Ma Jian wrote The Noodle Maker in 1990, four years after he left China for Hong Kong, then still a British colony. When Hong Kong was handed over to China in 1997, he left for Europe, living first in Germany, and later moving to London. Red Dust, the English translation of his memoir about three years’ wandering in remote parts of China, was published in 2001. On the back of Red Dust, Ma Jian is described as a ‘dissident artist’. In a recent interview in the Observer, Ma was again called an ‘acclaimed dissident’. Like the first Chinese Nobel laureate in literature, Gao Xingjian, who is routinely labelled ‘a veteran exiled Chinese dissident novelist and playwright’, Ma belongs to a group of Chinese writers living abroad who express anti-Communist opinions. Most of them are now in exile by choice – Ma is free to travel to China – but their political identity is intimately connected to their writing. Many, though not all, are activists who lend their voices to political organisations. ‘Dissidence’ has an obvious appeal, but is Ma’s writing any good?

I was 16 in 1987 when he published his novella ‘Showing Your Tongue, or Emptiness’ in People’s Literature, the pre-eminent state-run literary journal, and can vividly recall how shocked I was by the intentionally repugnant sex scenes and the gruesome depiction of violence. But I was also thrilled by its originality: it was radical in both its subject-matter (life in Tibet) and its manner (realistic and savage), which set it apart from dreary state-approved literature. (At the time, like many young people, I read the newly translated work of Western writers, such as Kafka and Dostoevsky, and ignored most of what was promoted by the state.) Ma’s novella strained the tolerance of the cultural bureaucracy; his work was condemned for ‘distorting and misrepresenting the lives of Tibetan people, which humiliates and angers Tibetans’. The editor in chief of People’s Literature was denounced for publishing the piece. Ma was already in Hong Kong by then.

The Noodle Maker consists of nine stories. The first two, ‘The Professional Writer’ and ‘The Professional Blood Donor’, introduce the two main characters and the novel’s frame narrative. In his shabby high-rise apartment in an unnamed provincial city, a middle-aged writer of official propaganda spends an evening talking with an old friend, a professional blood donor. The writer is depressed by his commission from the Party – a novel about a selfless soldier who is dedicated to the Communist cause – even though writing the book will give him the chance to be included in The Great Dictionary of Chinese Writers. The blood donor, on the other hand, is content with his marginal existence, selling his blood to hospitals for money and various sought-after material goods; he has even set up a blood donor agency.

Over a greasy roast goose and a bottle of booze, the writer and the blood donor swap banter, insults and confessions. Finally, the writer is ready to talk about the book he really wants to write. He ‘racks his brain, trying to think of someone he knows who shows the same selfless, heroic qualities’ as the soldier he is supposed to write about:

but all that comes to mind are the characters of his unwritten novel: a young entrepreneur who runs a private crematorium; an illegal migrant who writes letters for the illiterate; a father who spends his life trying to get rid of his retarded daughter . . .

These are people he knows, has read about or sees every day on the streets. They are the people he understands, the people he’d write about, if he had the courage. Their lives are as miserable and constricted as his own. But he is fully aware that if he wrote about these sad and feeble characters, his leaders would consider him unfit for the post of professional writer.

The rest of the novel is a series of stories from the writer’s unwritten book. The writer and his friend appear intermittently, increasingly drunk and increasingly shrewd, to comment on the characters and their ill-fated lives. Besides those anticipated by the writer in the passage above, there are also stories about a despairing actress who commits suicide in public; a middle-aged editor who has frighteningly sadistic love affairs in response to the humiliations he endures in his marriage; a young woman in the town’s Cultural Propaganda Department who is driven insane by the viciousness of her female co-workers; and a three-legged talking dog who observes life in a totalitarian state from a roof terrace overlooking a busy crossroad.

