child sprung from us both – showing us our ideal, the way

– to us! father and mother who in sad existence survive him, like the two

extremes – ill-matched in him and sundered from each other – whence his

death – abolishing this little child ‘self’

sick in the springtime dead in the autumn

– it’s the sun

the wave idea the cough

2)

son reabsorbed not gone

it is him – or his brother

I told him this two brothers –

forced back remaining in the womb – sure of myself

century will not pass by

just to instruct me.

fury against the formless

*

did not know mother, and son did not know me! –

– image of myself other than myself carried off in death! –

*

your future which has taken refuge in me becomes my purity through life,

which I shall not touch –

*

there is a time in Existence when we will find each other again,

if not a place –

– and if you doubt that the world will be the witness,

supposing I live to be old enough –

*

father who born in a bad time – had prepared for son –

a sublime task –

the double one to fulfil – he fulfilled his – pain challenges him to sacrifice

himself to who is no more – will it triumph over strength (the man he did not

become) and will he do the child’s task

* * *

end of I

– o terror he is dead! –

– he is . . . dead (absolutely – i.e. stricken

mother sees him thus

in such a way that, sick, he seems to come back – or to see himself again in

the future – obtained in the present

mother I

no one can die with such eyes etc –

father lets out in his terror, sobs ‘he is dead’

– and it is in the wake of that cry, that II the child sits up in his bed – looks

around etc –

and III perhaps nothing – about death and simply implied – in

the space of ‘he is dead’ of I II

The father searches – and stops – the child being there, still, as if to take

hold of life again – hence interruption in the father – and the mother

appearing hopes cares – the double side man woman – first with the one,

then the other, hence deep union

and you his sister, you who one day – (this gulf open since his death and

which will follow us to ours – when we have gone down your mother and I)

must one day reunite all three of us in your thought, your memory

– just as in a single tomb

you who, in due time, will come upon this tomb, not made for you –

*

Sun down and wind

gold gone, and wind of nothing blowing (here, the modern nothingness)?

tears, flow of lucidity, the dead one is seen again through –

*

Death – whispers softly – I am no one – I do not even know myself (for dead do not know that they are dead –, nor even that they are dying – for children

at least – or heroes – sudden deaths – for otherwise my beauty is made up

of last moments – lucidity, beauty face – of what would be me, without me –

for as soon as I am – (that one dies) I cease to be – thus made of forebodings,

of intuitions, supreme shudders – I am not – (except in ideal state) – and for

the others, tears mourning etc – and it is my shadow ignorant of me, that

clothes the others in mourning –

*

although poem based on facts always – must only take

general facts – it occurs here that guiding principle of whole often fits

with the last moments of the lovely child –

thus father – seeing he must be dead – mother, supreme illusion etc.

death – purification image in us purified by tears –

and before image also –

it remains simply not to touch – but speak to each other –

* * *

Dead

there are only consolations, thoughts – balm but what is done

is done – we cannot go back on the absolute contained in

death –

– and yet to show that if, with life gone, happiness of being together etc –

this consolation in its turn has its foundation – its grounds – absolute –

in the fact that (if for instance we want a dead being to live in us,

thought – it is their being, their thought in effect – what is best in

them that comes, by our love and the care we take in being them –

(being, being only moral and taking place in thought) there is here

a magnificent beyond which rediscovers its truth – all the more

beautiful and pure as the absolute rupture of death – little by little

become as illusory as it is absolute (whence we are allowed to seem

to forget the pain etc –) – like the illusion of survival in us, becomes

the absolute illusory – (in both cases there is unreality) has been

terrible and real –

the father alone the mother alone – hiding from each other and this

leaves them . . . together

* * *

Oh! you know that if I consent to live – to seem to forget you –

it is to feed my pain – and so that this seeming forgetting

may spring forth more painfully in tears, at a given moment,

in the midst of this life, when you appear to me in it

*

time – that body takes to obliterate itself in earth – (to merge

little by little with neutral earth on the vast horizons)

it is then that he lets go of the pure spirit which we were –

and which was bound up with him, organised – which can,

pure take refuge in us, reign in us, survivors (or in absolute

purity, on which time pivots and remakes itself – (formerly God)

the most divine state –

*

I who know it for him carry a dreadful secret!

father – he, too much a child for such things

I know it, this is how his being is perpetuated –

I can feel him in me wanting – if not lost life, at least the equivalent –

death – where we are stripped of body – in those who remain

*

and so III

speak to him like this

Friend, you triumph do you not free from all of life’s weight – from the old

sickness of living (oh! I feel you so strongly) and that you are certainly

always with us, father, mother,

– but free, eternal child, and everywhere at once –

and the defeats – I can say this because I am keeping all my pain for us –

– the pain of not being – which you know nothing of – and which I

take upon myself (cloistered, moreover, away from the life to which

you bring me (having opened for us a world of death) –

*

the spiritual burial

– father mother

Oh do not hide him yet etc –

friendly earth wait – the holy act, of hiding him

– let the other mother – common to all men – (into which goes the bed –

where he is now) take him – let the men who have appeared – oh!

the the men – these men (undertakers – or friends?) carry him off

followed by tears – etc – towards earth mother of all mother of all –

his now and (since she is already part of you, your tomb dug by him?-)

he become little man – sombre man’s face

*

death’s accomplices

it is during the sickness – me thinking mother – ? and knowing

In October 1879, Mallarmé’s eight-year-old son, Anatole, died after several months of illness. The child dips in and out of his father’s letters, at times alive and well, demanding, turbulent both in and out of the womb, and at times sick, quiet, withdrawn. Mallarmé’s letters provide a great deal of information about the development of his poems, but tell us nothing of the 210 sheets of pencilled notes towards a poem about the death of Anatole. These notes did not appear during Mallarmé’s lifetime, and when they were first published in 1961 by Jean-Pierre Richard, under the title Pour un Tombeau d’Anatole, they revealed a largely unknown side of Mallarmé, one which even now disturbs the idea of him as the poet of pristine impersonality and detachment. My translation here is based on Bertrand Marchal’s 1998 Pléiade edition of Mallarmé’s Oeuvres complètes.

