At the age of 86 and with a broken hip, the Marchesa Casa-Maury was interviewed by Caroline Blackwood for her book about the last dreadful days – months, years rather – of the Duchess of Windsor. The Marchesa had been the Duke’s mistress for fifteen years when Wallis Simpson arrived on the scene. Blackwood explained to the old lady how the Duchess was being sequestered in Paris by her lawyer, Maître Suzanne Blum, who was obsessed with her, and that she was officiously being kept alive, although rumoured to be comatose, to have turned black and to have shrivelled to the size of a doll. The ancient Marchesa began shaking with laughter and continued until tears ran down her cheeks. She managed to pull herself together, but as Blackwood was leaving, started to laugh again as she tried to apologise for her behaviour.

I really shouldn’t find it so funny. It’s awful of me to laugh about it. Do you promise you didn’t invent it all? There’s something so comic about the situation. It’s the idea of that horrible old lady being locked up by another horrible old lady.

Blackwood prefaces the book with an author’s note that is perhaps something more than an attempt at a legal disclaimer: ‘The Last of the Duchess is not intended to be read as a straight biographical work. It is an entertainment, an examination of the fatal effects of myth, a dark fairytale.’ All the old ladies were long dead by the time the book saw the light of day, and Caroline Blackwood, though not so very old a lady at 63, was physically wrecked by booze and in fact had only a year to live, so who knows if one horrible old lady really shrieked with laughter about the fate of all the other horrible old ladies? What is certain is that malevolence is in the air.

Most of Blackwood’s fictions or near-fictions are dark fairytales. There are wicked stepmothers, doomed children, malicious harridans, knights in shining wheelchairs and none of them is alive enough to drown out the cackling of their creator: Lady Caroline the baleful. Isherwood met her in Hollywood in the mid-1950s. ‘Caroline was dull, too; because she is only capable of thinking negatively. Confronted by a phenomenon, she asks herself: what is wrong with it?’ ‘Negatively’ easily turned into luridly. ‘If you sat in a car with her, and you were driving, and she was a passenger, at every crossroad she saw someone being run over and being mangled,’ her friend Xandra Hardie recalls. ‘Almost every minute of her life she saw an appalling disaster happening right in front of her eyes . . . that’s the line of somebody who’s involved with alcohol.’ Or perhaps why someone gets involved with alcohol in the first place.

All this makes her prime biographical material. Elemental (not to say, elementary) fictions written by a Guinness heiress with a title from the Anglo-Irish aristocracy give her biographer no end of clues to a wayward, drink-sodden, chaos-creating life. And the disordered, self and other-destructive life offers all manner of interpretations of the fiction. Nancy Schoenberger is not interested in literary criticism; Blackwood’s books are discussed entirely with reference to the life. To do this is to demean a writer, I would have thought, but perhaps Caroline Blackwood’s life-in-its-time is of more interest than her work. These days biography sells, and we may be moving to a point where fiction is seen to be no more than a useful biographical resource.

Blackwood’s Lady-Carolineness, her unhappy childhood, busy sex life, connections to major figures in art and literature, and gaudy drinking does make her a toothsome subject. As she must have realised. Schoenberger was suggested to Blackwood, by then living on Long Island, when she said she was looking for a biographer. They spoke on the phone, but Blackwood went into hospital for a cancer operation the day Schoenberger arrived in Sag Harbor, and died in New York two weeks later, so they never met. As a result, apart from assistance from Blackwood’s sister, Perdita, Schoenberger found herself writing an ‘opposed biography’, as the adult children eventually refused to co-operate. All grist to the mill. ‘Once I got to know Caroline better, I understood why.’ Blackwood’s witchiness is dangled at the reader before the book starts, in the acknowledgments. The biographer began to feel haunted by her subject (don’t they all?) and when Schoenberger had a car accident just after a visit to Blackwood’s daughter Evgenia, Evgenia remarks: ‘I bet you were thinking about my mother when you hit that car.’ Making a surprise visit to Lady Maureen Dufferin, Blackwood’s mother, she bends to pick up a scrap of paper from the front step. It reads: ‘Just remember I am a witch.’ Ooh-er.

John Huston referred to the three Guinness girls, of whom Maureen was one, as ‘lovely witches’. To say that someone was brought up as a wealthy, landed aristocrat (moneyed, narcissistic mother; aristocratic, fey father) is tantamount to saying they had a deprived childhood. To have a rich, deprived childhood is probably no better than having an impoverished one; at any rate it’s arguable. The Blackwood children (Caroline, Perdita and Sheridan) were half-starved, beaten and neglected by a series of vicious nannies. Still, there was scope for narrative and adventure. They had each other, and like babes in the wood, they were given titbits to eat by their Irish tenants, who felt sorry for them. Like children in an Arthur Ransome or C.S. Lewis novel, they rambled unnoticed around the great house and were given to taking off on their bicycles up the main road to the nearby town.

