Charles Clarke’s reservations about the usefulness of studying classics were more or less on a par with the old schoolboy assertion that ‘Latin’s a dead language,/As dead as dead can be:/First it killed the Romans,/And now it’s killing me.’ The Education Secretary was, unsurprisingly, sharply criticised; not least by Peter Jones, a Spectator columnist, who told the BBC that ‘a calm, reasoned and balanced judgment would put it down to pig ignorance and blind prejudice’ – open-eyed prejudice being, I suppose, more to his taste. This is too harsh. What Clarke said was that ‘education for its own sake is a bit dodgy’ – he is head, after all, of the Department not only for Education but also, crucially, for Skills – and that while he’d be sorry to see philosophy go from curricula, he’s ‘less occupied by classics’. But I imagine that, if he thought about it, he’d see that classics is capable of producing skilful citizens. Studying Latin or Ancient Greek, at least as much as any other academic subject, improves the way you think. Besides which, it enables you to read, for example, Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Sappho, Sophocles, Euclid, Hippocrates, Archimedes, Lucretius, Seneca, Livy, Tacitus, Virgil, Ovid, not to mention Descartes: for all sorts of reasons, I wouldn’t want to live in a world in which no one understood them.

And I don’t suppose Charles Clarke would, either. But there’s more to classics than the study of grammar and syntax, ancient history and philosophy: Latin and Greek are taught principally, overwhelmingly, in private schools – and this, I suspect, gets to the heart of Clarke’s distrust. It’s unfortunate, then, that he won’t say anything against, or do anything about, private education. (The Spectator would of course scoff, but its disapproval would then be, as it should be, something he could be proud of.) Never mind the huge barrier to educational equality and progress that private schools represent: let’s ignore that, and instead thoughtlessly talk about the ‘dodginess’ of reading Plato. For that is the Third Way.

Trying to second-guess the workings of the minds of others is a dangerous business, however. Who am I to speculate about members of the Cabinet in this way? After all, I’m not a professional, unlike Jerrold Post, the director of the political psychology programme at George Washington University. Post studied at Yale and Harvard Medical School, before working for the CIA for more than two decades, setting up their Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behaviour. A book edited by Post is due next month: The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders, with Profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton (Michigan, £21.50). Quite what those two have in common, beyond being the bêtes noires of the American Right, beats me, but there it is. Anyway, the publishers have sent out Jerrold’s own chapter on Saddam as a taster, from which we learn that the tyrant had an unhappy childhood, and that while he ‘is not psychotic, he has a strong paranoid orientation’. He also suffers from ‘malignant narcissism’. So far, so what. But the really disturbing stuff comes at the end:

Saddam has found that international crises are helpful to him in retaining power in his country . . . when Saddam is backed into a corner, his customary prudence and judgment are apt to falter. On these occasions he can be dangerous to the extreme – violently lashing out with all resources at his disposal. The persistent calls for regime change may well be moving him into that dangerous ‘back against the wall’ posture.

Disturbing, if not particularly surprising; and certainly not a case for war. ‘Of one thing we can be sure,’ Post concludes, ‘this is a man who “will not go gentle into that good night”, but will “rage, rage against the dying of the light”.’ I don’t think unleashing mayhem on the grand scale was quite what Dylan Thomas had in mind. For a more fitting refrain, we could do worse than look to Cato the Elder: Carthago delenda est (repeat ad nauseam).

Send Letters To:

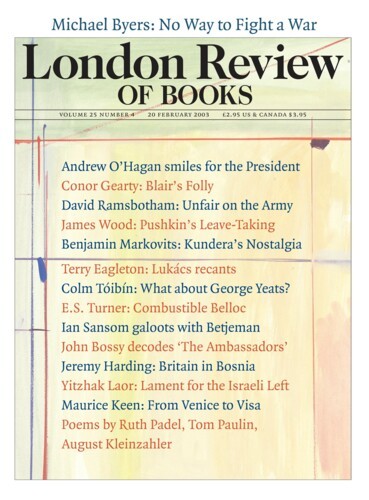

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.