Realism is one of the most elusive of artistic terms. ‘Unrealistic’, for example, is not necessarily the same as ‘non-realist’. You can have a work of art which is non-realist in the sense of being non-representational, yet which paints a convincing picture of the world. Conversely, Jeffrey Archer’s novels are representational but unconvincing. Jane Austen’s novels are realist, but you could claim that the spooky Gothic fiction she disliked so much reflects more of the anxiety and agitation of an Age of Revolution than Mansfield Park does. Life can be a good deal more surreal than André Breton. Walter Benjamin considered that Baudelaire’s poetry reflected the urban masses of Paris, even though those masses are nowhere actually present in his work.

Bertolt Brecht thought that realism was a matter of a work’s effects, not of whether it recalled something familiar. According to this theory, realism is a relationship between the artwork and its audience, in which case your play can be realistic on Monday but not on Thursday. One person’s realism is another’s fantasy. Realism is as realism does. Verisimilitude – showing a dockyard on stage, say – is not necessarily realistic in a politically and artistically evaluative sense of the word. Realism, in this view, is a matter of what the audience or readers get out of the thing, not what you put into it. ‘If one wanted an aesthetic,’ Brecht writes, ‘one could find one here.’

If realism is taken to mean ‘represents the world as it actually is’, then there is plenty of room for wrangling over what counts in this respect. You cannot decide whether a work is realist simply by inspecting it. Suppose we discovered a piece of writing from some long-vanished civilisation which we knew was in some sense fictional, and which paid inordinate attention to the length of men’s noses. We might categorise the work as non-realist, until further archaeological research revealed that the civilisation in question regarded nose-size as an important index of male fertility. In which case the text might shift into the category of realism. Literary critics in the distant future would not be able to tell that Endgame was non-realist unless, for example, they had historical evidence that putting old people in dustbins was not standard geriatric practice in the mid-20th century.

Artistic realism, then, cannot mean ‘represents the world as it is’, but rather ‘represents it in accordance with conventional real-life modes of representing it’. But there are a variety of such modes in any culture, and ‘in accordance with’ conceals a multitude of problems. We cannot compare an artistic representation with how the world is, since how the world is is itself a matter of representation. We can only compare artistic representations with non-artistic ones, a distinction which can itself be a little shaky.

Besides, representationalism has its limits. If the source of representing is the self, it is doubtful whether the self can be captured within its own view of the world, any more than the eye can be an object in its own field of vision. In picturing the world, the self risks falling outside the frame of its own representations. It is the dynamic power behind the whole process, but one which it is hard to figure there. The human subject becomes the blindspot at the centre of the picture, the absent cause of the world’s coming to presence. For the Modernists, this is a problem which is resolvable only by irony – by representing and pointing to the limits of your representation in the same gesture.

What, in any case, is so precious about an art which portrays life as it is? Why do we take delight in an image of a pork chop which looks exactly like a pork chop? No doubt we admire the skill which is needed for such acts of mimesis, but it is hard to feel that this is the whole story. Nor is it easy to see why Zola and the Naturalists thought that telling it like it was, taking the lid off the social underworld and exposing its squalor, was somehow inherently subversive. Behind this may lie the assumption that people in the overworld are as conservative as they are only because they don’t know about the sordid lives which others are forced to lead, which is far too charitable a view of them.

Isn’t it bad enough that everyday existence is bounded by laws and conventions, without art feeling that it has to follow suit? Isn’t part of the point of art to give those tiresome restrictions the slip, creating things such as the Gorgon, or a grin without a cat, which do not exist in nature? Realism is meant to be a riposte to magic and mystery, but it may well be a prime example of them. Perhaps the roots of our admiration for resemblance, mirroring and doubling lie in some very early ceremony of correspondence between human beings and their recalcitrant surroundings. In that case, what Erich Auerbach takes in his great study Mimesis to be the most mature form of art may actually be the most regressive.

To describe something as realist is to acknowledge that it is not the real thing. We call false teeth realistic, but not the Foreign Office. If a representation were to be wholly at one with what it depicts, it would cease to be a representation. A poet who managed to make his or her words ‘become’ the fruit they describe would be a greengrocer. No representation, one might say, without separation. Words are certainly as real as pineapples, but this is precisely the reason they cannot be pineapples. The most they can do is create what Henry James called the ‘air of reality’ of pineapples. In this sense, all realist art is a kind of con trick – a fact that is most obvious when the artist includes details that are redundant to the narrative (the precise tint and curve of a moustache, let us say) simply to signal: ‘This is realism.’ In such art, no waistcoat is colourless, no way of walking is without its idiosyncrasy, no visage without its memorable features. Realism is calculated contingency.

