Travellers to the western Polish city of Wroclaw in the 1980s could still encounter Germans who had lived there before the Second World War. One of those who escaped the mass exodus of the German population in 1945 was a man named Schiller, who had married a Polish woman and blended into local society without much comment. He seemed happy enough when I met him; and his Polish neighbours appeared remarkably incurious about and benevolent towards one of the last living links with their earlier history. Norman Davies and Roger Moorhouse probably never met Schiller, but he could be a character in their stimulating book, which recounts the history of his home town.

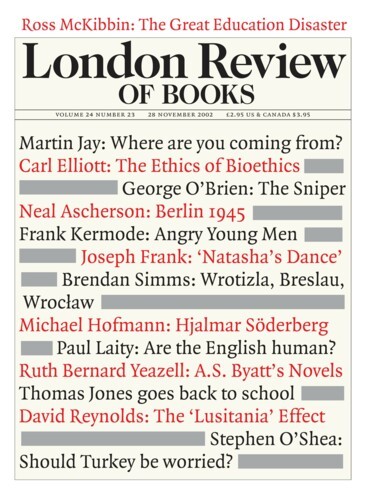

The name of the town itself does not appear in the title, and rightly so: language and appellation are never value-free. This is not mere historical correctness, but an attempt to understand each epoch of the city in its own right. For this reason, we are treated to more than a half a dozen different renderings in the chapter titles: ‘Island City’, for archaeology and prehistory, before AD 1000; ‘Wrotizla’ for the Polish-dominated High Middle Ages, from 1000 to 1335; ‘Vretslav’ for the period under the Bohemian Crown, from 1335 to 1526; ‘Presslaw’ for the Habsburg era, from 1526 to 1741; ‘Bresslau’ for the period of Prussian rule, from 1741 to 1871; ‘Breslau’ for the two chapters dealing with united Germany from 1871 to 1945; and finally ‘Wroclaw’, the name under which the city is now known – for the time being.

The connecting thread in this project is the concept of Central Europe and its multiple identities. To write the history of Breslau, Norman Davies says, is to reconstruct a ‘microcosm of Central Europe’, in which German colonisation, Slav reassertion, the Jewish experience, the various empires and the lethal ‘double dose’ of Nazi and Stalinist totalitarianism all find their place. One of the first people to use the term ‘Central Europe’ was Joseph Partsch, a professor of geography at Breslau and the author of Central Europe (1903), a volume in Sir Halford Mackinder’s famous series ‘The Regions of Europe’. Microcosm forms part of what Davies calls his own ‘longstanding efforts to overcome the artificial division of European history into East and West’. The authors dismiss the notion of ‘historic right’ as a ‘dubious fiction’. Instead, they demand that ‘old fixed nationalist archetypes must be rejected in favour of a shifting, multicultural kaleidoscope’.

As a result, this ambitious and demanding book takes in not only the entire sweep of German and Polish history, but at times also that of Central and Eastern Europe as a whole. The struggle for Breslau, it emerges, has been a contest between German and Pole; Habsburg and Hohenzollern; Hussite heretic and Catholic; Catholic and Lutheran; Jew and anti-semite; patrician and magnate; socialist and capitalist; Nazi and Soviet; apparatchik and dissident. And yet, as Davies and Moorhouse stress, this story was often as much one of co-operation and coexistence as of conflict and annihilation. Microcosm is not a short book, but the sheer extent of the years and changes it traverses justifies every line; it could even have been a little fuller towards the end.

The story begins with a dramatic dissonance: the siege of German Breslau by the Red Army. In a very short period of time, much of the city, which had escaped the Allied terror-bombing more or less unscathed, was flattened by Soviet artillery. Many of the surviving buildings were emptied by frantic German Entrümplungskommandos or ‘clearance details’, trying to create clear fields of fire for the defenders; huge swathes of the historic city centre were also levelled on the orders of the fanatic Gauleiter, Karl Hanke, so that he could build an air strip there to facilitate resupply and – as it transpired – his own escape. Hard on the heels of the victorious Red Army came advance Polish detachments, staking their claim to the city.

For the next forty years or so, the annexation was to be portrayed not only as rightful punishment for Nazi aggression but also, and primarily, as the natural reassertion of Polish sovereignty over ‘historic’ lands lost to Germanic colonisation in the Middle Ages. Yet, as Davies and Moorhouse make clear in their chapter on the prehistory and archaeology of Breslau, ‘the first settlers were not connected in any way with the Slavonic and Germanic peoples who would later dominate.’ Rather, they were Corded Warers, Lusatians, Jordanovians, Uneticians, Bylanians, Celts, Venedians, Scythians, Vandals, Goths, Huns, Gepids, Heruli, diverse Slavs and a number of other more or less recondite tribes: but for the shortage of evidence, the authors freely admit, this list would probably be even longer. The crucial point, they stress, is that ‘at each stage, the newcomers mixed and mingled, and ultimately obliterated their predecessors.’

