A revealing text for understanding the hold that Spanish painting of the 17th century had over the imagination of art-lovers in Britain and France during the first half of the 19th century is the description of the ancient Scottish seat of the Roman Catholic earls of Glenallan in Walter Scott’s The Antiquary. The late Countess, ‘partly from a haughty contempt of the times in which she lived, partly from her sense of family pride’, had not permitted the interiors to be modernised. The ‘valuable collection of pictures’, which hung in ‘massive frames . . . somewhat tarnished by time’, included ‘family portraits by Vandyke and other artists of eminence’, but was richest ‘in the Saints and Martyrdoms of Domenichino, Velázquez and Murillo’ – and the ‘manner in which these awful, and sometimes disgusting, subjects were represented, harmonised with the gloomy state of the apartments’. Beyond the picture gallery was the Earl’s private chamber, its high walls hung with black mourning cloth. ‘Two lamps wrought in silver’ shed an ‘unpleasant and doubtful light’ on a silver crucifix and ‘one or two clasped parchment books’. ‘The only ornament on the walls was a large picture, exquisitely painted by Spagnoletto,’ of the martyrdom of St Stephen.

The Spanish school evoked the rack, the rapier, the ruff, the spiral ebony chair-leg and the fainting nun, and a world that was now sufficiently distant or in decline (in The Antiquary it is the invasion of Bonaparte, not the Jacobites, for which beacons are prepared) to appeal to the imagination of a more enlightened age. Scott must have chosen Domenichino because his name conjured up, to anyone of taste, a painting that had long been one of the most admired in Rome and was familiar from prints and copies even to those who had not travelled there: the Last Communion of Saint Jerome, a quintessentially Counter-Reformation subject.

The other artists listed are Spanish. Murillo was chiefly known for his paintings of two great themes in art: the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, and picturesque poverty, the former filled with smiling cherubs, the latter featuring grinning urchins. Spagnoletto was the artist we now know by the name of Ribera, who was active in Naples, then under Spanish rule; he was associated with paintings that depicted the sufferings of emaciated saints and the eloquence of beggar philosophers: an appropriate reference for Scott, not only because of the faith of the ‘gaunt and ghastly’ Earl, but because Edie Ochiltree, the King’s beadsman, an itinerant sage of proud bearing and wild white hair who encounters the Earl in his private chamber, might also have been a fit subject for Ribera’s brush.

What Scott and his readers would have thought of as a typical painting by Velázquez is less clear, as we shall see, but he was well known as the portraitist of a sombre King, his solemn counsellors, chaperoned princesses, dwarfs and jesters. He too painted the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception and the ancient sage in modern rags. The most beautiful of his paintings in the National Gallery shows a child conducted by an angel to view Christ, who, having been whipped, has collapsed on the prison paving. The child, as I explained to the late Princess Margaret on one of her visits to the Gallery, stands for the Christian soul. ‘How very, very Spanish,’ she pronounced slowly, after a moment or two pursing her lips.

The Antiquary was published in 1816, not long after the Allies had insisted that the French return to Spain the paintings they had confiscated for the Musée Napoléon in the Louvre. Major works (by Titian, Raphael and probably Van Eyck, as well as by Spanish artists) which had been illegally removed and found their way into private collections in London or Paris were not returned. And Marshal Soult was allowed to keep his many artistic trophies, among them Murillo’s great Immaculate Conception from the Hospital de los Venerables Sacerdotes in Seville, a picture that is known to have been on offer for 250,000 francs in 1823 and, ten years later, for twice that much. It was bought for 615,000 francs by the Louvre in the sale of 1852 which followed the Marshal’s death – then the highest price that had ever been paid for a painting.

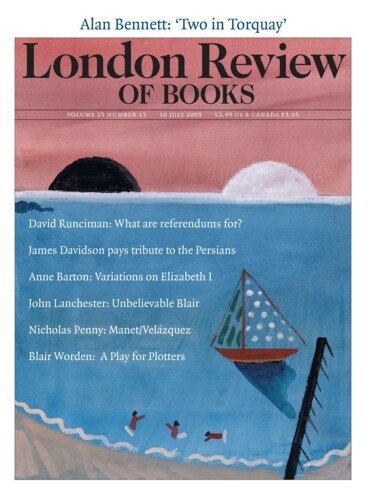

The exhibition Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting, which opened last year in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and went on to the Metropolitan Museum, New York, gave us a sample of the masterpieces in Soult’s collection and in the Galerie Espagnole in the Louvre, which was formed by Louis-Philippe partly out of that collection. In the Metropolitan Museum The Immaculate Conception was mounted on a special screen (on which it could not be hung as high as it should be) in the middle of a large room. The label concluded with a note that in 1940 the ‘French Government decided to return it to Spain’. This seemed rather coy for an exhibition that addressed the relationship between political power and artistic taste, and the catalogue entry, full of useful information, is also euphemistic on the nature of this transaction, ‘closely following the end of the Spanish Civil War’, and deftly avoids the words ‘Hitler’, ‘Vichy’, ‘Nazi’, ‘Falangist’ and ‘Franco’. Given this embarrassment the loan is a remarkable achievement.