‘Reality changes,’ Brecht remarked, and ‘in order to represent it, modes of representation must also change.’ In this sense, a lot of Postmodern art is as realist in its own way as Stendhal or Tolstoy. It is faithful to a world of surfaces, random sensations and schizoid human subjects. Postmodernism takes off when we come to realise that reality itself is now a kind of fiction, a matter of image, virtual wealth, fabricated personalities, media-driven events, political spectaculars and the spin-doctor as artist. Instead of art reflecting life, life has aligned itself with art. In portraying itself, then, art ends up miming reality.

Like ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, ‘realism’ is a term which hovers between fact and value, the descriptive and the normative. It can be either a neutral comment or a glowing commendation. Georg Lukács believed that it was both at once: for him, a work of art which was realist in a descriptive sense was also aesthetically superior. Realism in this Lukácsian or Hegelian sense means more than simple representation, as well as more than ‘actually effective’. It means an art which penetrates through the appearances of social life to grasp their inner dynamics and dialectical interrelations. It is thus the equivalent in the artistic realm of philosophical realism, for which true knowledge is knowledge of the underlying mechanism of things.

Lukács’s sense of realism, then, is cognitive and evaluative together. The more a work of art succeeds in laying bare the hidden forces of history, the finer it will be. In fact, there is a sense in which this kind of art is more real than reality itself, since by bringing out its inner structure it reveals what is most essential about it. Reality, being a messy, imperfect sort of affair, quite often fails to live up to our expectations of it, as when it allowed Robert Maxwell to slip quietly into the ocean rather than ending up in the dock. Austen or Dickens would never have tolerated such a botched finale. For the Lukácsian case about realism, technique is an optional extra, like having a stereo or a sunroof in your car. It is his or her position in history which allows a writer to see into the heart of things, not talent or a way with words. This fails to account for the fact that Balzac is a realist, but not every realist is Balzac. It also fails to account for the writer who has an excellent grasp of historical dynamics, no sense of verbal rhythm and a vocabulary of only two hundred words.

Lukács never doubts that realism in this ‘deep’ sense goes hand in hand with realism as representation. But there is no reason to assume a logical link between the two, as Brecht, the Futurists and the Surrealists recognised. Why cannot montage or automatic writing or the alienation effect achieve the same cognitive end? Anyway, is art really just second-hand cognition? Marxism is philosophically speaking a realism, but it does not follow from this that its aesthetics have to be realist too, either in the Lukácsian or the representational sense of the word. For the various Modernist and avant-garde Marxist artists of the early 20th century, the whole point was to overthrow existing representations, complicit as they were with the dominant political power. Indeed, they wanted to overthrow the act of representation itself, partly because it was not clear how you could ‘represent’ a reality which was changing and contradictory without striking it dead in the process. How do you take a snapshot of a contradiction?

The avant-garde Leftists also found something sinisterly consoling in representational realism, which reassures us with images of a world we feel at home with. Bernard Shaw’s plays may be radical in their content, but their stage directions portray a world so solid, familiar and well-upholstered, all the way down to the level of the whisky in the decanter on the sideboard, that it is hard to imagine ever being able to change it. In this sense, the realist form usurps the radical content. Besides, representational art is from one viewpoint the least realist of all, since it is strictly speaking impossible. Nobody can tell it like it is without editing and angling as they go along. Otherwise the book or painting would simply merge into the world. No sooner had the English novel embarked on its celebrated rise in the 18th century than Laurence Sterne reminded his literary colleagues of the crazed hubris of the realist project. Determined not to cheat the reader by leaving anything out, Tristram Shandy represents so much material so painstakingly that its narrative collapses. Indeed, the novel form itself is an impossible contradiction, since it is committed at once to representation and formal design, two ends which, in our society at least, are ultimately incompatible. You cannot marry everyone happily off in the last ten pages and claim that this is how life is.

Realism, then, can be a technical, formal, epistemological or ontological affair. It can also be a historical term, describing the most enduring artistic mode of the modern age. It is the kind of art most congenial to the ascendant bourgeoisie, with its relish for the sensuously material, its impatience with the formal and ceremonial, its insatiable curiosity about the self and robust faith in historical progress. Perhaps it is impossible for us now to re-create the alarming or exhilarating effect of a few pages of Daniel Defoe on an 18th-century reader reared on a literary diet of epic, pastoral and elegy. The idea that everyday life is dramatically enthralling, that it is fascinating simply in its boundless humdrum detail, is one of the great revolutionary conceptions in human history, which Charles Taylor in Sources of the Self claims as Christian in inspiration. The modern equivalent of Moll Flanders in this respect is EastEnders.

