John Charles Robinson , perhaps the greatest connoisseur Britain has ever known, was turned down on four occasions for the post of director of the National Gallery. He was thought to be too closely associated with the trade (‘little better than a dealer’), and was known to have operated with scant respect for officialdom when employed by the South Kensington museum. In addition, his taste deviated too far from the orthodox, as was most clearly demonstrated by his great enthusiasm – already developed by the 1860s – for the obscure Spanish painter El Greco. Sir Henry Layard, the trustee most vehemently opposed to Robinson, considered El Greco to be a ‘clever, but eccentric and rather repulsive painter’ whose best works ‘show a strange mixture of powerful, though frequently false, colouring and execrable drawing’. In 1867 Robinson tried in vain to sell an important El Greco to the gallery. In May 1895, not long after Layard died, he offered the Expulsion of the Traders from the Temple, justly observing to the new director, Sir Edward Poynter, that ‘it is very much above the average of this most eccentric master’s works and has the advantage of being in splendid condition.’ It is striking that ‘eccentric’ was the adjective employed by both detractor and defender.

Visitors to the exhibition at the National Gallery until 23 May may find it worth trying to understand why El Greco’s colouring once seemed ‘false’ and his drawing ‘execrable’. A good place to start is the Adoration of the Shepherds lent by the Metropolitan Museum, New York (where the exhibition opened last October). The foremost of the shepherds kneeling on the left is wearing a green jacket, and is placed in front of one with a yellow jacket. The yellow jacket, however, seems to jump in front of the green one. And then the white shirt of a third, more distant shepherd jumps in front of the yellow. Thus colour operates in opposition to the spatial logic of the picture. The composition has something of the fluttering instability of flames. Not only are figures elongated and distorted, but solid and void are confused: the head of the ox may strike us at first as the space beside the foremost shepherd and the infant Christ. And the black of the foreground shadows is continuous with the black background and also with a black outline which is neither foreground nor background.

A few decades ago it was fashionable to doubt whether El Greco really had been trained as a ‘Byzantine’ artist in Crete, but since then his signature has been discovered on an icon in a church on the Aegean island of Syros – number one in the exhibition. If we ask ourselves what prompted his departure from this style, part of the answer can be found in the household inventories of 16th-century Venice, in which the word ‘Greco’ constantly recurs. Many, perhaps most residences included at least one work of art in the Greek (that is, the Byzantine) style. Paintings of this sort were not, it seems, segregated from other types of picture, and the artists who made them were interested in adopting at least some Italian conventions – it is significant that fashionable Italian frames were used for some of these works (as can be seen from several examples in the museum attached to San Giorgio dei Greci in Venice). El Greco simply went further than his colleagues. By 1568, when he is recorded as being in Venice, he was especially attracted by the paintings of Tintoretto. His crimson, emerald, violet and lapis drapery with its flashy lights is extremely close to Tintoretto’s. But El Greco’s figures crowd together; their arms, even when outflung, tend to be absorbed into a complex surface pattern; and the marble architectural settings with their converging perspectives are just backdrops. In short, he was unable to assimilate the spatial dimension of Tintoretto’s art – the way his figures fly, thrust, hurtle or topple towards or away from us.

Once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his own – one that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting. Obviously his portraits involved precise observation, but the settings tend to be spectral. The city of Toledo is carefully recorded, but it rests on hills which have no more substance than the clouds above. In its essentials this style was still Venetian. Colour is used in a way that was made possible by Titian in his later work: it seems to float on the surface of El Greco’s paintings, only half connected with the material world. And his combination of the graceful figural distortions of Parmigianino with brushwork and paint which are designed to be appreciated partly for their own sakes was a formula first devised by Andrea Schiavone, who was fashionable in Venice when El Greco first arrived there.

The principal essay in the exhibition catalogue, by David Davies, is concerned to emphasise El Greco’s debt to the Counter-Reformation and to Spain. It explains how his subject-matter reflected the priorities of the Council of Trent – which is true of every artist working for Catholic patrons at that date – and, more interestingly, tries to relate the artist’s style to a strand of Neoplatonic theology: ‘using abstraction and avoiding literal illusionism, the artist diverts the mind to the spiritual essence.’ El Greco, Davies claims, made it clear that ‘his heavenly figures are not members of the material world.’ Yet the humble shepherds who clearly belong to the material world are painted in the same way as his angels. A more important objection is that Catholic Neoplatonism doesn’t account for the Italian equivalents and sources of his style. Much impressive information is supplied about the ardent faith and philosophical leanings of El Greco’s circle in Toledo, but nothing precise in the way of art theory is adduced and there is no mention of the fact that Catholic reformers who are documented as taking an interest in art rejected those tendencies in Italian painting by which El Greco had been inspired. Toledo may have been ‘pullulating with convents’. It certainly provided abundant patronage. But perhaps its great advantage for El Greco was that in artistic matters it was provincial and had no idea how eccentric his art had become.

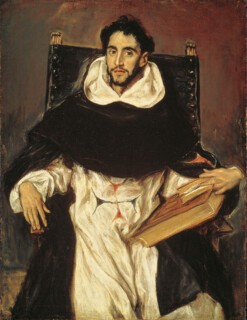

In the exhibition we can forget such speculations and concentrate on the qualities we are least able to appreciate in reproduction. Chief among them is the effect of the ruddy brown preliminary layer employed in his Spanish paintings. In the view of Toledo this smoulders below, and occasionally breaks through, the blacks, the green and stone grey of the hills, and the blue and white of the sky. And it is vital to his even more austere colour scheme in the great portrait of Paravicino lent by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The warm colour, which is only partly covered by the smokey background, can be sensed below the black and white habit and the ascetic pallor of the flesh, so that it seems as if the small areas of deep red – the jagged line at the meeting of the lips, the thin bars of the red cross like bloodstains on the garments – have broken through. The group of portraits in the exhibition is especially impressive, but in no other instance is the personality of the sitter so pervasive: Paravicino’s fingertips have as much nervous energy as his face, and the unstable chair he sits on and the precarious volumes he holds reinforce the extraordinary tension of the image.

The exhibition is just the right size. We appreciate seeing several variations on the same theme and are not too aware of the frequency with which El Greco repeated gestures and expressions and some of the shriller colour combinations. But, even so, the excitement of his handling fails after a while to compensate for the rather slackly articulated bodies, so loosely woven together. The crucified Christ of the 1580s in the Louvre is an exception. The pale body stands out against the dark sky, which absorbs the solidity of the cross itself, while the clouds mimic torn garments. It recalls the beautiful bronze crucifixes by the great sculptor Giambologna and as we follow the contours we realise that this is a type of drawing rarely found in El Greco’s work: three-dimensional form is clearly defined, even if it is at the same time given an unearthly grace.

In later works, such as the Met’s Adoration of the Shepherds, lines are often merely the ragged and smudgy edges which come about when one colour has been worked with stiff bristles or rubbed on (or off) with a soft cloth. From close to, there is no definition, merely a nervous interaction, and often enough the compositions retain a dynamic instability, not only in the preliminary sketches for large altarpieces but also in the reductions made afterwards (categories which are difficult to sort out, but both of which are well represented in this exhibition).

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.