Although an important aim of the exhibition was to explore the influence of the Spanish Old Masters – and their successor Goya – on modern French painting, we quickly realise that Murillo, who was by far the most admired, and much the most expensive, of the Spanish artists whose work became more available as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, did not in fact exercise an influence on 19th-century painters such as we might expect. There is an occasional echo in Delacroix and Manet, but no painter paid homage to him in quite the way that Gainsborough had in the previous century. The great esteem for Murillo was, incidentally, no less strong in Britain than in France, and the most beautiful Murillos in North America – Abraham and the Three Angels in the Canadian National Gallery and the Return of the Prodigal Son in the National Gallery of Art in Washington (the former loaned to the exhibition in New York) – were sold by Soult to the second Duke of Sutherland in 1835, and hung for more than a century in the magnificent gallery of Stafford House (now Lancaster House). Architectural recesses were specially designed for them, crowned by medallion portraits of the artist, and they were surrounded by a court of smaller Spanish paintings.

The apotheosis of Murillo in London and Paris called attention, by way of a reaction, to the genius of Velázquez, which could only be appreciated in the Prado (the museum opened in 1819). When Gautier wished to astonish readers of his account of Madrid in 1847 he declared that he rated Velázquez well above Murillo ‘despite all the tendresse and suavité of this Correggio of Seville’. As he made clear, of the great Spanish painters, Velázquez was the only one who, to be fully appreciated, had to be seen in Spain. Richard Ford, in his Handbook for Travellers in Spain, had made the same point two years earlier. He conceded that Murillo was more successful ‘in delineations of female beauty, the ideal, and holy subjects’, but Velázquez’s ‘representation of texture, air and individual identity are absolutely startling’ and he is ‘by far the greatest painter of the so-called naturalist school’.

High praise for Velázquez was not entirely new. In 1786 Reynolds described his portrait of Pope Innocent X as ‘one of the first portraits in the world’ – he had seen it more than thirty years earlier in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome, where it is still to be seen today. In this exhibition it is represented by a copy by Amédée Ternante-Lemaire made in 1846, which is of interest because it is full of pentiments (revisions that become visible as the paint becomes more transparent with age). Such pentiments are often taken as proof that a painting is the original, since a copyist would not normally have any reason to change a composition. But the fascination of Velázquez’s handling lies in the fact that it is both ‘free and firm’ and, as Ford put it, he moves ‘directly to the point’. This can only be imitated by a copyist who dispenses with the usual patient diligence. Reynolds’s pupil James Northcote described to Hazlitt ‘a whole-length portrait by Velázquez, that seemed done while the colours were yet wet; every thing was touched in, as it were, by a wish; there was such a power that it thrilled through your whole frame.’

Reynolds was inspired by Velázquez – by the vivid recollection of one masterpiece. But there was, at the time, great confusion about Velázquez’s work. In the gallery of the duc d’Orléans in the Palais Royal, a collection admired by all art-lovers visiting Paris, there was a large Finding of Moses supposedly by Velázquez which was later acquired by the Earl of Carlisle for Castle Howard. It is mentioned briefly in the catalogue of this exhibition as by Honthorst, but it has long been recognised as a masterpiece by Orazio Gentileschi (and was recently exhibited as such at the Met). To understand how such a misattribution could have been made requires a huge effort of the imagination. Knowledge of Velázquez had certainly improved when Louis-Philippe, a descendant of the duc d’Orléans, opened his Galerie Espagnole in 1838, yet the large altarpiece of the Adoration of the Shepherds that was attributed to Velázquez there, and was acquired as such by the National Gallery in 1853, would never now be mistaken for a painting by him, although the peasants in the foreground with their leathery skin and clumsy hands are relatives of the rural folk who mingle with, and occasionally impersonate, classical deities or Christian saints in his earliest work. Eighteen other paintings in the Galerie Espagnole were attributed to Velázquez – ‘none unreservedly accepted today’.

