Jason Brown’s sometimes excellent first book is a collection of stories mostly set in and around Portland, Maine. His subject is what Sherwood Anderson, a pioneer of the genre, called the ‘buried lives’ of individuals. His narrators – loners, neglected children, thieves, substance abusers – are isolated, unsuccessful people, longing, more or less consciously, for some kind of wider community. Despite the small scale and determinedly regional focus of his fiction, Brown’s vision – like Anderson’s – is grand, even grandiose. It’s a way of imagining a huge, fluid industrial society.

Among Anderson’s articles of faith was the need to reject the ‘poison plot’ – one of the standardised formulae that dominated the short fiction market of his time – in favour of more organic narratives, as suggested by careful observation. Brown seems aware that realism, if it is to work, must engage in the ongoing struggle between life and the devices used to frame it; with considerable intelligence and invention, he constructs narratives that appropriately shape, manipulate and interpret their subject matter. Nevertheless, this collection indicates a gifted writer whose ambitions are limited by contemporary versions of the ‘poison plot’.

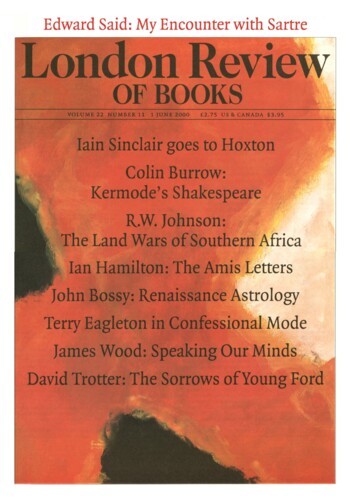

The words ‘Driving the Heart’, reinforced by an ominous cover photo showing a bleak highway at dusk, suggest a dark, earnest and intensely metaphorical tale. So it’s something of a relief when Brown jolts this expectation. The narrator of the title story is a man who couriers body parts from organ donors to the critically ill; in this case he’s taking a heart to Lebanon Springs, his old hometown. There’s a kind of gallows humour at work here which makes it much easier to stomach the story when, thereafter, it does become dark, earnest and intensely metaphorical. But many aspects of the story are less than surprising. The driver turns out to be a reformed alcoholic, living between depression and despair after a wild past; he describes a featureless semi-urban sprawl in hard-edged, neutral sentences, often in the present tense: ‘I live in a so-so neighbourhood. The people there smell and never take out the trash. I look out my window at a funeral home.’ By the end of the second page – as is the case in so many American short stories – the long shadow of Raymond Carver has fallen unmistakably over the narrative.

The narrator describes his unusual line of work and various grotesque experiences from his past in an apparently straightforward style. For example, he was once in a car crash caused by a deer on the road that left the driver dead or at least unconscious, his head resting against the steering wheel; the narrator, who was sitting in the backseat, deadpans: ‘The deer stood in front of the car watching us. Then he closed his eyes. I never made it back to Lebanon that time.’ Interpretation is left to the rhythms of the language, and to the meaning which seeps through the interstices between the statements. As with Carver’s fiction, the smooth surfaces of the story are ruffled or broken in a way that reveals the underlying unease.

This is a well-known style, familiar enough to have inspired various faintly snide classifications – ‘dirty realism’, ‘post-alcoholic blue-collar minimalist hyperrealism’ – but Brown does it well. His opening line – ‘Travelling between Danvers and Natick yesterday I saw a man in a flower truck drive by at 80 mph with his eyes closed’ – has something of the quality of Carver’s ‘A man without hands came to the door to sell me a photograph of my house.’ The linear plot is taut and thought-provoking, subtly and confidently elaborating on what it might mean to drive bits of dead people around (to a very tight schedule). As the driver explains to his co-worker,

‘A man in Abilene, Texas, gets drunk and drives his car through a 7-Eleven. Six hours later his heart sits next to you in a large silver case marked Heart, and we are driving down the highway at the speed limit toward some supine client in a hospital room asleep or possibly in a coma who will not live another day without this heart. This,’ I say to Dale, ‘is the importance of your job.’

The story is well situated between the grim and the humane, the realistic and the metaphorical, the connected and the severed, the bodily and the mechanical.

This is one of three strikingly good stories in the collection; the others are ‘The Coroner’s Report’, about a benumbed coroner and his alcoholic brother, and ‘Detox’, in which an obese woman climbs into an air-vent to escape from the basement of a drying-out facility. Despite some local differences in style, they are all fairly similar, resembling Carver’s more considered stories – like ‘Why don’t you dance?’ or ‘Viewfinder’. Largely, it’s a coarser version of Carver that Brown seems to have arrived at. There’s the same stoic, bewildered sense of humour; the same impression of adversity redeemed by a world-weary dignity; the same feeling, explicitly expressed in ‘Detox’, of ‘two lives, one drunk, the other sober’.

