Though Le Havre lies close to the Normandy beaches, it hardly features in histories of D-Day and its aftermath. Blocked at Caen, the Allied armies broke through to the south, wheeled left and raced for Paris. By the end of August 1944 the capital had been secured and the Seine crossed at last. With hindsight it seems that Le Havre had lost any strategic significance it might have had, but it was still in German hands and it was decreed that RAF bombers should flatten the town. Five thousand died in the ensuing siege, three thousand on the night of 5 September. It was the greatest single French loss of the Second World War.

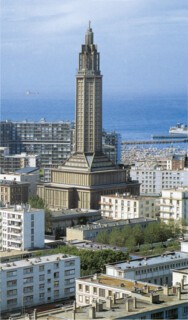

The transatlantic liners that once made Le Havre almost chic have gone, but the sea is still just about the only way to get there from London. On a moonlit winter evening, as the shore approaches, the town lays itself out beneath an electric halo, the Church of Saint-Joseph lifting its lighthouse-like campanile majestically behind. The ferry barges across the seafront for its dock with categoric straightness, welcome after the shambles and indirection of Portsmouth.

Night-time is right for exploring central Le Havre. Broad, grave and silent streets succeed or cut one another geometrically, their pavements and carriageways glistening wet in the lamplight. They are lined with immeubles – ‘walk-up’ blocks of flats, built to a common height and on a uniform structural grid. On the avenue Foch, the Champs Elysées of the reconstructed town, the boulevard gapes into emptiness. Pavement, slip road, grass verge, then an ampler pavement and even wider verge all precede the roadway itself, before the sequence runs in reverse. The discipline of Le Havre is inexorable. It is how the postwar Soviet city might have looked, had they got it right. And it is all, the morning reveals, made of concrete.

Behind the rebuilding of the city was France’s most famous architect of the time – not Le Corbusier, but Auguste Perret (1874-1954). And Perret’s career has been the subject of a handsome exhibition, shown recently in Le Havre and soon transferring to Turin and Paris.1

Even today, no major show on a 20th-century architect can escape a modicum of hype about the ‘Modernist project’. But from the Modernist perspective, Perret is an ambiguous figure. He made his name by uniting discipline in design with unswerving commitment to constructing in reinforced concrete. Concrete was already used for massive walls or wide spans, but in smart architecture it was hidden away behind masonry or a render. By dint of technical concentration, Perret transformed the material into an exposed and glorious art. The best place to see this is the wonderful church he built after the First World War at Le Raincy in the eastern Paris suburbs, as a memorial to the Marne victory that halted the German advance of 1914. Nicknamed the ‘Sainte Chapelle of reinforced concrete’, it is filled with stained glass by Maurice Denis and Marguerite Huré.

So far, so progressive. But Perret was also an unabashed upholder of French classical architecture. In temperament he was a dapper, worldly and dignified figure, fond of apophthegms – the architectural counterpart perhaps of Claudel, Gide or Valéry. In his projects of the 1930s, he refined the exposed frame into a new concrete classical ‘order’, intended as the updated standard for France’s tradition of monumental building. Perret saw the unruly experimentalism of Le Corbusier and other root-and-branch Modernists as distractions from the higher tasks of architecture. Though no Fascist, he also respected much of what Mussolini had built. By the time of the Second World War, he was a famous teacher and had a large following.

Perret was an architect-constructor, not a city-planner. But like any chip off the French classical block he had a weakness for monumental ensembles. His first essay in reconstruction was a new, formal square in front of the damaged station at Amiens. Then came the numbing obliteration of Le Havre. In the emotional days after Liberation, his pupils persuaded him to let them form the Atelier de reconstruction Auguste Perret around him.

The centre of Le Havre was not quite a tabula rasa. Most of what the British had wiped out was a town extension set out progressively in efficient squares, as the commercial port expanded. So the layout of Le Havre today consists of an adjusted plan not a new one, with streets widened, arcaded or straightened, but always marching to the bleak rhythm of the concrete-framed immeuble.