Ma is an inventive and talented storyteller, but his prose is unfortunately still rooted in ‘Mao Discourse’ (mao-ti), the coercive rhetoric of the Mao era that once was the only acceptable literary style: mao-ti is resolutely pedestrian, apart from its hyperbolic political vocabulary. Ma rebels against this oppressive legacy by overusing obscene language, especially when he writes about sex and women’s bodies (‘sensing a sour dampness seep from her lower body’ etc), which would have been prohibited in Mao’s time. This is a technique shared by many writers (mostly male) who want to find a new language to replace the old Communist one, but it invariably leads only to an obsession with the repulsive. Flora Drew’s translation of The Noodle Maker is more graceful than the original, lacking the self-conscious rudeness of the Chinese and the uneasy kinship with Maoist style.

The Nobel citation in 2000 described Gao Xingjian’s novel One Man’s Bible as a book ‘settling the score with the terrifying insanity usually referred to as China’s Cultural Revolution’. It makes you wonder what the writer was rewarded for: his literary merits or his political message. The blurb for The Noodle Maker promises ‘a virtuoso piece of "red humour” – a darkly funny novel about the absurdities and cruelties of life in modern China’. Is the novel another exposé of the evils of a Communist society? Is it one more book in a long line of publications, from Wild Swans to The Good Women of China, which are read and celebrated mainly for their political and historical significance? Perhaps. Yet The Noodle Maker often has qualities that go beyond its political message. The story, recently published in the New Yorker, of a father who tries to abandon his retarded daughter but ends up being her only protector is more than just an indictment of the One Child Policy.

Since there is little indication in the novel of when the long evening of intense talking takes place, readers are likely to assume it’s set now (it doesn’t help that nowhere in the book are we told that the Chinese original was published ten years ago). But anyone familiar with contemporary Chinese history will recognise that the stories are of the mid and late 1980s, a decade or so after the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). This is not a trivial detail. China has gone through huge transformations in the past fifteen years. A few years into the 1990s, the propaganda role assigned to the writer in Ma’s novel was largely a thing of the past; readers were buying romantic novels, self-help books and lifestyle magazines. Nowadays, any number of books on the ills of the Cultural Revolution are gathering dust in bookshops, along with avant-garde works that elicit little interest among book-buyers. There have been fewer and fewer literary/ political controversies, as people are no longer interested in literature as a way to achieve freedom; now there is a thriving capitalism to attend to. The sentiments expressed by the writer and his blood donor friend – distrust of the state, resentment of its thought control, helplessness in the hands of the Party – make sense only in their historical context. The writer ‘knows that his life is almost entirely devoted to the Party. But he has no idea who the Party is. He knows that the Party was around before he was born, and has controlled him his entire life. Every part of him belongs to the Party.’ This was a common enough feeling during the Cultural Revolution, but it had begun to fade by the mid-1980s, when the state started to allow private entrepreneurship and cultural interaction with the West.

But perhaps this is treating Ma as more of a social realist than he is. After all, ‘The Swooner’ is about a crematorium manager who pushes his own mother into the oven, and ‘The Carefree Hound, or The Witness’ is about a well-read talking dog. The young funeral manager settles old scores by cursing and kicking the corpses, and before wheeling his mother into the furnace, he watches her ‘scuttling between the corpses like a cockroach’. It comes as no surprise that Gogol is one of the authors the professional writer in The Noodle Maker admires, along with Gorky and Hans Andersen.

Belinsky called Gogol ‘the founder of the natural school’. But Rozanov wrote in 1906 that Gogol ‘looked on life with a dead glance and saw only dead souls in it. He by no means reflected reality in his works, but only drew a series of caricatures on it with amazing mastery.’ Is Ma’s fiction an accurate depiction of contemporary China? Or is he giving us caricatures because he looks on life with a dead glance and can see only dead souls around him? Belinsky, Robert Jackson wrote in Dialogues with Dostoevsky, ‘well understood that Gogol’s mirror was crooked. But Russian reality, Russian man, in Belinsky’s view, was in the profoundest sense unformed, grotesque, disfigured.’ Ma perceives his characters and their world in a similar way. When the funeral manager is about to push his mother into the oven, the narrator remarks:

In the old woman’s face, these eyes now looked gentle and kind. That expression has disappeared from today’s world. You can walk the streets for ten years and never find an expression like it. (At least you won’t find it on Chinese faces. Perhaps Western faces can look gentle, calm, kind. But in China, not only have those expressions disappeared, but so have all similar expressions of pity, compassion and respect.)