The Polish claim to Silesia and its capital is based on association with the legendary Piast dynasty in the High Middle Ages. During this period, Wrotizla – named after the Polish bishopric founded in 1000 – was the largest town in what Davies and Moorhouse describe as a ‘fully integrated province of the Polish kingdom’; and with relatively short interruptions it has remained Polish in terms of Roman Catholic organisation until the present day. There is no doubt that Wrotizla was a town in every meaningful sense of the word well before the large scale settlement by Germans with their legal definitions of urban rights and status that so impressed generations of later historians. Yet if it was politically Polish, its ethnic character was much harder to determine, and Davies and Moorhouse warn against anachronism. Most of the inhabitants were certainly Slavs, and many were Polish speakers, but a majority may have been Czechs or Wends. There were also quite a few Jews, who at this time seem to have coexisted more or less happily with their Christian neighbours.

In 1327, Vretslav was inherited by the Bohemian Crown, becoming definitively part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. It was to remain within the broader German commonwealth for more than six hundred years. But in terms of cultural and ‘national’ identity, the picture was far more complicated, not least because many of the inhabitants spoke more than one language. The combination of Czech, German, Polish, Jewish and other influences made Jagiellonian Vretslav a ‘multi-ethnic city’; in so far as there was a common language it was Latin. Yet with diversity came increased conflict: the Jews were expelled in 1453, witches were persecuted, and in the early 15th century the Emperor Sigismund made Vretslav the base for his enthusiastic operations against Hussite Czech religious dissidents, who unsuccessfully besieged the city in 1428.

After the catastrophic battle against the Turks at Mohacs in 1526 and the death of Louis II Jagiellon, Presslaw passed to the Habsburgs, an Austrian dynasty that provided the German emperor more or less continuously until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Their arrival coincided with the impact of the Lutheran Reformation, which saw Presslaw become the most Protestant city in the Empire after Nuremberg, Bremen and Magdeburg. It is a tribute to the skill – or apathy – of the staunchly Catholic Habsburgs and their Protestant Lower Silesian subjects that the confessional divide never resulted in all-out war. It nearly did so at the beginning of the Thirty Years War, when Presslaw supported the forlorn ‘Winter King’, but the city managed to escape the Habsburg backlash and maintain a precarious neutrality for most of the rest of the conflict. At the concluding Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the right of free Protestant worship was reaffirmed. As Davies and Moorhouse demonstrate, confessional tension was to some degree eased by the ‘largely consensual nature of the Silesian Reformation’. Some churches even allowed Catholic Masses and Lutheran services to take turns on Sundays. As a result of this co-operative spirit, which was reinforced by the stalemate between the Habsburgs and Presslaw’s elites, the city was spared the worst ravages of the Counter-Reformation. Of course, toleration had its limits: Calvinist and Anabaptist sects were unwelcome, and Jews were still barred.

The Habsburg period was the decisive phase in the cultural Germanisation of the city. The Polish element – caught between the new, mainly German, Imperial administration and an increasingly ebullient German Protestant patriciate – was now distinctly embattled. It is true that local schoolmasters mostly went to study in Jagiellonian Cracow. But, as Davies and Moorhouse make clear, the ‘great majority of Vratislavians’ were ‘monolingual German speakers’. Only ‘tiny islands’ of Polish influence remained ‘in a cultural landscape of overwhelming Germanity’: ‘To all intents and purposes Habsburg Presslaw was a thoroughly German city.’ At the time, however, Vratslavians were more exercised by the religious divide. The impressive townhouses of Catholic Silesian magnate families such as the Dohnas, Hohenlohes and Hatzfelds were regarded by the established patriciate with a mixture of sourness and awe.

Despite its central location and various sieges, the city had so far changed hands only by inheritance. In 1740, however, Frederick the Great, using a shaky dynastic claim as his excuse, invaded Silesia and swiftly captured Bresslau. Now the boot was on the other foot, but the confessional balance remained largely unchanged: the Protestant Hohenzollerns not only tolerated Catholicism but actively courted the hierarchy, which they sought to keep out of the Habsburg orbit. Toleration was also extended to the Jews, who were readmitted, subject to conditions, in 1744 and by the late 19th century accounted for about 5 per cent of the population. The biggest change was the arrival of relatively efficient Prussian administration and the numerous unpopular exactions associated with Frederick’s wars, all fought to secure Silesia and its capital for the Hohenzollerns. Throughout the Prussian period Bresslau remained in the thick of things, as Davies and Moorhouse’s account of the Napoleonic period and the wars of Liberation, which were launched from the city in 1813, shows.