Probably the most admired private collection in Europe in the 1840s and 1850s was that of comte James-Alexandre de Pourtalès-Gorgier, housed in the exquisite neo-Renaissance interiors of 7 rue Tronchet in Paris. For concentrated quality and luxurious ambience it resembled the Frick Collection today, but in the owner’s lifetime admission could be gained only by a letter of recommendation (such as was supplied by Count Sidonia in Disraeli’s novel Coningsby, where the collection is breathlessly described). After Pourtalès’s death it could be visited only on Wednesdays in the first four months of the year, and its prestige was further enhanced by the limited access. It was the superb male portrait by Antonello da Messina, the so-called Condottiere, acquired from this collection for the Louvre, which made him one of the most popular Renaissance artists. It was the pair of male portraits by Bronzino in this collection, the finest of his portraits ever to leave Italy (both are today in New York), which established his reputation as the greatest court portraitist of the 16th century. And it was the Pourtalès collection that made the radiant portrait by Frans Hals, later to be known as the ‘Laughing Cavalier’, more famous than any other picture by him. The contest between Lord Hertford and Baron James de Rothschild to buy it at the Pourtalès sale in 1865 made it even more so. But it is sobering to realise that the Dead Orlando, a picture of the youthful warrior in black silk, lying dead surrounded by skulls, was quite as famous as these works. The composition was evidently a moral allegory, because a lamp beside the warrior is expiring and soap bubbles float across the foreground. Very, very Spanish. Memorable, too – for its limited palette and rather startling composition – but not a great painting and certainly not by Velázquez. Yet it was then one of the artist’s most admired works and it too was purchased for the National Gallery. It has long been consigned to the Gallery’s lower floor but was cleaned for the present exhibition. Soon it will return to that fascinating graveyard of taste.

How could the director of the National Gallery, Sir Charles Eastlake, one of the most discerning connoisseurs in Europe, have made such a mistake? One answer would be that he had not spent enough time in Spain. But genuine work by Velázquez had been accumulating in Britain. The great full-length portrait of King Philip had long adorned the dining-room of Hamilton Palace, the nude Venus was in the Moritt collection at Rokeby Hall, the portrait of Camillo Massimi was at Kingston Lacy and the portrait of Juan de Pareja was at Longford Castle, to name only the outstanding examples. Just how little general awareness there was of this development is clear from the fascinating pamphlets published by John Snare, an antiquarian bookseller who was convinced that he had found Velázquez’s portrait of the future King Charles I of England, made in Madrid in 1623. In the course of legal action in 1851 concerning the ownership of the picture, London picture dealers testified that it might be worth more than five thousand pounds (Edinburgh dealers thought it worth about £15). The Waterseller in the Duke of Wellington’s collection and the Boar Hunt recently purchased for the National Gallery were cited by Snare in his pamphlets and by the expert witnesses at the trial, but none of the masterpieces hidden in country houses is mentioned.

Richard Ford alleged that Bonaparte’s generals ‘did not quite understand or appreciate’ Velázquez’s ‘excellence’, hence they removed few of his paintings. But by 1850 French officials were as keen to acquire works by Velázquez as their British equivalents. In that year a Portrait of a Monk that was believed to be by him was acquired for the Louvre. Numerous artists, including the young Manet, registered requests to copy it. Then, in the following year, the same museum bought the Réunion de portraits, a much acclaimed acquisition, of which Manet made a copy, probably later in the decade (both original and copy are in the exhibition). It was soon acknowledged that the Portrait of a Monk was not worthy of Velázquez and the Réunion was gradually recognised as a workshop piece. A little knowledge and great enthusiasm are an intoxicating mixture, feeding the delusions of a collector like John Snare, on the one hand, but also inspiring Manet to devise a new way of painting – and of escaping from the influence of Delacroix, Courbet and his own teacher, Couture.

Velázquez had something to do with the bold economy, the clean colours and the strong contrasts of Manet’s paintings in the early 1860s, but Manet painted those abrupt opaque shadows around the eye, dashed white into the wet black of a sleeve, swept pale, sandy grey around a dark jacket, and left the scarf and sash and flower half-defined (as if reluctant to let them cease to be primarily a patch of colour and a few rapid brush-strokes) before he went to the Prado and studied Velázquez properly in 1865. Of course, when he did so he was overwhelmed, but his interest in Spanish art declined soon afterwards. Perhaps he was shaken by his discovery that Velázquez’s representation of ‘texture, air and individuality’ was achieved with far less flamboyance of handling.

Several of Manet’s paintings amount to variations on themes by Spanish artists. Thoré described the Dead Toreador (1863-64) as an audacious ‘pastiche’ of the Dead Orlando. Baudelaire was to protest that Manet did not know the Pourtalès collection. But he could as easily have derived the striking simplicity of the composition and the distribution of black from a print. Certainly his Monk at Prayer (1864-65) recalled Zurbarán’s Saint Francis, then the most famous work by this artist, though Manet knew it only in reproduction since the original had been bought for the National Gallery in London more than a decade before, at Louis-Philippe’s sale.

