At Christmas 1859, one of the 19th century’s most celebrated headmasters suddenly, and for no obvious reason, resigned his job. The Rev. Charles Vaughan had taken charge at Harrow in 1845, when the school was close to collapse. There were just 69 boys on the roll (many of whom were seriously in debt to the local loan shark); even by Victorian standards the boys’ lodgings were a health hazard, with not even a bathtub between them, still less a bathroom; the headmaster’s house had burned down the year before, thanks to a fault in the new heating system ingeniously, but incompetently, improvised by the maths master. In less than fifteen years, Vaughan – who had been a favourite pupil of Thomas Arnold at Rugby – transformed the school, spiritually, sanitarily and commercially. He raised money for a fashionable chapel by George Gilbert Scott as well as new boarding houses, decently appointed and, from the mid-1850s, complete with water closets. He promoted an Arnoldian style of religious and moral education, centred on his own weekly sermon. And most important of all, for ultimately it was pupils’ fees that underwrote the costs of the revolution, he attracted Harrow’s old customers back: at one point during his reign there were 488 boys in the school. The success made Vaughan himself wealthy. A large proportion of what the boys paid went directly to the Head. By the late 1850s, his gross takings (before paying his assistant staff) were somewhere between £10,000 and £12,000 – making him, as Christopher Tyerman calculates, ‘the equivalent of a modern millionaire’.

In 1859 he might have expected to move on to the mastership of an Oxbridge college (the fellows of Trinity, Cambridge are said to have been already trembling at the uncomfortable prospect of this new broom) or a fashionable bishopric. People thought of him as a future Archbishop of Canterbury. Instead, he resigned from Harrow with almost no warning at all, and in 1860 took a decidedly unglamorous living as vicar of Doncaster. The highest he was to reach in the Church was Dean of Llandaff. The secret of his puzzling resignation probably lies in a story told in the memoirs of John Addington Symonds, a pupil at Harrow at that time, which were not published till the 1960s. There, a simple tale of blackmail is revealed. For all Vaughan’s intense sermonising on the evils of homosexuality (in one purple passage he referred to a pederast as ‘a murderer in the worst of ways; a murderer of the soul’), he had been having an affair, largely conducted in the Head Master’s office, with one of the Upper Sixth. Symonds later informed his father, and Symonds père threatened Vaughan with exposure unless he resigned.

In his History of Harrow School, Tyerman is carefully unsensational about this scandal. He points to inconsistencies in the account offered by Symonds’s memoirs and to their underlying agenda: not a documentary narrative but ‘an extended propagandist essay on the nature of homosexual orientation and Symonds’s heroic passage to enlightenment’. Nonetheless, he has unearthed some corroborating evidence – including a steamy letter to another young favourite, apparently written while Vaughan was invigilating a school exam – and concludes that the story is broadly true. But this characteristic piece of English hypocrisy is only one element in Tyerman’s demythologising of the school’s ‘greatest Head Master’ (many other ranting homophobes have been found in bed with young boys). He scratches the surface of Vaughan’s extraordinary transformation of the school, his brilliant promotion of Harrow and himself, to hint at an alternative and far less favourable view. Vaughan did no more – and probably less – to reform the curriculum than his disastrous predecessor, Christopher Wordsworth, who had at least introduced maths into the teaching programme. His modish enthusiasm for Arnold’s disciplinarian principles masked a brutish commitment to flogging (he insisted on a new birch each time and liked to leave the birch buds painfully embedded in the wounds) and did little to change the behaviour of the boys: Vaughan’s Harrow appears to have been no less dominated by bullying, drinking and fighting than the notorious school of forty years earlier. The cleverest boys, not to mention the masters, saw through him as a shallow, ignorant, literal-minded man, who (as Tyerman puts it) ‘compensated for his small mind with expansive care for his pupils’.

