The Paris-Madrid road race of 1903 was a wonderfully disgraceful affair. Three hundred cars set out, conferring death and dismemberment along the dust-choked roads south. Six of the drivers were killed outright and nearly twice as many gravely injured. The hospitals were stuffed with mangled sightseers. By the time the surviving drivers reached Bordeaux the race was called off, and in Madrid the garlanded welcome arches were quietly dismantled. One of the drivers taking part was Ettore Bugatti, the young Italian car designer, heir to a factory estate in Alsace. Among the spectators, probably, was three-year-old Hélène Delangle, destined to become one of his crack drivers. She would have been among the villagers of Aunay-sous-Auneau who thronged to see Louis Renault descending a nearby hill at 140 kph.

City-to-city road racing was now over. However, the dawn of motoring was still one of those dawns in which it was bliss to be alive. That same decade ushered in the Gabriel horn: ‘Everywhere you are greeted by the clear sweet note of the finest motor horn in the world.’ Or there was the Autoclear, ‘the horn with the three-mile note, yet mellow and inoffensive in tone’. What better way of alerting the sleepy cattle drover three miles ahead? The dust clouds raised by cars were still asphyxiating, but macadam was slowly bringing relief. Controlling a car became simpler, no longer a question (as a pioneer motorist complained) of doing two things with the left hand, four things with the right, and sometimes all of these things at once. But with improved design was rekindled the passion for speed; road racing might be illegal but the solo ‘speed merchants’ were getting away with it. That early Lanchester which ‘sang like a six-inch shell across the Sussex Downs’ contained (in the back seat) Rudyard Kipling, a bit of a road-hog who had the nerve to proclaim that the car had at last brought a major blood sport to Britain. His fellow poet and road-hog, John Masefield, also exulted as he traversed the Downs at furious speed, his Overland emitting ‘soul-animating strains’ (doubtless from a Gabriel horn). And the man who wrote to the motoring press urging drivers not to stop after an accident if they had a lady on board was Bernard Shaw.

Speed worship began to infect hard-headed urban councils, as one town after another (and not just in Britain) began holding Grand Prix round-the-houses races, or even round-the-houses-and-into-the-trees races. And what sort of landowner would refuse to play host to a concours d’élégance at which owners of magnificent chariots – Lagondas, Delages, Rolls-Royces – could admire each other’s turnout? And truly magnificent some of these thoroughbreds were; Roland Barthes thought cars ‘almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals, the supreme creation of an era’ (which might have been better said of the splendid ocean liners of the day). In the highest class came the Bugatti Royale, a car for rajahs and emperors (though the last Habsburg emperor went into exile in a Gräf und Stift, the Austrian Rolls, the same model in which the Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated at Sarajevo). But the Bugatti that made the name of Hélène Delangle, by then calling herself Hellé Nice, was the sports model, a lean, rakish and most elegant racer which made a noise often compared to that of tearing calico, or a mainsail splitting in a gale. That was only one reason why young men coveted it.

Hélène Delangle, a postmaster’s daughter, was a sprightly blue-eyed blonde who left the stifling environment of Aunay for a more exciting life in Paris. She had an ear-to-ear gamine grin and a good figure, and photographed well. It was inevitable that she should take to the stage and she appeared in ballet, revue, circuses and striptease, as well as giving private performances. A fetching photograph shows her, naked, holding aloft a fluttering dove, though it is not clear whether she was one of those dove dancers who summoned up a trained flock to take protective stations. Money flowed in. Fast women attracted fast cars, and vice versa; Hellé mingled, easily and promiscuously, with the rich, well-born motor-racing set. In 1927 she was at the Montlhéry race track, that glorified ‘Wall of Death’ near Paris, where Henri de Courcelles, a war-time fighter pilot of high distinction, was the first of her lovers to be killed at the wheel. A ski accident two years later ended her dancing career, but at once she switched to racing. There had been plenty of mettlesome, even feminine-looking women drivers before Hellé began making headlines. In The Bugatti Queen Miranda Seymour informs us that Violette Morris, an athlete and racing driver, had her heavy breasts removed because they interfered with her driving a Donnet.