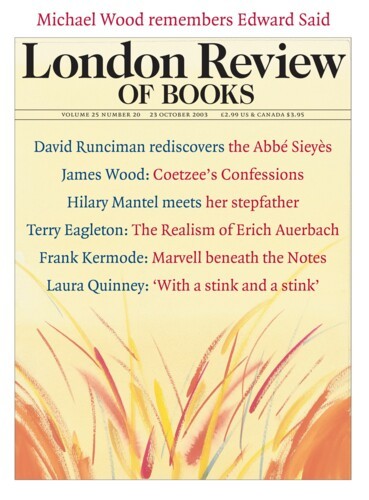

Auerbach’s Mimesis, one of the great works of literary scholarship, was written between 1942 and 1945 in Istanbul, where Auerbach, a Berlin Jew, had taken refuge from the Nazis. The book was published in 1946, and this new edition, with an introduction by Edward Said, marks the 50th anniversary of its first appearance in the United States. Auerbach ranges through some of the mighty monuments of Western literature, from Homer, medieval romance, Dante and Rabelais to Montaigne, Cervantes, Goethe, Stendhal and a good many authors besides, scanning their work for symptoms of realism. His criterion for selection, however, is more political than formal or epistemological. The question is whether we can find secreted in the language of a particular text the bustling, workaday life of the common people. For Auerbach as for Mikhail Bakhtin, who was writing his classic work on Rabelais and realism at much the same time that Auerbach was holed up almost bereft of books in Istanbul, realism is in the broadest sense a matter of the vernacular. It is the artistic word for a warm-hearted populist humanism. It is thus an anti-Fascist poetics, rather as for Bakhtin it was an anti-Stalinist one. Mimesis is among other things its author’s response to those who drove him into exile, even if they were unlikely to have heard of Farinata and Cavalcante or Frate Alberto.

For all its formidable erudition, then, there is a fairly simple opposition at work in Mimesis, one more class-based and militant than the universal respect paid to Auerbach by conservative scholars would intimate. Realism is the artistic form that takes the life of the common people with supreme seriousness, in contrast to an ancient or neoclassical art which is static, hierarchical, dehistoricised, elevated, idealist and socially exclusive. In Walter Benjamin’s terms, it is an art which destroys the aura. There is an implied continuity in this respect between Homeric epic and the Third Reich, with its heroic myths, tragic posturing and spurious sublimity. If all this had been argued by a Trotskyist English lecturer at a redbrick English university, rather than by one of the 20th century’s most eminent Romance philologists, it would almost certainly have provoked a clutch of dyspeptic reviews in the learned journals. If you can make such claims in a dozen or so different languages, however, as Auerbach doubtless could, and if like him you know your French heroic epic from your Middle High German one, you are likely to win a more sympathetic hearing.

Like Lukács, then, Auerbach uses ‘realism’ as a value term. Like Lukács, too, he is a Hegelian historicist for whom the art that matters is one flushed with the dynamic forces of its age. Neither critic can find much value in Modernism: Mimesis ends by rapping Virginia Woolf sternly over the knuckles, while Lukács can see little but decadence in Musil and Joyce. The upbeat humanism of both men is affronted by the downbeat outlook of the Modernists. Both are doctrinal life-affirmers, high European humanists dismayed by the flaccid melancholia of the late bourgeois world. Unlike the austerely disembodied Hungarian, however, Auerbach is a radical populist who celebrates the fleshly and mundane, a man for whom authentic art has its roots ‘in the depths of the workaday world and its men and women’. If realism is bourgeois for Lukács, it is plebeian for Auerbach. In this respect, Auerbach is a curious cross between Lukács and Bakhtin, blending the historicism of the former with the iconoclasm of the latter.

Authors score high marks in Mimesis for being vulgar, vigorous, dynamic, grotesque, demotic and historical, and are ticked off for portraying characters as stylised, idealised, non-evolving, psychologically stereotyped and free of context. The book’s celebrated opening chapter, ‘Odysseus’ Scar’, one of the great set-pieces of literary criticism, contrasts what Auerbach sees as Homer’s externalised presentation of things, which fixes them in space and time and knows only foreground, with the Old Testament’s more concrete, commonplace, historical, socially mixed view of the world. There can be no serious treatment of the common people in the culture of antiquity, whereas the New Testament grants a fisherman like Peter psychologically complex, potentially tragic status. Antiquity, unlike modern realism, has no conception of historical forces.