Vaughan is not the only victim of Tyerman’s unsentimental look at the careers of 28 Harrow Heads, from the first incumbent, William Launce, who took up office at what was then called the Harrow Free Grammar School in 1615, with the vicar’s son as his first pupil, to Ian Beer, the last Head but one, who retired in 1991. A few emerge as hopelessly inadequate to the task of running a school of any type (like the unfortunate Wordsworth, who presided over ‘moderate anarchy’ until the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, came to the rescue of his old school by installing him as a canon of Westminster). But Tyerman suggests that more often than not the governors, staff and boys (or some combination of the three) were glad to see the back of any incumbent Head, even those now acclaimed as heroes in the Harrovian pantheon. Montagu Butler, for example, Head from 1860 to 1885, started with flair and helped to invent many of the traditions that became crucial to the school’s image of itself, notably the cloyingly sentimental school songs and the cult of sport. But in the end even he was eased out and pushed into accepting the Deanery of Gloucester: his performance had become increasingly erratic and, given that he was only 50, the governors feared ‘an endless Headship’. (Happily for him, the mastership of Trinity, Cambridge followed in 1886, and soon a rejuvenating new wife less than half his age.) Similarly, Robert Sumner, who held office in the late 18th century and was hailed at the time as ‘the best schoolmaster in England’, seems to have died before he was pushed. And even Dr Drury, the charismatic and up-market Head eloquently celebrated by Byron, proves to have had a seedier side. He was so keen to maximise his own profits he moved out of his official house to make way for more boarders; the house degenerated into such a foul slum that the governors were forced to add a ‘repairing clause’ to the next Head’s contract.

Of course, a history of a school is more than a history of its Heads. But, in focusing much of his narrative on their careers, Tyerman raises important questions about the nature of educational leadership and how we judge it – with implications not just for Harrow, but for any school, of any type, anywhere. What makes a good Head? Are the odds stacked against anyone emerging with unequivocal honour from the competing pressures and demands of governors, parents and pupils? Who decides whether a Head will be damned or deified, written off as incompetent or lauded as an inspiring eccentric? (In the case of Harrow, though it would certainly be different in other schools, Tyerman sees the legions of Old Harrovians as playing a crucial role in forming reputations.) More fundamentally, what impact does a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ Head have on the education a school claims to deliver?

This raises yet wider issues that repeatedly come into view at the margins of Tyerman’s story. What is to count as a good school, and on what criteria? How do you judge if its educational diet has ‘worked’? How do you balance the easily measurable, and instant, ‘performance indicators’, such as skills acquired, exam results or Oxbridge entry, against what really counts – namely, what a pupil does with his life – but is only visible decades later? To take the obvious example, was Winston Churchill, who flunked his Latin and was demoted to the so-called Army Class, one of Harrow’s failures or its greatest success? Time and again Heads at Harrow, as elsewhere, must resort to catchy slogans to generate enthusiasm for the dubious educational experiments (what we call ‘teaching’) being carried out under their aegis. Time and again the slogans come back to haunt them. ‘Treating pupils as people’ sounds admirable – but not, as Vaughan discovered, if you allow them to be sexual people, too.

Tyerman certainly sees a role for a charismatic Head, at least in a school’s popular reputation and its own self-imaging. But outside factors beyond any Head’s control, as well as sheer economics, are almost always more significant in ensuring that a school thrives. More often than not, periods of apparent decline at Harrow, measured crudely by pupil numbers, coincided with periods of decline in the public school system more generally. Christopher Wordsworth may have been an unworldly incompetent, who was said to have breathed ‘the atmosphere of the Council of Nicaea’ rather than Harrow-on-the-Hill, but his ineptness cannot explain why Westminster’s pupil numbers were also plummeting (from 300 in 1821 to 67 twenty years later), as were Shrewsbury’s, Winchester’s and Rugby’s. This widespread crisis of recruitment must have had more to do with pressure on the purses of the middle ranks of the gentry in the early 19th century: when times got (relatively) hard, finding the cash for school fees was not the first priority.

In fact, money was always the bottom line. Tyerman repeatedly makes the point that fee-paying schools are commercial enterprises. The input and contentment of their teachers, the quality of their facilities and the range of teaching and extra-curricular activities on offer, all directly depend on the school’s income; and that income (barring an occasional lucrative property deal or particularly lavish endowment) depends on enough parents being willing to pay. Every group of Harrow governors since the 17th century, and most of its headmasters, have been well aware of the equation between bums on seats, money and a thriving institution. It is not so different for any school, of course, fee-paying or not. A History of Harrow School should be required reading for all government officials who imagine that a ‘failing’ comprehensive can be rescued by a new charismatic Head, with no extra injection of cash.