In the 19th century, Bresslau, or Breslau as it was increasingly called, experienced every variety of socio-economic modernisation: industrialisation, the arrival of the railways, municipal self-government, poverty, class conflict and, above all, huge population growth. German unification in 1871 did not change Breslau’s status – Silesia remained within Prussia, the largest federal state – but it did bring to the city national political conflicts such as the Kulturkampf between Bismarck and the Catholic hierarchy, which was bound to be exceptionally bitter in a confessionally divided province, and the fight against the Social Democrats, who rose inexorably to be the largest party in Breslau. The national question, by contrast, was much less acute than in Posen or Upper Silesia, where there were sizeable Polish populations, or even majorities. As one visitor observed in 1840, ‘Breslau is a thoroughly German city, the Poles are guests here’; and the Polish element was more and more on the defensive with every passing year.

With the rise of national consciousness, the Prussian and later the German Government abandoned more liberal dynastic policies in favour of rigorous Germanisation. But it was not all compulsion. Not only was Breslau already an overwhelmingly German city, but German identity had its attractions, comparable perhaps to the lure of Polonisation to Lithuanians and Ukrainians in the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The brashness, the technical superiority, the education, the municipal magnificience, the high culture, in short the sheer brute confidence of Imperial Breslau meant that ‘the forces of assimilation were unusually strong . . . The pot could be expected to melt its contents and to leave a much smaller residue than before.’ Among the beneficiaries of this process were Breslau’s increasingly integrated Jews, who constituted the third largest community in the Empire.

This confidence did not survive the First World War. Unlike Upper Silesia, which was bitterly contested, Breslau escaped direct involvement in the German-Polish struggle after 1918. But the shock of defeat and supposed betrayal poisoned politics and culture in the city, as elsewhere in Germany. The perceived failure of the Weimar Republic and the ravages of the Depression drove voters into the arms of the Nazis, who registered their third best national result in Breslau in the elections of July 1932. After Hitler’s takeover a year later, Breslauers were as quick as their compatriots elsewhere to look the other way as socialists, trade unionists, Communists and Jews were discriminated against, deported and eventually murdered. There were six forced labour and five concentration camps within Breslau or in its immediate vicinity. The city also served as a launchpad for the invasion of Poland in 1939. Of course, the ultimate retribution of siege, destruction and exile in 1945 was visited on all Breslauers equally: Nazis and surviving socialists, collaborators and resisters, young and old, men and women.

Microcosm is a remarkable book, whose authors demonstrate an admirable capacity for empathy: Norman Davies is a renowned Polonophile, yet no trace of Germanophobia disfigures the account. At the same time, they negotiate the many academic debates on Silesia in general and Breslau in particular with a light touch. The argument throughout is based either on their own research or on the most recent secondary literature. One omission is the very helpful volume on Wroclaw in the Polish Historic Towns Atlas, which was simultaneously published in 2001 in Polish and German under the aegis of the International Commission for the History of Towns; this seems to have appeared too late to be taken into account.

If there is a conceptual difficulty, it is that for most of its history Breslau was much less of a Central European microcosm than some of the other cities Davies mentions in the introduction. It was truly multicultural only during the Jagiellon period. Thereafter, it was palpably and increasingly a German city, and by 1900 less Polish than Berlin or the great industrial centres of the Ruhr. After 1945, Wroclaw was – pace Schiller – an entirely Polish city. This trajectory sets it apart from more truly microcosmic Central and Eastern European cities such as Prague, Vilnius, Lvov, late Habsburg Vienna, or smaller towns such as Paul Celan’s Czernowitz, which were more divided. In the same way, the Silesian magnates do not seem to have been ambiguous about nationality in the same way as their Czecho-German counterparts in Bohemia. When the Poles marched into Breslau in 1945, there was no sense of triumph comparable to that felt by the Czechs in Prague; the Poles themselves had never (seriously) claimed the city.

If many of the chapters lack something of the verve of Norman Davies’s earlier books, God’s Playground and Heart of Europe, which made him a hero in Poland, the last chapter, which deals with Polish Wroclaw from 1945 to the present day, does something to make up for this. It is vintage Davies, and controversial. The cruel treatment of surviving German civilians, not only by the Red Army and Polish Communists, but also by ordinary Poles, is depicted in terrible detail. The behaviour of some Jews – heavily over-represented in the security services – is roundly criticised. The supposed ‘historic claim’ to the city which Polish intellectuals were compelled to resurrect is summarily dismissed – the taking of bricks from intact or only slightly damaged historic monuments to rebuild Warsaw is a tacit acknowledgment of the weakness of that case. Above all, the chapter captures the crumminess of Communist Wroclaw and the sense of alienation which sapped the spirits of settlers who had been deported from historically Polish – and in their view more attractive – areas further east, and dumped in a ruin where ‘even the stones spoke German.’ The happy ending comes as a relief. Throughout the 1980s an increasingly confident and rooted generation of Vratislavian dissidents took on the regime until Communism fell and urban renewal began. This came too late for many, however. Returning to the city after the collapse of the Soviet Empire, I asked what had become of Schiller. I was told that, having lived in Breslau/ Wroclaw all his life, he had ‘gone back’ to Germany.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.