It is well known in the world of fairytale and post-Freudian analysis that it is not a good thing for a child to have a wicked witch, especially a lovely wicked witch, as a mother. It is also probably not a good thing, in the world of getting on with your life, if you happen to have such a parent and are eager to perceive yourself as doomed by story and psychoanalytic theory – and both Blackwood and her biographer see her as doomed by her beginnings. Becoming what she did it was clear, if somewhat teleological, that she could not have been anything else. Having a self-regarding, unaffectionate mother makes it perfectly understandable that Blackwood would leave her oldest daughter, Natalya, aged 15, alone in their London flat without any money. (She was trying to get away from her third husband, Robert Lowell, who was mad at the time.) It is taken as inevitable that patterns are inevitably repeated. Blackwood becomes a lifelong drunk given to hysterical and unsuccessful relationships, and it is no surprise that Natalya dies of a heroin overdose at the age of 17. Blackwood is acknowledged even by her friends as having some responsibility for this, not least because two years before she had published The Stepdaughter, which has in it a savage portrait of a fat, unhappy, dim-witted and doomed adolescent whom everyone saw as the less-than-loved Natalya. Ivana, aged six, suffered third-degree burns when she tripped on the lead of a kettle of boiling water, and friends thought the chaotic house and Blackwood’s drunken neglect had something to do with the accident. Schoenberger tries to smooth out the general judgment. ‘Caroline would always acknowledge how important her children were to her, but her ability to look after them was becoming increasingly impaired.’ The blame is muted, because, in retrospect, what else could possibly have happened? If you were not loved and taken care of then you can’t be expected to care for and love other people, except destructively. This is now the unquestioned basis for most biography. Strange that the generation who decided that they would not be dominated by biology should have so completely accepted their psychoanalytically prophesied destiny.

In fact, Schoenberger doesn’t make very much of Blackwood’s conformity with her times, though it was frightfully fashionable in the early 1950s for the upper classes to mingle with louche artistic types – and, of course, vice versa. She met Lucian Freud at a party given by Lady Rothermere. He was the beautiful untidy young man standing at the back next to Francis Bacon and booing loudly while everyone else clapped Princess Margaret’s execrable rendering of a Cole Porter medley. Here, nicely arrayed, are the components of the bohemian life of that period. Scruffy, wild and very good-looking artists (geniuses only – and no harm if they come with very famous grandfathers) drank and pranked as licensed fools among the aristocracy who included them on their party lists and popped into the Gargoyle and Colony Clubs with them in search of a little edge. Few of the Soho mob could have been more satisfactory than Freud, dismissive and yet a devout social climber attendant on his upper-class sponsors. He munched a bouquet of purple orchids, but, in spite of her voice, ‘accompanied Princess Margaret to nightclubs wearing saffron socks’ (Freud, I think), and put up with the ingrained anti-semitism of his chosen milieu. Evelyn Waugh called him that ‘terrible Yid . . . a jewish [sic] hanger-on . . . called “Freud”’ with ‘very long black side-whiskers and a thin nose’. Well obviously, Caroline was going to marry the man: she was wealthy (her unloving mother had settled the astonishingly large sum of £17,030 a year on each of her children in 1949) and she was angry. And of course the man was going to divorce his wife and marry Lady Caroline. Soho life was very seductive for a poor little rich girl who was also very beautiful. Her lovers included all the right intellectuals, and there were degree courses to be had in drinking yourself stupid at the Soho academies in Dean Street and Old Compton Street. To be accepted by Muriel at the Colony Club and Gaston at the French Pub added kudos to the twilit and self-conscious life of a Soho drunk. Self-image was no less important then than it is now. In Rome she found the men who hung about her unacceptable, except for one who stroked her bare arms and said ‘Morbida’, which means ‘soft’. A former lover, the screenwriter Ivan Moffat, explains: ‘She couldn’t speak Italian, really. So she thought, “Ah, here’s a man who knows what he’s talking about,” so she invited him up . . . it wasn’t until the next day that she came to know what he meant.’ Moffat tells this, as Blackwood must have told him, as a joke. ‘A very disillusioning story – but funny! It told me a lot about Caroline Blackwood.’ Schoenberger intones, more solemnly, that it ‘revealed to him an essential aspect of her nature’. She was also conscious of her origins and never let go of being Lady Caroline. According to Ian Hamilton, ‘she had a kind of aristocratic sense of entitlement and was capable of great vindictiveness when she didn’t get what she wanted.’

Not only was she beautiful, smart and a Lady, but she could fund the arts – or at any rate her chosen artists. She bought houses in London and the country for her brilliant but broke husbands. Between inspiring and housing Lucian Freud (Caroline is Girl on a Bed) and Robert Lowell (Caroline is The Dolphin) she married Israel Citkowitz, a composer considered by Aaron Copland to be a genius, and the father of Evgenia and Natalya (Ivana, as her name might have suggested to anyone paying attention, later turned out to be Ivan Moffat’s daughter); Sheridan is Lowell’s son. Citkowitz had already given up composing, being too clever or lazy or something, and became Blackwood’s house husband, doing the childcare, cleaning up, shopping and cooking. This was fortunate because Blackwood was epically undomesticated and usually too drunk to notice that the cigarette butts she threw on the floor were still alight. Citkowitz continued in this role after Blackwood married Lowell, living on the middle floor of the London house, taking care of the children who resided on the ground floor, along with a series of passing nannies and au pairs. Lowell and Blackwood had the top flat in which to be mad, bad and dangerous to know to their heart’s discontent.