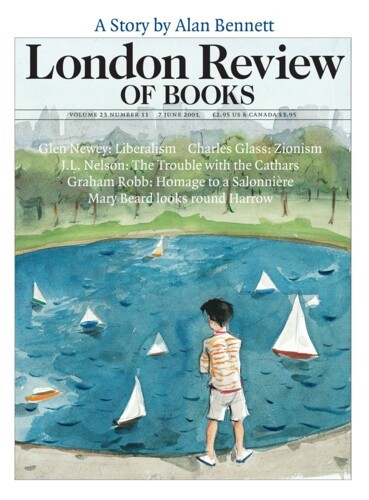

Tyerman himself comes from the heart of Harrow, where he is Senior Tutor. Despite, or maybe because of, this closeness to the institution, his book is no cosy eulogy, on the model of so many public school histories: advertisements in all but name, illustrated by retouched sepia shots of the school’s first fire brigade, the young gentlemen meeting poor boys at their East End ‘mission’, some hilariously posed, and bizarrely clad, rugby teams, and so on. It is very much to Tyerman’s credit, in fact, that his chosen illustrations are so dull (mostly mug-shots of the Heads) and include not a single picture of a cricket match – except for the one blazoned by his publishers on the front cover, misleadingly. For what he offers is a careful, sometimes agreeably acid analysis of four hundred years of English social and educational history, seen through the microcosm of one of the country’s most famous and notorious schools.

Predictably, he is very good on the history of flogging, which came to end at Harrow in 1987, when the last boy in ‘a very long, distinguished and crowded line . . . received his punishment’. Though clearly no admirer, even nostalgically, of the kind of birchings administered by the likes of Vaughan, Tyerman sharply cuts through the clouds of modern disapproval to expose the inconsistencies, the paradoxical mismatch between theory and practice, and the sometimes unexpected consequences of the traditional culture of beating. Why did they do it, he asks, when it so clearly acted as an incentive to disobedience, as much as a deterrent? (Mere sadism can’t be the whole answer.) Did the 19th-century reforms, now largely associated with Arnold’s influence, reduce the amount of gratuitous violence practised in the school, while investing flogging with an intense moral purpose? Or are we dealing here with the fraudulence of so much Victorian reform – no real change, but ‘old habits . . . confirmed through rhetorical transformation into noble, improving traditions’?

In Tyerman’s hands, the Head Master’s ‘Punishment Book’ (where beatings were supposed to be recorded) is a revealing case-study for the sometimes terrifying regime of beating, and for the tensions and ambivalence that surrounded it. It is not just that the raw statistics make uncomfortable reading: James Welldon, for example, Head between 1885 and 1898, who claims to have relaxed discipline at the school, averaged a hundred floggings a year, with never fewer than five strokes each (‘If this is relaxation,’ Tyerman remarks, ‘the mayhem under Butler must have been savage indeed’). But by the 20th century the Book itself had become an object of disagreement. In 1935 Paul Vellacott, who presumably continued to beat boys at least for major offences, decided to discontinue entering each punishment in the Book. ‘I decided . . . to discontinue this tale of degradation, ugliness and tears,’ he wrote in it. ‘The picture the foregoing pages give of life in a school, as lived by a Head Master . . . fills me with a sense of shame.’ Less than ten years later, the new Head reversed the policy: ‘I consider the foregoing a sentimental view . . . No corporal punishment should be administered without record kept; and memories are fallible.’ It is hard now to unravel the different ideas and emotions at work here: embarrassment, accountability, accurate record-keeping, the pornography of the written word. But it is clear enough that, as Harrow’s tradition of beating drew to a close, the ethics of writing (as well as of practice) entered the controversy.

Tyerman casts his eye equally effectively on other, sometimes awkward aspects of Harrow’s history. His story of low-level, endemic racism and anti-semitism in the school up to the 20th century is occasionally enlivened by a trace of dissent (whether the consequence of liberal ideology or naked self-interest). Those masters, for example, who were committed to a spirit of co-operation and harmony between the aristocracies of the British Empire were keen to attract the sons of the (native) colonial elites. But how should this be done? In 1890, the Head Master, unsuccessfully, proposed a designated Muslim house under a Muslim housemaster. In practice, until the 1920s, non-whites mostly boarded privately with the maths master; though one eccentric housemaster in the late 19th century, Reginald Bosworth-Smith, consciously set out to turn his house, the Knoll, into a microcosm of Empire. The boys’ joke was that the only language mutually comprehensible at the Knoll was Esperanto; masters spoke more coyly of its cosmopolitan ‘tincture’. Similar debates surrounded the admission of Jews. In their case a separate house was up and running by the 1880s, though it closed in 1903. Official anti-semitism was soon balanced by the school’s desire to tap the Rothschilds for money.