As for The Tragic Actor (1865-66), it is a variation on Velázquez’s portrait of the jester Pablo de Valladolid in the Prado. Manet would have been astonished to find all three of these paintings hanging beside or near the Old Masters I have mentioned. There was no problem with the first pairing, but the Zurbarán made Manet’s monk look like a studio model. And even though Velázquez’s portrait had the disadvantage of being mottled with discoloured retouchings and covered with a yellow varnish (the effect made worse by a new varnish on top) it still made Manet’s actor seem stagy and the painting as a whole seem showy. Perhaps Manet’s actor’s pose, when studied in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, suggests ‘fierce inward passions’, as is claimed in the catalogue, but not here, where the right hand and the dangling left leg seemed not only poorly drawn but uncertain in purpose.

The exhibition also encouraged us to explore the relationships that other major French painters enjoyed with Spain. Delacroix’s small self-portrait of 1821 and a study for the old women in the foreground of his Massacre at Chios were hung on either side of Goya’s portrait dedicated to Ascensio Juliá. This is a brilliant combination of images which remains suggestive even after we have excavated from the massive catalogue the information that this Goya was not the one in the Galerie Espagnole, and was probably not known in France, and the observation that Delacroix’s portrait instead exhibits ‘some affinity’ with another painting – which may not be a genuine Goya and was not certainly known to Delacroix.

Then there is the case of Degas, who painted Pagans, a Spanish tenor, playing the guitar. There is nothing obviously Spanish about the way it is painted, but Gary Tinterow, co-organiser of the exhibition, makes the ingenious and original proposal that the varieties of finish and focus may owe something to the study of Velázquez’s ‘smudges’. The distrust of finality which was so fundamental to Degas, and which surely owed something to his troubled eyesight, also reflects a tension in an artist trained to define form in drawing but made aware by Velázquez that imprecision is a part of our optical experience and essential to some aesthetic experiences too. Tinterow also suggests plausibly that the influence of Las Meniñas is ‘palpably present’ in Degas’s portrait of Tissot, even though some of the compositional devices that he mentions (notably the pictures within the picture) can be found in earlier paintings by Degas.

The final room in the exhibition in New York was dominated by John Singer Sargent’s great square canvas of the four daughters (and two giant Chinese jars) of Edward Darley Boit. This, as has always been acknowledged, is a painting that owes its compositional ingenuity to the example of Las Meniñas, and Sargent’s brilliant small copy of that painting was hung conveniently nearby. Accidents of light and surprises in scale keep us alert as we scan the space from blurred detail in the foreground to the reflections in the shadowy distance. The pictorial suspense seems to arise from the circumstances of the portrait: the contrast between the trust, curiosity, reserve and withdrawal of the subjects; our sense that their divergent personalities are only precariously united, and can be at ease only briefly in this opulent but dark interior.

It is a subtle Jamesian painting (far more subtle than any Manet) but far less reserved than Velázquez. The whites framed with black, reds and blues leap out as those of Velázquez never do. Opposite were the paintings by Carolus-Duran which taught Sargent to value these electrifying contrasts. Beyond, on the far wall, was Sargent’s Dr Pozzi in his crimson dressing-gown, inevitably recalling Velázquez’s Innocent X yet completely different in effect. And beside Pozzi was Sargent’s Madame Gautreau, her white flesh half clad in black, with a predatory silhouette as compelling as those designed by Toulouse Lautrec for his posters.

Beside these portraits of Pozzi and Gautreau was Whistler’s Théodore Duret, which also belongs to the early 1880s, and his Cicely Alexander of the previous decade. It was a conjunction as unhappy as that of Turner and Claude in the National Gallery. Sargent’s force seems harsh and vulgar beside such delicacy, yet it succeeds in making the delicacy look timid and precious. We learn something from the dual fatality. Sargent’s artistic outlook was conditioned by the art exhibition, and Whistler’s by an aversion to it.

The recent exhibition felt like one that had grown too large, and in this last room we could have done without the earnest portraits by Eakins – so laboured in this company – or Mary Cassatt’s bland smiling bullfighters. But there is one American painter whose absence is to be regretted. George Bellows gave to the handling of Manet and Sargent a novel slap and punch which suited the violence and velocity of New York. We forget, among all the high society in this last room, that the Spanish Old Masters had also been drawn to rags and deformity. Bellows gave the guttersnipe Paddy Flannigan the menace of Ribera – a quality imitated by Ribot, some of whose exquisite but disturbing paintings were included in the show, but absent from Manet’s urban wildlife – and in the distorted faces around the boxing ring he recaptured the terrifying, phantasmagorical realism of Goya. It would have been good to end an exhibition in New York with a painter who learned from Spanish artists to do justice to this great modern metropolis.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.