Before Picasso, it is impossible to think of a major European artist of more protean character than Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). By 1580 he had established a high reputation in Haarlem for miniature portraits in which sensitive faces, soft beards and crisp ruffs are drawn in metalpoint or engraved – in one case engraved in gold – with delicate precision. It is hard to believe that they are the work of the same artist who, a decade later in Italy, made large, bold portraits in coloured chalks of himself, his dog and his new friends. But the style of Goltzius’s work is determined not only by the date he made it or the medium he employed, but by its subject matter. He widened the gap between art as observation and as invention. And in the splendid exhibition of his drawings, prints and paintings at the Toledo Museum of Art until 4 January we are more often in the company of gods, heroes and personifications with small heads, large thighs and remarkably elastic anatomy, than among portraits or specimens of natural history (the John Dory, a monkey, a dromedary).

Having established the distinction between Olympian poetry and quotidian prose, he obtained startling effects by allowing elements of one mode to cross into another: he gave his antique heroes the huge moustaches of contemporary beer-swilling soldiery and his goddesses the latest court coiffure. With Goltzius, burlesque increased in importance in the visual arts, although we can’t be quite sure of the extent to which this was intended.

In the mid-1580s he began to translate into prints, and then to imitate in his own inventions, the figure style of the Emperor Rudolf’s Court artist, Bartholomeus Spranger, which involved not only bizarre proportions and dizzy facial expressions but strange movements – human helicopters with outflung limbs, outspread fingers and upturned big toes. But Goltzius was equally alert to the masters of the High Renaissance. He created a highly ambitious variation on the balletic movements in Marcantonio’s famous print of Raphael’s Massacre of the Innocents. He also studied the rugged style and rustic subjects of Titian’s woodcuts, and created compositions in which clouds and streams, mountain tracks and tree trunks are charged with, and united by, greater muscular energy than Titian himself had achieved. Among his last and greatest engravings are imitations of Dürer and Lucas van Leyden, imitations of both form and technique which are quite uncanny.

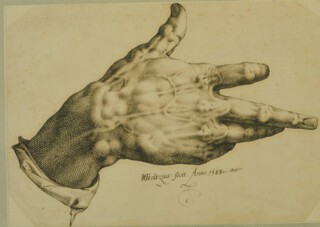

Even when Goltzius is not adopting another artist’s manner, appreciation of his art presupposes some knowledge of previous work with the same subject or in a similar style. He is the sort of artist that many modern academic art historians suppose all artists to have been. Goltzius is always a performer. And technically he is a virtuoso. The virtuosity Goltzius parades is that of the engraver who cuts lines with effort into a copper plate using a steel tool. The line can be straight or it can curve; it can even curve one way and then another. As pressure is released and the tool is withdrawn the line tapers; with increased pressure – and Goltzius was the first to exploit this effect to the full – it can swell. Freedom of drawing is no more possible in this medium than the body movements of an actor are compatible with ice-skating. But Goltzius made pen drawings in imitation of engravings – Goltzius’s Right Hand (1588), is an example. Some of these drawings are on large prepared canvases, as in the picture lent to the exhibition by the Philadelphia Museum of Art showing the goddess of love being awakened and warmed. The light on her flesh and the colour of lips and nipples and the flames of Cupid’s torch have been added in oil paint. Several great painters of the 16th century had been innovating printmakers, but Goltzius was a great printmaker who was also a painter and his most remarkable paintings were these large drawings which stole their beauty from engravings.

When we look at the engraving closely we follow lines racing around tight corners, next we notice shapes – diamonds – created where lines cross, then we watch how the net is stretched and the lines swell and break, or we peer into the darkness where net is thrown over net. In Goltzius’s sublime subjects, such as the gods creating heavenly spheres, or heroic victims tumbling into outer space, glassy transparency, smoky gloom, hints of infinity not only seem spun out of lines but these lines are hypnotically mind-bending. Paintings by Titian or his followers dissolve on close scrutiny into intuitive and improvised smudges and dashes: engravings by Goltzius shift into abstract patterns which reveal completely premeditated control. This is as evident in the catalogue,* which includes superb details of his prints and drawings, as it is in the exhibition. Justice is done to Goltzius. We can assess his astonishing range. But his limitations are also revealed.

Among his earliest work is a series of four engravings of the story of Lucretia. The first two depict social scenes – the noisy lamp-lit camp dinner and the quiet fireside wool-working – very effectively, but neither the scene of the rape nor that of the suicide is possible to take seriously. It remains true in his later works that dramatic encounter, indeed clear narrative action, is not a strength. Moreover, there are feelings that his figures never express. In the same series as his dazzling imitations of Dürer and Lucas van Leyden there is an attempt to imitate the greatest of his Italian contemporaries, Federico Barocci, but it doesn’t work, chiefly because what is meant for melting delight on the face of Joseph as he looks down on the infant Christ becomes a slightly mad grimace. A painting by Barocci of Saint Francis receiving the stigmata arrived at the Met while the Goltzius exhibition was there (it is the first autograph canvas painting by this great artist to enter a North American museum). It is so shocking in its expressive power that we forget the artist, forget to ask how this is achieved, or how the painting became possible. This is something we would never be likely to do in front of a Goltzius.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.