Even more piquant, given current political debates, are the centuries of arguments about the role of the Free Scholars within a largely fee-paying school. The original foundation had provided for the education of local boys at no charge, alongside fee-paying ‘foreigners’. One of the main themes of Harrovian history (it was the same at Rugby, Shrewsbury and elsewhere) is the growing dominance of the fee-payers at the expense of the intended recipients of the founder’s charity. In the first decade of the 19th century the locals complained of being cheated of their educational rights and took the school to court – unsuccessfully. For years, only a tiny proportion of locals who applied for a place were admitted (blatant snobbery being justified by the – now uncheckable – excuse that very few of them could even read). By the 1830s, Free Scholars were still causing a problem, but for quite different reasons: there were now too many of them. It had not escaped the notice of certain sections of the elite that if you moved, even temporarily, to the Harrow catchment area you could ask to have your son educated at the school for free – as a poor local boy. It is a situation strikingly reminiscent of the middle-class manipulation of the Assisted Places scheme a hundred and fifty years later, or of their continuing rush to buy up houses close to good state schools.

Tyerman’s History is grounded in immensely detailed study of the school archives, the governors’ minutes, the Head Master’s and staff files. It is a considerable tribute to the openness, or maybe the self-confidence, of the school authorities that they were prepared to let so many skeletons out of the cupboard, even comparatively recent ones. (If they have kept anything under wraps, one dreads to think what it might be.) Inevitably, this institutional focus colours Tyerman’s narrative and the style of his analysis; acute as it is, his stress on the primary role of economics in the history and development of the school can hardly be unrelated to the preoccupations of the governors themselves, in whose minute books he has been immersed. Inevitably, too, though he has trawled widely in the school’s memorabilia, his History fails to answer the tantalising question of what it was all like for the boys. This is the black hole at the centre of every school history; and, in an important sense, the question is unanswerable. On the one hand, accounts of the school experience are always retrospective, already formed by the myths and anecdotal traditions of which they will become a part, by definition a commentary on the vicissitudes of adult life as much as a dispassionate narrative of childhood. On the other, the documents from the classroom itself, the timetables, exercises, marks, even the routinised letters home and stereotyped diaries, are difficult to convert into empathetic understanding.

This is precisely the point raised in the introduction to Arnold Lunn’s novel, The Harrovians. Lunn had been at Harrow between 1902 and 1907 (in Bosworth-Smith’s old house, speaking Esperanto, no doubt, with the ‘dusky potentates’ who still remained); he was the son of the founder of the travel agents and went on to Balliol and then a wholesome career, in which he became best known for inventing the slalom. The publication of his novel in 1913 caused, in Tyerman’s words, ‘widespread outrage and indignation, Lunn being forced to resign from his five London clubs’. (Lunn’s own memoirs are rather more low-key about the affair.) The Harrovians is not an overt denunciation of the school. The cause of the trouble was Lunn’s unflamboyantly documentary style: a frankly unengrossing plot is set against a day to day background of anti-intellectualism, bullying, absurd rituals, snobbery, the tyranny of sport but, most of all, sheer boredom (‘Life for the average Harrovian is monotonously uneventful and happy’). Lunn’s pitch is his realism. ‘You and I,’ he writes in the introduction, ‘have often come out of Chapel or Speech Room wondering whether the distinguished visitors, who spoke with such bland assurance of our most intimate sentiments, had really been boys themselves’: his own book is an ‘effort to recapture the rough sincerity of Harrow life before we, too, forget’ – and is based, he claims, on diaries he kept as a boy.

The impression of daily life at school given by The Harrovians is certainly different from the high-octane sentiments of such classic Harrow stories as H.A. Vachell’s The Hill: A Romance of Friendship (21 editions between 1905 and 1913). In fact, Lunn neatly parodies The Hill’s climactic scene at Lord’s, where the Prime Minister’s son snatches victory from defeat at the hands of Eton in front of his proud Papa (but only just – ‘things may look black in South Africa,’ the story assures us, ‘but they’re looking blacker in St John’s Wood’). Quite how accurate Lunn’s account is, we cannot know. Indeed, three years at Balliol may not have given the book the thick retrospective gloss applied in novels or memoirs written from retirement; but it is a retrospective story even so, whether or not it is based on contemporary diaries. All the same, the combination of Lunn’s picture of monotonous philistinism and Tyerman’s clever, engaging, sometimes subversive history offers about the best picture you could get of Harrow in the early 20th century.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.