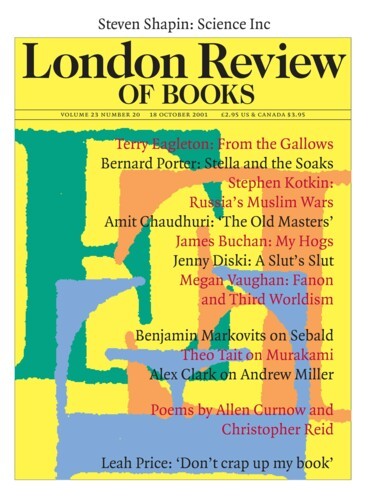

Like a proper upper-class girl, Blackwood was a slut’s slut. She is variously described by those who knew her as filthy, unwashed, careless with her hygiene, stinking, and it took no more than a few days for her to reduce a room to a fearsome slum. Lowell’s friends describe a visit to their New York apartment: ‘The squalor was unbelievable. There were bloody sanitary napkins on the floor; cigarette butts, bottles of liquor, and empty pill-boxes were scattered around the room. It looked like the room of an addict.’ Towards the end of her life Blackwood visited Steven Aronson in a borrowed house on Long Island. Aronson placed buckets of water all along the corridor leading to her room for fear that her cigarette ends would start a fire. After she left, the maid went into the room Blackwood had occupied and ‘backed right out’. ‘Mr Aronson,’ she said, ‘don’t go in there.’ Empty pill bottles and vodka bottles were strewn all over the floor, and there was ‘an acrid, all-too-identifiable odour’. Aronson learned later from a friend in the industry that Caroline ‘was on a list that hoteliers keep of undesirable guests’. How else is a rich, upper-class rebel to behave? Perdita took to breeding horses and running a charitable riding school for disabled children, Sheridan inherited the grand house, married amiably and died of Aids. Someone had to be Caroline.

What makes Blackwood more than just good biography bait is that, in addition to the grand guignol life, there is the work. She was a serious alcoholic but she took Bacon as her model when it came to productivity. She might down a couple of bottles of vodka a day, but once the marriage to Lowell was over, she wrote doggedly most mornings and produced a decent body of work in a short period, fiction and non-fiction. As Schoenberger says, she was not content to be a beautiful muse. Really, the time for muses was past. By the 1950s beautiful women either drank themselves to death or finally got round to doing some work. And the work is at the very least interesting, even if not, as the press handout bizarrely suggests, comparable to that of Edna O’Brien, Iris Murdoch, Muriel Spark and Samuel Beckett (though I wish just for the sake of the gaiety of the nation that someone’s work was comparable with all those writers).

The writing strains towards being very good, but is sabotaged by fear. Blackwood’s friends are agreed that she saw only the bleakest, most negative aspects of the world and the people in it, and it is surely from that place in her that she writes. According to Barbara Skelton, ‘on hearing of someone’s ghastly misfortune,’ Blackwood ‘would double up laughing’. She maintains the coldest eye she can manage, shying away from sentimentality as if it were death itself. Death, indeed, seems to be preferable. The cruelty of the stepmother in her first novel is virtually unrelieved, apart from a moment of faint decency that is immediately rendered irrelevant by the disappearance and probable death of the stepdaughter. The characters in the very similar stories published as Good Night Sweet Ladies share cosmic self-centredness and while they might discomfort others, they see very little beyond their own troubles. The reader is not offered anyone or anything to like, the bleakness of the vision is everything, even in the spuriously upbeat ending of Corrigan, where the con artist turns out to have made a sad old woman very happy in her last months by permitting her to live an illusion. The novels are strange and intriguing, but they are also slight, because for all their capacity to look into the void, they shed no light on it. They describe pathologies of varying degrees, give no quarter, lack any generosity; finally you say: ‘so what?’ They are indeed dark fairytales, and they have the rigidity of fairytales. Sentimentality is a very bad thing in a writer, but simply to deny its existence is to avoid one of life’s central textures. The fear of appearing sentimental in the end condemns the work to smallness. Even the laughing old Marchesa stopped for a moment between cackles:

‘Love affairs . . . They don’t really matter in the end. They seem so important at the time. But in the end they don’t matter . . . I wonder what does matter in the end.’ She seemed bewildered. ‘Family, I suppose . . . I had all my grandchildren around here the other day.’ Her face lit up. ‘It was amazing to find oneself head of such a large, lovely clan.’

If Blackwood could have hit on something that mattered, her work might have loomed larger than her biography.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.