . and everywhere a plague of little kids.’ With each stop Lippincott makes, he deposits mail for his customers while Lennon leaves clues for his readers. We might wonder, say, why Lippincott’s car contains a conspicuous quantity of ‘broken office supplies’, but slowly we learn that Lippincott ‘borrowed’ mail from his customers, mail which he would open, read, photocopy and reseal with the office supplies before at last delivering it. We come to understand that, for all the vibrancy of his thoughts, Lippincott leads a deadeningly lonely existence, his chief connection to the world his contact with the lives of the people whose intimacies he steals. And only at the end of the chapter – 65 pages into the novel – does the reader learn that one of Lippincott’s customers suspects he is up to no good. Whereupon the motor of the plot finally turns over.

The possibility of discovery threatens Lippincott’s every forward step. And yet, most of the steps the novel takes are backwards. For five hundred daring pages, Lennon gradually unclenches his grip on Lippincott’s past, allowing his meandering thoughts to fill in the gaps in our understanding of a man’s 57 mostly wasted years. Lennon explores character and consciousness at a greater depth than the shapely narrative bustle of his earlier books allowed. Here, Lippincott recalls a plane trip during which the young woman sitting next to him fell asleep on his shoulder:

He himself ought to have slept . . . but his thoughts had changed gears, each unscrolling itself discretely . . . He saw the thoughts arrayed on a gleaming wood floor . . . like rugs . . . unreflective patches on the bright boards clear and colourful, drinking up the light; in the corner he could see his unthought thoughts rolled and fastened with twine and tagged, and on the tags were written the contents of the thoughts – food, sex, cats, mail – that were not on his mind just now but ought to be close at hand. And of course by now he really was asleep, he felt [the woman’s] small round hair-cushioned skull under his left ear and imagined that he could hear her thoughts unscrolling, could hear the rug merchant of her mind bartering, displaying one thought, putting another away, concealing the very finest and most secret beneath his table for some select customer, some ideal buyer who had not yet approached him but would, most certainly, someday.

Mailman marked a leap forward for Lennon. Whatever its excesses – a wilfully attenuated beginning, an excessively neat ending – Lennon revealed, believably, the teeming emptiness within one insignificant man. This marked change of method was noted during the book’s reception, which was both more abundant and more abundantly mixed than that of earlier outings. Although some called Mailman the masterpiece it is not, a consistent criticism was also levelled. Writing for this paper, Theo Tait, in a largely favourable review, said that Lennon’s novel ‘could easily be a hundred pages shorter than it is’; in the US, Publisher’s Weekly said that it was an ‘intermittently brilliant text – with long, maddeningly tedious patches’. These criticisms seem to have stuck. On his website, below the Publisher’s Weekly review, Lennon added, good-naturedly (in the only reply to the reviews that appear on his site): ‘With Hans-Blix-like determination, we are still searching for the maddeningly tedious patches and will report to you, the readers, when we find them.’

Now that report seems to have arrived, but under a very different cover. Pieces for the Left Hand consists of 100 very short stories, all of them about a page long, in which not a word is wasted, and not one of which could be cut. Despite its self-deprecating title, the collection is anything but offhand: it is a rigorous display of storytelling verve, quantity and control. For Lennon the novelist, the book represents a sidestep, but a very profitable one: it is his most perfect work so far, achieving the originality that escaped him in his first three novels and the consistency that eluded him in his last.

These ‘pieces’ compress the longueurs of O. Henry’s brand of irony into fable: they are bedtime stories for adults. All unfold in a small town in New York state. An introduction suggests that they are the product of a local, the unemployed house-husband to an academic wife. He is said to take long walks; his stories – some invented, some recalled – come to him while he travels ‘through fields and forests, hiking along the shoulders of roads’. Each brief narrative excursion dramatises some kind of misreading of the world. Each features a surprising transformation, a reversal of expectation: the name of a town’s main street is changed, the change produces protests, protests undo the change, the undoing leaves the street nameless; a girl caught painting ‘trust jesus’ on a bridge is forced to whitewash it as punishment, and its surface soon becoming a target for teenagers who fill it with obscenities. These brief pieces share a melancholy rhythm. In form, all resemble one another like members of a family, but they are all distinct. It eventually becomes clear that the town in which the stories are set is the town that hosted Lennon’s last protagonist; both have a conspicuous feature: ‘a set of sculptures, models of the planets rendered in stainless steel and balanced on four-foot pyramidal spires’. The larger parallel this suggests is that these two books provide alternative but comparable models for describing a world. While Maugham would certainly have preferred Lennon’s latest series of descriptions, with their elimination of ‘tedious patches’ and ‘cumbersome dissertations’, Lennon understands that different forms bring different benefits, the empathy accessible through the abundance of the novel, and the wonder achievable through brevity:

A local novelist spent ten years writing a book about our region and its inhabitants, which, when completed, added up to more than a thousand pages. Exhausted by her effort, she at last sent it off to a publisher, only to be told that it would have to be cut by nearly half. Though daunted by the work ahead of her, the novelist was encouraged by the publisher’s interest, and spent more than a year excising material.

But by the time she reached the requested length, the novelist found it difficult to stop. In the early days of her editing, she would struggle for hours to remove words from a sentence, only to discover that its paragraph was better off without it. Soon she discovered that removing sentences from a paragraph was rarely as effective as cutting entire paragraphs, nor was selectively erasing paragraphs from a chapter as satisfying as eliminating chapters entirely. After another year, she had whittled the book down into a short story, which she sent to magazines.

Multiple rejections, however, drove her back to the chopping block, where she reduced her story to a vignette, the vignette to an anecdote, the anecdote to an aphorism, and the aphorism to this haiku:

Tiny Upstate town

Undergoes many changes

Nonetheless enduresUnfortunately, no magazine would publish the haiku. The novelist has printed it on note cards, which she can be found giving away to passers-by in our town park, where she is also known sometimes to sleep, except when the police, whose thuggish tactics she so neatly parodied in her original manuscript, bring her in on charges of vagrancy. I have a copy of the haiku pinned above my desk, its note card grimy and furred along the edges from multiple profferings, and I read it frequently, sometimes with pity but always with awe.

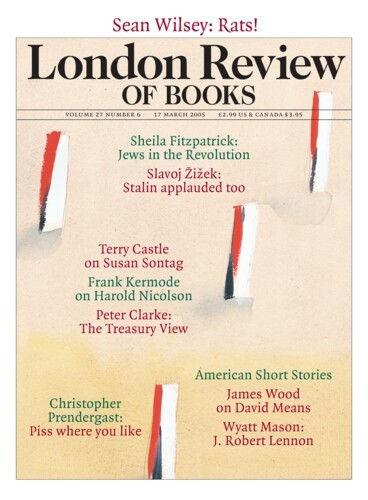

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.