Ma seems to believe that only such exaggerations can reveal the flaws in Chinese society. Non-Chinese readers, however, unfamiliar with the range of the possible in contemporary China, might not always be able to distinguish the fantastic in Ma’s fiction from the actual, or the realistic. The intriguing combination of realism and surrealism is further complicated by Ma’s political agenda, which doesn’t always work in his stories’ favour.

One of the strongest is ‘The Suicide, or The Actress’. Su Yun, a former star of revolutionary opera, is now a stage actress about to pass her prime:

The winds brought in by the Open Door Policy blew away those revolutionary heroines, and Su Yun lost her way. She tried to keep up with the changing times and relax her moral views, but was kicked back time and again by a series of failed love affairs. She slowly lost her grip on reality and retreated inside herself. She wanted to travel to the core of her being, to see what lay at her life’s end.

What she sees in ‘the core of her being’ is a desire to die: not any death, but a brilliant performance on stage, with an audience witnessing her final glory. She writes a play about a woman with love problems who feeds herself to a tiger. The play itself is expertly, and often hilariously, inserted into the flow of the story:

The female lead should wear one of the chiffon nightgowns criticised in the latest Open Door Policy memorandum. If the club’s Party secretary permits, the top three buttons can be left undone and the sleeves rolled up a little. Deal with this matter in accordance with current levels of reform.

The story captures the confused cultural landscape of the late 1980s well. There was plenty of Communist propaganda left over from the Cultural Revolution, but ‘high-culture fever’ was also beginning – the mass production of and obsession with Western books and ideas. Su Yun reads Kundera and Heidegger. Trying to find a theatre for her suicide show, she phones the Open Door Club, ‘a venue filled with the type of liberal-minded people who had appeared since the launch of the reform policy’: ‘In the coffee bar, one could also exchange lithium batteries for Marlboro cigarettes, a bottle of foreign wine for a bicycle, a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover for the second volume of the erotic classic, Jin Ping Mei.’ Just before she dies, through the blood on her face, Su Yun sees one of her lovers sitting among the horrified audience, which gives her great satisfaction.

On cue, the writer and the blood donor reappear in the story, having finished their dinner but still drinking. They both knew the woman well; in fact, they once fought with each other over her affections. But the story then takes an overtly political turn. ‘Corruption and secrecy have become the only laws in this country,’ one of them says. ‘You could never keep to those laws,’ the other replies. ‘You just shut yourself up here, living in fear, blaming everyone else for your troubles. You would never dare jump into the thick of things and try to change your life, or to strive by any means possible to save yourself.’ And his friend replies: ‘The law only protects those in power. The rest of us are doomed to play the victim.’ This is an awkward way to end. The discussion about the law and corruption has little to do with Su Yun, who dies as much out of existential despair as anything else. The political statement threatens to reduce the story to anti-totalitarian propaganda.

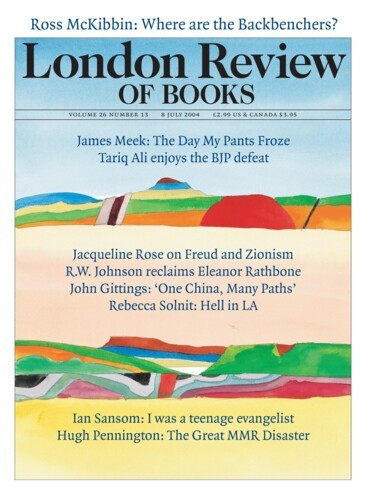

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.