These notes provide a clear indication of the reason Anatole’s tombeau – unlike Verlaine’s, unlike Poe’s, unlike Baudelaire’s – could not be written. Two impulses are at odds: the father mourns the life and fights the death of his son, while the poet, ‘complicit’ with illness and death, prepares to write the tombeau. These notes show how these conflicting imperatives make the poet’s work suspect and taint the father’s mourning. Mallarmé’s mother had died when he was seven, and his sister Maria when he was 15. Seeing his son precede him into the grave, a dreadful reversal of the natural order, seemed part of a protracted, transgenerational catastrophe: he had lost his mother, his sibling and now his son. As he writes in this prospective tombeau: he ‘did not know mother, and son did not know me! – image of myself other than myself carried off in death!’ His daughter, Geneviève, remembered her father once saying that it had been easier for Victor Hugo, since he was at least able to write about his daughter’s death: ‘Hugo . . . is fortunate to have been able to speak, for me it is impossible.’

Mallarmé is a poet associated with silence, though rarely with the silence of unwritable grief. The most striking thing about these notes is the effort expended in the intellectual and emotional search for a position from which to begin writing. In these notes Mallarmé confronts the things that stop poetry being written: the child’s death is fiercely resistant to being poeticised, even by a poet whose other poems of death are masterpieces of imagined resurrections, new lives, afterlives and defiances of mortality. In the tombeaux written for fellow poets Mallarmé attempted to reconfigure death as a transient, flickering moment of betweenness. ‘As into Himself at last eternity changes him,’ he had written of Poe, imagining the poet’s death as a rite of passage on the way to Becoming. But with Anatole there is no margin for consolation: he has been taken, too young to make his mark on the world and too soon to become a poet and, as Mallarmé imagines, ‘continue father’s work’. Although one sheet of notes reads ‘change of mode of being that is all’, Mallarmé remained incapable of making poetic sense of the boy’s death.

The poet who sought the ‘Orphic explanation of the world’ expresses in these pages his ‘fury against the formless’. Mallarmé sought a reader with ‘a mind open to multiple comprehension’, and it is one of the many paradoxes of his work that it should promise both dazzling feats of abolition and an equally dazzling proliferation of meanings. ‘To name an object is to eliminate three-quarters of a poem’s pleasure . . . to suggest it, this is the dream,’ he wrote, and this dictum has come to stand for many of the ambitions and achievements of French Symbolism. Yet, unlike many of his Symbolist contemporaries, Mallarmé was not a poet of vagueness, of half-tones and pastel shades (like Verlaine), or of the intermittently perceived, imprecisely expressed (like Maeterlinck, whose theatre of silence he was among the first to call attention to). Mallarmé is on the contrary relentlessly and unnervingly assertive. In any stanza of his poetry or paragraph of his prose, meanings are generated and juggled and cast aside, clauses and subclauses, themes and motifs are broached only to be stretched and intercalated and spliced, all unfolding at different speeds and moving in different directions. It is the poetry of the undecidable, not poetry for the indecisive.

With Mallarmé, the blank page isn’t a neutral backdrop. This is most evident in his last great experimental poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance), where the page teems with promise and energy, but at the same time threatens the blankness of cancellation, seemingly poised to engulf the writing that so precariously occupies it. There are few Mallarmé poems that do not draw form from absence and negativity; the first word of the first poem of his Poésies (the ambiguous greeting-cum-leavetaking ‘Salut’) is ‘Rien’. Mallarmé knew that the act of composition must extend into the blankness that surrounds and threatens all acts of the mind, from which they spring, and to which they return. As he wrote in the preface to A Throw of the Dice: ‘the paper intervenes.’

This poem was to have been both the child’s tombeau and his ‘continuation’, a laying to rest and a site of rebirth. Mallarmé uses such words as ‘reabsorption’, ‘continuation’, ‘transfusion’ in an attempt to write Anatole’s death into a ‘change of mode of being’. The boy’s death was to have been seen as a crossing of what Mallarmé described in his tombeau of Verlaine as the ‘shallow stream’ (‘peu profond ruisseau’) of death. Structurally, too, the constituent sections of the poem would have been connected by chronological arches, time-defying bridges across past and present, but also across generations and epochs. More ambitiously even, it would have connected the world of spirit with the world of matter. Yet it proved impossible for Mallarmé to write this poem, partly perhaps because, ranged against the vocabulary of continuity, resolution and restitution, is the insistence of words denoting rupture, crisis and loss. For every projected cohesion – between life and death, father and son, mother and father, past and present, matter and spirit – there is also a terminal chasm which cannot be imagined away.

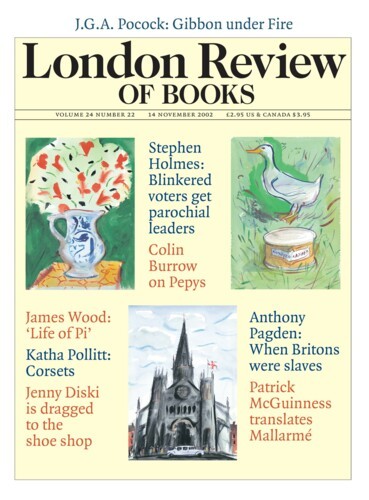

Patrick McGuinness

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.