Most of Le Havre’s architecture is the work of members of the Atelier. Perret presided from Paris, coming to the coast on rare occasions only, and dying in 1954 when much had still to be done. The Cartesian unity of the town is due partly to stringent rules for reconstruction worked out under the Vichy Government, and partly to the discipline and spirit of the Perret team. Every block is different, and there are individual details to relish, like the downward tapering classical columns along the arcades of the rue de Paris. But everyone kept to the same module and much the same style. It was collective work, as most architecture must be, and none the worse for that.

If there is to be a single hero of the enterprise it ought not to be Perret but Jacques Tournant, now 93. Tournant represented the Atelier on the spot and managed the plan’s progress through every tortuous negotiation with municipality, proprietor and builder. Perret reserved two buildings for himself, and Tournant was his helpmeet on the defiantly classical Hôtel de Ville, sorting out a compromise between the mayor, who wanted stone, and the master-architect, who insisted on concrete. Perret endowed the Town Hall with a tower which Tournant contrived to refashion into an office block – a half-skyscraper for wielding authority over the Havrais.

But the tower that haunts the mind is that of Saint-Joseph, Perret’s memorial to the five thousand dead of 1944. Nothing in the church commemorates those events; indeed the only text in the town so much as to hint at them is a plaque appended to the overblown First World War memorial. The history of French architecture is littered with expiatory churches and chapels – projects not just about memory but about guilt and anger. The Sacré Coeur in Montmartre is the most famous. But Saint-Joseph, Le Havre is the most profound.

For thirty years Perret had been building and dreaming concrete churches which were to reconcile the French gothic and classical traditions. Here, at the climax of his career, the styles drop away entirely. Outside, Saint-Joseph is quite plain: an immense, octagonal grey phare or beacon set centrally over a square. It makes a telling landmark for seafarers, yet at over a hundred metres it is only a third of the height to which the fires of 1944 are said to have risen. Inside, raw piers of concrete thrust up from the corners and then lurch inwards to carry the open lantern which, you feel, must sooner or later come smashing down. Bare surfaces and a grille of tiny windows, tinged with rhythms of burning colour by Marguerite Huré, intensify the claustrophobia. Discouraged, the modern congregation now huddles behind a glass screen at the back. Perhaps this church was not meant for the living.

The Perret team did not have it all their own way in Le Havre. It was helpful to turn from the well-appointed Perret exhibition in the Musée Malraux, with its sleek architectural models crafted at state expense and its rhetoric about l’aventure de la modernité, to two fringe shows about the reconstruction. At the Musée du Prieuré de Graville, a screen-display focuses on the ville provisoire, the temporary town put together in haste after 1944 to house the thousands of homeless.2 Even here, as so often in architectural exhibitions, much is said about the various hut-types, but little about the experience of those who had to make do with them. The nicknames given to the hutments that the Havrais soon took over from occupying Americans, ‘Camp Philip Morris’, ‘Camp Weed’, say much about postwar priorities.

A third show, at the Musée de l’Ancien Havre, relates what happened to the port district, the Quartier Saint-François.3 A notoriously insanitary working-class area, it also contained many of the town’s most venerable houses. The quarter had already been evacuated and wired off by the Germans. As raids intensified, a local teacher was permitted to make a survey and the wartime Monuments Historiques listed some of the structures. It was spared the worst of the September 1944 bombardment. But a battle had then to be fought against the Perret plan, which threatened to raze almost everything. Finally it was agreed that the Quartier Saint-François should be ‘distinct’; the ubiquitous immeubles were allowed to have a brick facing and pitched roofs. The district lacks the punch of the Perret grid. But there are restaurants here, and children play in the streets.

On the ferry home, a Channel squall has blown up. The last sight of Le Havre, as the town recedes, is the stark phare of Saint-Joseph, lingering reproachfully until it merges with the weather.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.