In 1929 Hellé, driving an Omega-Six, won the Grand Prix Féminin at Montlhéry, becoming ‘the fastest woman in the world’ by lapping the steep-sided bowl at 198 kph. Her preparation for the race had been less than ideal: ‘A green-eyed boy, a friend of one of the costume makers at the casino, had stayed the night. A mixture of morphine, champagne and sex had left her wanting to crawl into a coal hole when she woke up.’ The morphine sounds ominous, but it was presumably to alleviate the ski injury. In an instant she found herself famous. No hangover could prevent ‘the charming Casino de Paris dancer’ from milking the victor’s applause to the limit, with time off to prick the blisters raised on her hands by the hot hammering of the steering wheel. Her prowess in the Omega brought an invitation from Ettore Bugatti to join his dwindling stable of women drivers. She was summoned to the Bugatti estate at Molsheim, ‘which all French Bugatti drivers looked on as their Camelot’, but significantly was not invited to stay under the family roof or even to dine there, being put up in the firm’s hostellerie, ‘Le Pur Sang’ (the Bugatti slogan). Ettore probably knew an adventuress when he saw one. He had a son, Jean, whom he expected to inherit the business and who had already been caught up in her circle.

Hellé Nice was not tied exclusively to Bugatti. In 1930 she undertook an extraordinary barnstorming tour of America’s dirt-tracks, velodromes, wooden bowls and other killing grounds. Mainly she drove America’s approximation to the Bugatti, a Miller, sometimes a Duesenberg, playing up to the crowd brilliantly and relishing her motorcycle escorts. The fans knew her as Hellish Nice. In homage to a driver whose car had dived over the edge of one of these tracks, she drove up to the spot, ripped off her scarf and tossed it down like a wreath. This went down well with the crowd, but it was an insane feat. An errant scarf had already strangled Isadora Duncan in her Amilcar on the Promenade des Anglais at Nice.

Then it was back to driving for Bugatti, or Alfa Romeo, or any other firm that showed interest in a driver ready to do handstands on the bonnets of its victorious cars. For her own conveyance she bought an opulent Hispano-Suiza, hideously expensive to run. But money flowed in. She endorsed Lucky Strike cigarettes and Esso; and if the cash flow faltered she was never short of rich friends. ‘The list of lovers,’ Seymour writes, ‘aristocratic and otherwise, who became involved with Hellé Nice during the 1930s is almost as long as the list of races in which she took part.’ The index divides them into ‘lovers’ and ‘brief affairs/ close friends’. In the former category, besides Henri de Courcelles, are Count Bruno d’Harcourt, killed racing at Casablanca, and Philippe Rothschild, the vineyard owner; in the latter are Jean Bugatti, killed in one of his own cars, a Spanish count and a Romanian prince.

In 1936 – a black year for Hellé Nice and motor racing in general – she was co-driver in the Monte Carlo Rally, starting from Tallinn with ‘a headlong rush along the glassy roads of Estonia, black ice all the way . . . the women drove as if possessed.’ Summer found her in Brazil, taking the wheel of an Alfa Romeo Monza in the ill-organised São Paolo Grand Prix. Rounding a corner at 150 kph she was faced with a bale on the track and a policeman trying to remove it: ‘A body flew up cartwheeling through a cloud of dust. The car jerked, spun and flung another body up, high over the screaming crowd, before it smashed into the jostling line of spectators . . . They went down like reeds to a scythe.’ Hellé was laid out with the dead but recovered after three days in a coma. Acquitted of responsibility for the disaster, she received generous compensation. ‘I killed a poor man with my head, and his death saved my life. I broke his skull,’ she said. That same year eight spectators were killed by a swerving Riley in the Irish Tourist Trophy Race. Another casualty was a descendant of Charles II, the young Duke of Grafton, burned to death in his Bugatti at the Limerick Grand Prix.

The São Paolo crash did not quench Hellé’s racing ambitions. She was much impressed by the powerful cars – Mercedes and Auto-Union – coming out of Nazi Germany and tried to get taken on as a works driver for Adler. One of her new ‘brief affairs’ was with a womanising SS officer who looked like Bertie Wooster: a bad move. What she did in France during the German occupation is a mystery, as Seymour is the first to admit. ‘I have never been in any trouble, civil or military,’ Hellé protested after the war. ‘Her collaboration,’ Seymour suggests, ‘if she was guilty of it, might only have taken the pragmatic form of being on good terms with the occupiers.’ She no longer had the Hispano-Suiza, unlike Sacha Guitry, who hung on to his throughout the war, and much good it did him. Ettore Bugatti hid his Bugatti Royale in his castle at Ermenonville. Hellé’s funds were running out, but in 1943 she left Paris with her most durable lover to settle into a newly built villa of ‘some considerable splendour’ at Nice. Could it have been an expropriated Jewish home? How close was she to that Nazi Wooster and his ilk? Seymour voices the obvious suspicions, but is reluctant to press them.