It might seem unfair to pick out these three stories, when Brown does try out several new and distinctive directions elsewhere. He clearly has his own particular concerns – parent-child relationships, for example – and idiosyncrasies, like his interest in animals. (For not entirely obvious reasons, these two seem to run together, as in the creditable last story, ‘The Dog Lover’, in which a father and son discuss the ethics of canine euthanasia, and the less assured ‘Animal Stories’, about a lonely man nursing his dying mother.) There’s also a strain of fabulism running through his work, and quite a few Chekhov-style epiphanies: moments of illumination and insight are obscurely uplifting even when they ought to be depressing. In Brown’s case, the power of these moments is reduced by a tendency to hit the keynotes quite hard, conveying messages already communicated by the logic of the story. When he learns that the patient waiting for the heart has died, the narrator of the title story concludes that ‘there is no way for me to explain how we could have driven all this way with a heart for which, in the end, there is no life.’

It’s possible to overstate Carver’s specific influence. There is a whole group of short story writers who emerged around the same time as him, and who share certain broad similarities: Tobias Wolff, Bobbie Ann Mason and Ann Beattie all use an austere, melancholic naturalism, tinged with the grotesque, that owes something to Anderson’s successors – early Hemingway, Flannery O’Connor, Faulkner. In the 1980s, short fiction established itself as a form appropriate to their subject matter: broken homes, failed marriages, second wives, second chances, missed opportunities and short-term jobs. It exploited the lack of a wider context, the loss of more monolithic frames of meaning (the counterpoint to the paranoid connectedness of the Pynchon/DeLillo school).

While this style was appropriate and often powerful, in Driving the Heart it sometimes feels more like a mannerism. The quirks and innovations Brown introduces don’t conceal the mixture of fatalism and whimsy that seems to have become almost canonical. Some of the more flashy features are impressive – like the breakdown, by category, of US fatality figures in ‘The Coroner’s Report’ – but too often, they seem like forlorn distractions from the fact that he’s trapped in a mode that no longer serves a useful purpose. Short stories have an inbuilt tendency towards stock features and situations; and bits of the collection could be criticised for degenerating into K-Mart chic, acting out various clichés of contemporary Americana. Highways, brand-name humour and fast-food joints are dwelled on; and it’s not much of a surprise when hicks jump out of pick-ups, pulling guns and playing out comic stick-up routines.

Carver’s writing is often powerful because he seems to be describing forms of deprivation that have not yet been properly acknowledged or named – least of all by those suffering from them. Brown’s version of trauma and domestic dysfunction sometimes has a pre-packaged feel to it. (As Karl French pointed out in relation to American Beauty, the term ‘dysfunctional family’ feels almost tautologous nowadays.) Driving the Heart insistently fingers parents as mad, ill, absent or damaging: the focus of resentment and rage. The household is subjected to much metaphorical and real violence: the hero of ‘Thief’ is a house-breaker looking for some kind of missing intimacy in other people’s homes; in ‘Head On’ various low-lives neck vast amounts of pills and booze before smashing their car into an empty house. This sense of being damaged by the family past is in turn projected on a macrocosmic scale in the form of the Vietnam War, which plays an important role in five of the stories. The connection between the personal and the national psyche is made explicit in ‘Halloween’ and ‘The Submariners’, in which distant or disliked fathers die in Vietnam. The more schematic elements are kept from becoming oppressive by the skilful use of detail and a delicate balance between guilt and anger. But Brown’s technique is still disturbingly broad-brush, lacking plausibility and tact. You feel he has already made up his mind about what Vietnam will mean to the characters, and this takes the air out of the stories, making them much less effective than Carver’s sidelong ‘Vitamins’, Mason’s extraordinary ‘Big Bertha’ – in which a veteran is unhealthily fixated on a colossal piece of equipment at the strip mine where he works – or Tim O’Brien’s compelling Vietnam fragments, The Things They Carried.

It may seem unfair to compare a first-time author unfavourably with various well-established names, but it’s also a backhanded compliment. There’s a thin line between being derivative and feeling your way with the help of like-minded precursors; just as it’s sometimes hard to distinguish schematic writing from fiction designed according to an interesting scheme. Brown is obviously a talented writer, but Driving the Heart strays onto the wrong side frustratingly often. It’s hard to fight off the impression that, trapped inside this sombre and occasionally boring book, is a sharper, funnier, more light-hearted view of the world. If he was to have faith in the more trivial details – rather than insisting that they are the real clues to present-day America – the reader’s eye might not slip across the page in the way that it sometimes does.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.