Similar contrasts can be found in the literature of the Middle Ages. The French heroic epic is rigid, narrow and simplified, whereas medieval religious drama is redolent of the ‘everyday and the real’. The acme of world realism arrives with the Divine Comedy, whose elevated style can integrate the vulgar, humdrum, grotesque and repulsive in a language which Auerbach, a Dante scholar of great distinction, regards as ‘a well-nigh incomprehensible miracle’. Dante transports an earthly historicity into his heaven and hell, in an idiom which is both sublime and sublunary. Shakespeare interweaves high and low with equal adroitness, though marks are deducted from his work for failing to take the common people seriously enough. (English literature in general takes a back seat in Auerbach’s work – strangely, given the demotic flavour of much of its major realism.) As for Cervantes, his ‘gaiety in the portrayal of everyday reality’ has never been equalled. Goethe’s work, by contrast, fails to represent the inner dynamics of a revolutionary age, retreating instead into an aristocracy of the spirit.

Behind this realist mingling of styles lies the influence of Christianity. It is in the Christian gospel, for which God incarnates himself in the humble and destitute, that the affinity between what St Bernard calls ‘sublimitas’ and ‘humilitas’ is first established. Christianity, with its parody of a Messiah and carnivalesque reversals of rich and poor, shatters the classical equipoise between high and low. What lies behind realism is Revelation. Auerbach might have quoted Matthew 25 here, which has the Son of Man coming again to judge the living and the dead, depicted in some off-the-peg Old Testament imagery of angels and clouds of glory. But the effect is calculatedly bathetic, since it turns out that what saves or condemns you is such embarrassingly quotidian matters as whether you fed the hungry and visited the sick. Salvation, for the Judaeo-Christian tradition, is an ethical and political affair, not a cultic one.

Mimesis turns on one of the most momentous cultural events of human history: the morally and artistically serious representation of unvarnished everyday life, as the common people enter the literary arena long before they make their collective appearance on the political stage. Rather as Roland Barthes once speculated that one could write a history of textuality, showing how the self-conscious play of the signifier threads its way through the history of writing, so Auerbach charts the surfacing and submerging of popular realism from Homer to Woolf. Precisely because of this coming and going, there is no unbroken teleology at work here, but there is certainly a presumption that an art which smacks of the common people is ethically and aesthetically superior to one which does not.

Rigidly interpreted, this would elevate A Taste of Honey over Phèdre. There is no reason to assume that an art attuned to the common life will be politically radical, any more than the common people themselves are spontaneously radical. William Empson revealed the ‘progressive’ possibilities of as well-bred a genre as pastoral. Neither is it true, as romantic populists like Auerbach and Bakhtin tend to believe, that everyday life is somehow more ‘real’ than courts and country houses. Cucumber sandwiches are no less ontologically solid than pie and beans. Nor is there anything inherently valuable about dynamism and mutability, as Auerbach seems to assume. Capitalism is the most dynamic social system history has ever witnessed, and a touch of stasis would do it no harm at all. Mingling styles is sometimes subversive and sometimes not. There is no more enthusiastic mingler than the market.

Auerbach’s championing of realism over antiquity also involves backing it against Modernism. Those for whom all valid literary characters are well-rounded, psychologically complex creatures are unlikely to be impressed by the wasted protagonists of Samuel Beckett. Indeed, the prejudice against ‘stereotypes’ and in favour of subtle, plausible, full-blooded characters is one of the most entrenched in our current literary orthodoxy, which is no doubt one reason the most favoured form of literary narrative in Britain is biography. It is a remarkably narrow view of literature, excluding an enormous number of intriguing fictional figures, from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, the witches in Macbeth and Milton’s God to Swift’s Gulliver and Dickens’s Fagin. Some literary characters are meant to be freaks, caricatures, emblems or plot functions, whatever the dogmatic humanists may consider.

Whereas a literary scholar today might take, say, 1830 to 1900 as his or her specialist period, Auerbach’s period stretches for almost three thousand years. Anglo-Saxon scholars sometimes like to console themselves for their poor showing in this respect by claiming that high European humanists like Auerbach deal in oracular generalities, whereas they themselves grapple with the material detail of a text. Mimesis is a discomforting work for such self-apologists. For Auerbach’s method, like that of his great philological colleague Leo Spitzer, is to fasten with fastidious sensitivity on some stray phrase or passage in order to unpack from it a wealth of historical insight. It is his combination of scholarly erudition and critical astuteness which is most remarkable, not least in an age when those who know all about books are rarely the sharpest analysts of them, and vice versa.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.