It was left to a fellow Bugatti driver, and a dashingly famous one, to destroy her reputation. In 1949 the Monegasque Louis Chiron spied her at a ball in Monte Carlo where that year’s Rally drivers were being fêted. In a loud voice he denounced her as a Gestapo agent: ‘Votre place n’est pas ici, vous.’ Hellé was too shocked to react: this was not one of those situations that could be met with a broad grin and a handstand. It was hardly worth suing him in the Monaco courts, since he was a hero in the principality and had powerful influence there, and French law did not apply. If he ever withdrew his charge he seems not to have done so publicly. Hellé did not retire immediately from racing, but her story now was one of betrayal, impoverishment and obscurity.

Seymour makes clear at the outset that much of the background to her story, in the absence of hard facts, is speculative. She was lucky enough, or persevering enough, to locate caches of Hellé’s photographs and cuttings, and to get access to letters, but the book is a ‘quest’ rather than a biography. In New Jersey she was able to sit in the car in which Hellé beat the world record in 1929. ‘I didn’t expect the Bugatti to be so pretty; I hadn’t, until I drove one, fast, understood the exquisite, adrenalin-filled rush it would bring, a feeling of exhilaration, of excited, dangerous joy. Few experiences could match the intense happiness of racing in a car like this.’ Where, and in whose car, she experienced this epiphany does not emerge.

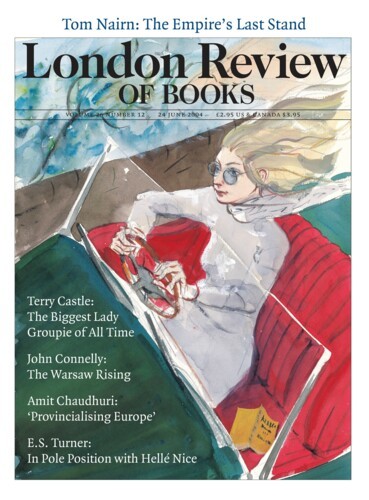

So what was Hellé Nice really like – an overgrown tomboy or a femme fatale? As a jolly sports girl she would have given John Betjeman a few – perhaps welcome – surprises. If it is hard to see her as a bit of a Mata Hari – and one would rather not – it is even harder to believe that she was a keen stamp collector, holding on to her albums to the end. In Britain she was never a household name. A visit to Brooklands in 1921 had taught her that women drivers were not wanted there. No doubt she could have handled one of those big green Bentleys with aplomb (Ettore Bugatti said the Bentley was ‘the fastest lorry in the world’). But, household name or not, Hellé Nice makes an ideal gamy centrepiece for Seymour’s spirited evocation of the sporting 1930s, a raffish and blood-boltered scene perhaps, but at least a change from seeing the decade automatically and unglamorously linked with Auden, Isherwood and Spender. Motor racing held all too many of us in its grip. I was sufficiently hooked to look in at the 24-hour race at Le Mans and the rather seedier, spectator-unfriendly event on the Newtonards circuit in Northern Ireland. Both visits were disillusioning. Brooklands boasted ‘The Right Crowd and No Crowding’, but many a race meeting was more like the one featured in Vile Bodies, where the wrong crowd overrun the hotels of a greedy and banner-infested town, its buildings barricaded as if against an enemy. What of the dashing drivers? ‘There were Speed Kings of all nationalities, unimposing men mostly with small moustaches and apprehensive eyes; they were reading the forecasts in the morning papers and eating what might (and in some cases did) prove to be their last meal on earth.’ I should have liked to hear Waugh on the Monte Carlo Rally competitors, whom occasionally I saw checking into their luxury hotels. The newspapers hailed as heroes these exhibitionists who (like Hellé and her partner in Estonia) drove ‘as if possessed’ over ice, black or white, ‘running out of road’ all over Europe, sometimes crashing on top of each other, even ditching within a mile of starting; and all this while local tradesmen in their vans negotiated wintry roads without spreading mayhem. The organisers always protested that this was a rally, not a race. Perhaps the organisers of the Paris-Madrid race should have billed it as a rally.

How would Hellé Nice and the Bugatti crowd have relished the motor-racing scene today? Though they were used to speeding under and through mazes of advertising, they did not cover every centimetre of their persons and their cars with brand-names. Also their cars looked like cars and not smoothing irons. It is odd that today’s strange vehicles should bear a close resemblance to those seen by a scornful poet at London’s Rotten Row a couple of generations earlier:

Cars flat as fish and fleet as birds,

Low-bodied and high-speeded,

Go on their belly like the Snake

And eat the dust as he did.

Flat as fish? Could G.K. Chesterton unknowingly have been enjoying a vision of the future?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.